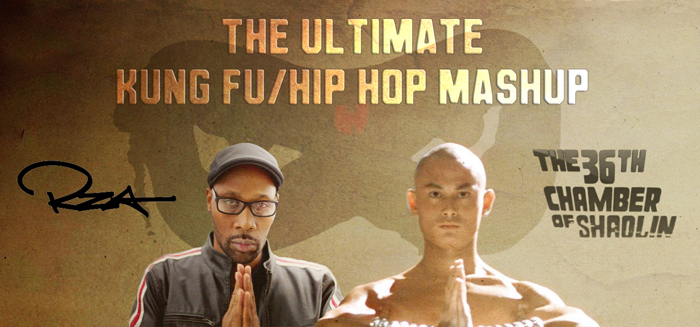

At the Rialto Theatre, on Friday, Sept. 15, Wu-Tang Clan frontman RZA hovered over his computer, smiling and quietly conversing with the DJ beside him. The two were positioned almost offstage that afternoon, preparing to provide a live-scoring of the 1978 kung fu movie The 36th Chamber of Shaolin. The crowd let out a roaring cheer as the hip-hop legend approached centre stage. He offered a few generic comments about the movie, apologized for the presence of a large timer on-screen—it was necessary for the “composers”—and returned to his shadowy booth.

RZA began with some breezy soul instrumentals over the opening credits. Mere minutes after this period of calm, a meticulously choreographed action scene exploded onto the screen, as RZA spun one of his abrasive bangers. The audience rapped along with the record in sheer elation.

The 36th Chamber of Shaolin is a fictionalized account of the life of San Te (Gordon Liu), a student living in 18th century China. After the brutal murders of his friends and family at the hands of the oppressive Manchu government, Te becomes determined to seek revenge—pleading for an opportunity to train at the famed temple of Shaolin. The exclusive sanctuary initially rejects the non-member, but the headmaster takes pity on him. He begins training persistently to join the temple as a master. RZA overlaid a montage of Te’s strenuous training with the downtempo “C.R.E.A.M,” setting the stage for an emotional climax.

A story of dedication, rebellion, and most importantly, mastering the three section staff (a prestigious Chinese flail weapon) the movie is rightly considered the apotheosis of martial arts pictures. Te’s master immediately notices his remarkable progress. He asks him to choose one of the 35 chambers to head—each is dedicated to mastering a specific aspect of kung fu. He requests instead to create a new chamber, one devoted to training the common man. Te is initially rejected, the elitist temple accepts only the rich and noble. However, after leading his country to victory, he is granted his wish. The film concludes with Te training laymen in the hitherto elitist art of kung fu.

The 36th Chamber of Shaolin is in command of its audience from the start. A palpable rush jolts the heart as the viewer watches the protagonist dodge the keen sword of his foe and quickly strike back. This adrenaline-like surge—which only the best action movies are able to bring about—heightened as RZA simultaneously played Wu-Tang’s “Bring Da Ruckus.”

At the end of the film, RZA returned to the stage and spoke about his personal connection to the film. As a child, he, his brother, and cousin (GZA and Ol’ Dirty Bastard, both Wu-Tang members) watched the movie on repeat. From this, they developed insatiable appetites for art.

Both the music and aesthetic of the Wu-Tang Clan are as fundamentally egalitarian as the concept of the 36th chamber. Their unpretentious songs are raw, simplistic, and to the point. Wu-Tang members don’t look or behave like platinum-selling superstars. They don hoodies and loose-fitting jeans, and rap about being on food stamps and mispronouncing words. The late Ol’ Dirty Bastard summed it up best at the Grammy’s in 1998 when—10 years before Kanye—he interrupted Puff Daddy’s Best Rap Album of the Year acceptance speech to declare that “Wu-Tang is for the children.”

RZA finished up his speech with some words about perseverance. He reminded the audience that only 25 years ago, he was unknown and destitute, trying to make his friends laugh by spitting absurd lyrics over stripped-down beats. When he closed the show, the audience shot to their feet and gave him a standing ovation. RZA and San Te are two souls separated only by two centuries.