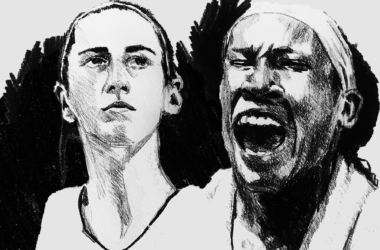

Although they agree that the lockout should end as soon as possible, two basketball fans give their take on who they support:

Owners

I’m an avid NBA fan, and like most other fans, I’m attracted to the league because of its players. We cheer for Kobe and Dwight because they’re the ones with the world-class talent. But after months of fruitless negotiation, I’m siding with the owners.

There are three main issues to evaluate. The first is the salary cap. Before the lockout, the NBA used a soft cap system, allowing teams to exceed the cap to re-sign their players. Because teams were allowed to exceed the cap threshold, they were given the opportunity to sign free agents to massive contracts. This created a system whereby a mediocre player like Rashard Lewis earns $21 million annually. The owners are pushing for a hard cap, which does not allow teams to exceed the cap threshold. This way, owners would be more cautious with their spending, and eventually, the average salary of players would decline. Players argue that it’s the owners’ faults for signing players to contracts that are totally disproportionate to their production. However, the motivation behind the owners’ hard cap system is to prevent this mistake. For instance, when a role player like Travis Outlaw is handed a five-year, $35 million contract, it increases the market price for other similar role players. This leads to a frenzy of ridiculous spending.

The second issue is revenue sharing. Under the previous Collective Bargaining Agreement, NBA teams were forced to share revenue only if they exceeded the luxury tax. On the surface, this gives a significant financial advantage to teams in larger markets, such as Los Angeles and New York. Teams in Indiana and Milwaukee struggle to build winning teams, and feel disadvantaged. The owners’ argument is that they shouldn’t have to share the money earned by their teams with others. In fact, there is no real correlation between greater revenue and on-court success. Teams in small markets without huge cashflows, such as San Antonio and Oklahoma City, have become some of the most successful franchises in the NBA. How did this come about? Simply, through the draft. In order to achieve success in the NBA, franchises must draft well. The New York Knicks are the wealthiest team in the NBA, and handed out money for years, but their last title came in 1973. Thus, it’s not certain that revenue sharing will lead to more success for small market teams.

The last issue, and probably the most polarizing one, pertains to Basketball Related Income, or what fans have come to know as BRI. In the 2010-2011 season, players earned 57 per cent of BRI, which includes ticket sales, television contracts, concessions, etc. The owners feel they are entitled to some more of that revenue, a completely fair claim since they are the ones funding the team. While the players are willing to share the revenue more evenly than the previous agreement, they rejected a dead-even 50-50 split. The average salary of the NBA player in the 2010-2011 season was $5.15 million, so it seems unreasonable to argue that they need more money. This is not to say that the owners need more money either, but the system is unfair. The BRI is based on gross revenue, so when the owners are spending extra funds on promoting and marketing their team, they’re taking a hit to their share. The players do not feel this hit, and should be willing to split the BRI evenly.

As an NBA fan, there is no winner in this dreaded situation, but a compromise must be reached, and as much as I love Dirk, I’m cheering for Mark Cuban.

– Steven Lampert

Players

This is like deciding between Glee and Dancing with the Stars on a Tuesday night … there’s no right way to go. The NBA and the NBPA are both to blame for the current NBA lockout. After last year’s season, one of the best ever, they had to find a way to get some kind of deal done in time for a season. But, if I have to take a side, I’m standing with the players, and so should you.

The owners claim they were losing money under the old CBA. We have to say “claim” because they haven’t been transparent with their books. Not the behaviour of men in white hats. Nevertheless, let’s assume that owners are losing money and do need to change the system drastically to make a profit, taking a greater share of Basketball Related Income (BRI) and instituting a hard cap system. So that means that owning a basketball team is not a great business investment? Thanks for stating the obvious. A sports franchise is not a business. It’s a toy for billionaires. If the owners want a guaranteed profit they should sell their teams and invest in gold. Or they should sort it out between themselves with revenue sharing. What they cannot do is expect the players to just hand over hundreds of millions of dollars without giving them something in return.

How would a hard cap system help the owners save money you ask? Under the old system, a soft cap allowed teams to go over the cap if they were willing to pay a luxury tax on every dollar spent over the cap. A hard cap would limit how much teams could spend, which would help owners save money and increase parity in the league, says the NBA. This is ridiculous. First of all, the owners already have a built-in device to limit overspending; it’s called common sense. Nets forward Travis Outlaw makes $7 million a year. If the Nets aren’t competitive and aren’t profitable, they deserve it. As for competitive balance, how about this: do your job. If you want to win, hire good coaches and GMs, draft well, re-sign players before they hit the open market, and build a culture of winning in your city. Consider the Knicks. They have plenty of money. They also hired a coach who literally doesn’t coach defence, at all. I’m going to go out on a limb and say they won’t win a title anytime soon, and they’ll have no one to blame but themselves.

These two issues, the cap system and the BRI split, seem to be the central points of contention in these negotiations. In both cases, the owners’ proposals aren’t outrageous, but they do require concessions from the players. On the other hand, the players are receiving nothing in return for these concessions. The owners expect the players to do these things for the good of the business as a whole, as if they were equal partners in the NBA. At the same time, the players aren’t being shown the respect a business partner deserves. The NBA has shown, with its series of ultimatums, ambushes, and condescending memos, that the owners see themselves at the top of the pyramid looking down on the players, which they are. They want the players to act like partners without treating them like partners, backing the players into a place where they feel like they need to stand up to bullies.

It’s hard to feel sympathy for millionaires, but don’t buy into the image of the players as greedy. If anything, their actions prove the opposite. They’re willing to lose a year of salary—money most of them will not recover whatever the new deal looks like—to stand up to the man

. Are you really going to side with the man?

– Haruki Nakagawa

Winner: Players

As entertaining as the owners can be (we’re looking at you, Mark Cuban), it’s the players that make the NBA what it is. They should benefit most from the league’s financial profits, and should be compensated accordingly.

Glossary

Basketball Related Income (BRI)—Accounts for most of the revenue generated by an NBA team. Includes, but is not limited to, ticket sales, television contracts, and concession sales.

Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA)—A legally-binding contract between management and employees that defines conditions of employment for a specified time period.

Hard cap—A salary limit that may not be exceeded for any reason. The current system is a soft cap, allowing teams to surpass the limit in exchange for revenue sharing.

Travis Outlaw—Formerly a talented NBA player. Now a case study against the owners.