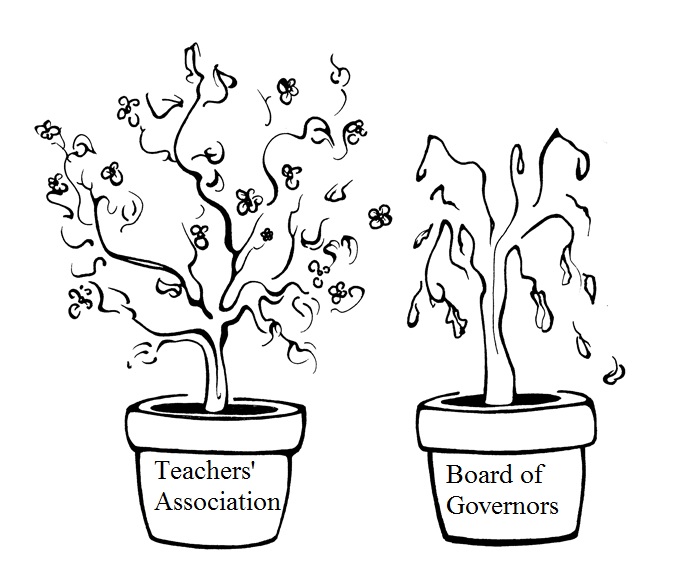

On Nov. 8, the McGill Association of University Teachers’ (MAUT) Council voted unanimously to divest from fossil fuels, moving approximately $500,000 out of its investment portfolios which include holdings in fossil fuel companies. The MAUT also passed a motion by a vote of 13-3 calling on McGill’s Board of Governors (BoG) to follow suit with the university’s endowment and pension fund.

The MAUT Council, which represents the university’s academic staff members in the McGill Senate and other national academic committees, asserted that the continued extraction of oil reserves by major fossil fuel companies hampers global efforts to mitigate climate change. Additionally, the council invoked McGill’s divestment from the South African apartheid regime in 1985 and from tobacco companies in 2007, and argued that McGill organizations have a duty to apply pressure on industries responsible for social injury.

“We each have a role to play to do what we can to support the environment,” MAUT President Alenoush Saroyan said. “We need to be on the right side of history on this one within our boundary of possibility.”

Supporters of the MAUT’s motions—which follow the Faculty of Arts’ endorsement of divestment in December 2015—hope that it will push the BoG to divest McGill’s pension plan and endowment of $1.5 billion; in 2012, Divest McGill, a student group on campus that lobbies for fossil fuel divestment, estimated that 5.7 per cent of this endowment was in fossil fuel, with The Montreal Gazette putting that number at about 5 per cent in 2015. Although he expects McGill’s divestment would have a minimal financial impact on the fossil fuel industry, Environmental Philosophy Professor and member of McGill Faculty for Divestment Gregory Mikkelson emphasized the political and moral dimensions of such an action and its potential to encourage discussion about environmental legislation.

“MAUT’s divestment of its own funds is a good demonstration that we are walking the walk as well as talking the talk,” Mikkelson said. “And if the alma mater of the Canadian prime minister took this step, it would have a huge symbolic political impact.”

Despite the recent victory, proponents of fossil fuel divestment face an uphill battle against the administration. In March 2016, the BoG accepted the Committee to Advise on Matters of Social Responsibility’s (CAMSR) recommendation not to divest McGill’s endowment. Members of the Committee argued that McGill could combat climate change more effectively through sustainability projects on campus such as the Vision 2020 program, a plan to reduce the university’s greenhouse gas emissions by nearly 13,500 tons over the next two years, and the Climate and Sustainability Action Plan to become carbon neutral by 2040.

“The Board, acting on the advice of […] CAMSR, has determined that the best way for McGill to address the very real problem of climate change is to take action that will make a difference,” BoG President Ram Panda wrote in a statement to the Tribune. “MAUT and other groups have different views on this subject [and] it is clear the conversation will continue and we look forward to it.”

Students activists will also remain engaged in this conversation, according to Jed Lenetsky, a Divest McGill organizer. According to Lenetsky, the group plans to continue soliciting community support for divestment in order to pressure the BoG into changing its stance. Lenetsky and other members of Divest McGill see the MAUT’s decision as a sign that the academic community disagrees with the BoG’s conclusion to not divest.

“It’s further evidence of how out there their decision making was when the association of McGill’s professors is openly disagreeing with the decisions made by the administration,” Lenetsky said.

Supporters of divestment remain optimistic at the movement’s prospects over the coming years.

“I think the BoG will divest eventually,” Mikkelson said. “It’s just a question of how much kicking and screaming is necessary.”