Flightless Birds

Flightless birds are an evolutionary puzzle. The most befuddling aspect of these seemingly-related animals is their dispersion across far corners of the earth, because, well, they’re flightless.

Two opposing ideas seek to explain the far-reaching origins of these birds. In one, Charles Darwin suggested that a common ancestor flew to new locations, where it then lost the ability to fly. The second theory proposes that flightless birds split away from each other on diverging continents. The discovery of three separate flightless ancestors, dating before Gondwana—a super continent that comprised most of the current the Southern Hemisphere—supports the second theory.

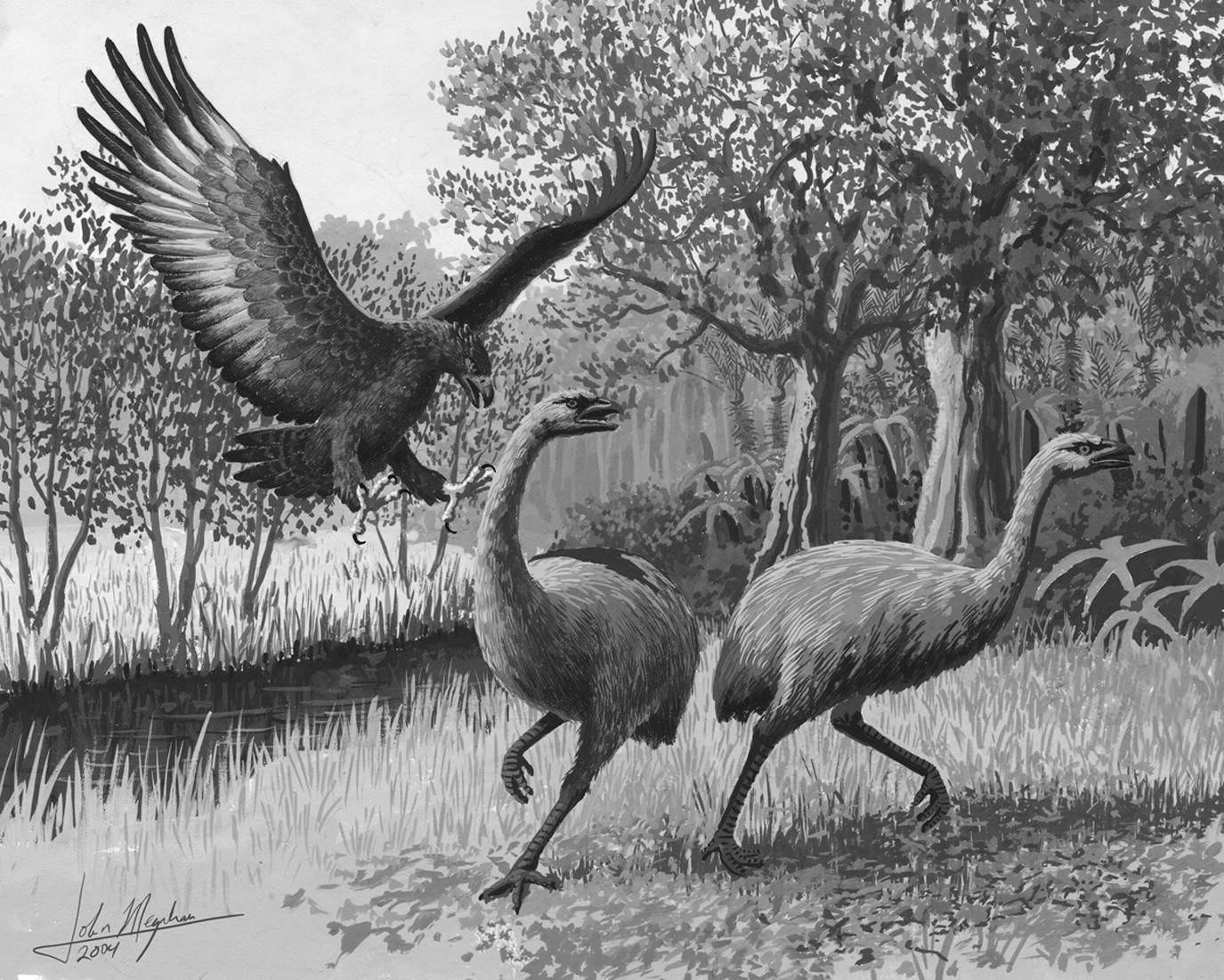

However, several years after this discovery, DNA evidence demonstrated that Moa—extinct flightless birds from New Zealand, which stood up to 3.6 metres high—were closely related to a flying bird in South America, suggesting that they had a flying ancestor.

Last week, Royal Ontario Museum researchers released new information showing that both theories may be right. By analyzing Moa DNA, researchers discovered that the bird started to evolve along several different paths after Gondwana split apart, but at least two ancestral lines were founded later by birds that flew to new locations. This new discovery highlights the nuance of evolutionary biology.

Volcanic Eruptions

Volcanic eruptions start small: gas bubbles form in magma, heat and expand, then finally shatter the surrounding rock with explosive force. Whether these explosions are small and mild, or large and catastrophic, depends largely on the first ten seconds of bubble formation.

This month, McGill Earth and Planetary Science Professor Ron R. Baker, in collaboration with an international team of scientists, examined this phenomenon in the lab, modelling the volcanic bubble formation process in basaltic rocks. After using a laser to super-heat the rock, the team was able to observe the bubbles growing with a specialized X-ray microscope—essentially, an ultra-precise CT scanner. By using the images to measure bubble size and wall thickness between bubbles, they were able to determine the explosive potential of different formations.

Extremely explosive basaltic volcanoes are rare—Hawaiian basaltic volcanoes are considered mild, despite the fact that they can shoot lava up to nine kilometres into the air—but understanding more about bubble formation will allow scientists to start chipping away at the problem of determining what conditions cause these catastrophic events to occur. This should lead to more accurate predictions of volcanic eruptions. Their findings are outlined in a recent paper in Nature Communications.

Global Food Security

Is it possible for the earth to produce enough food to feed its massive, multiplying population, or should we begin our move to Mars? A joint study by researchers at McGill and the University of Minnesota published in the interdisciplinary magazine Nature last month provides hope that humans can stick around if we manage our resources wisely.

Using a broad analysis of global farm production, the researchers compared overall crop yields from both high and low-performing farms in certain regions. Their analysis suggests that using existing farms to their full capacity could bolster global food production by anywhere from 45 to 70 per cent for most crops. This means increased agricultural output doesn’t have to come at the expense of pristine forests and ecosystems.

In addition, the study revealed that increasing productivity will not require an increased use of fertilizer, which is associated with pollution and drinking water contamination. Nitrogen and phosphorous usage, two of the biggest culprits in agricultural pollution, could in fact be reduced by 28 and 38 per cent respectively worldwide, without negatively impacting yields for major crops such as wheat, corn, and rice.

While the study seeks to present a general picture, rather than delving into the details of implementing such sweeping changes, the dramatic findings allow for optimism on this serious and timely (seven billion people and counting) problem.