While most McGill students are likely more interested in finding free food than understanding the biological processes that allow them to digest it, researchers at McGill are using new technologies to examine digestion, and other important physiological processes.

To determine exactly how the body digests without using human test subjects, Professor Satya Prakash of the biomedical engineering department has developed a machine which models the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This rare, specialized equipment gives the Prakash lab an edge. “In North America, it’s the only one,” Prakash said. “I’m very proud of that!”

The human GI model is made up of five vessels connected by tubes. Each vessel models the conditions in a different stage of human digestion: the stomach, the small intestine, and the ascending, transverse, and descending parts of the colon. Prakash uses computer controls to vary temperature, pH, and anaerobic conditions in the machine, adjusting these factors to reflect the real conditions found in the body.

Recently, the lab used the GI model to research probiotic bacteria, and how they are affected by the amount of time they spend in the GI tract.

While research using the in vitro human GI model is invaluable for studies such as the probiotics project, it is only one of the many interesting areas of research Prakash’s lab pursues. Another project gaining momentum is a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s which involves developing a platform to deliver drugs to the brain.

“We designed … a nanoparticle that has a special tag on it that can deliver through the blood brain barrier,” Prakash said. “It leads to a specific part of the brain so it can deliver a drug.”

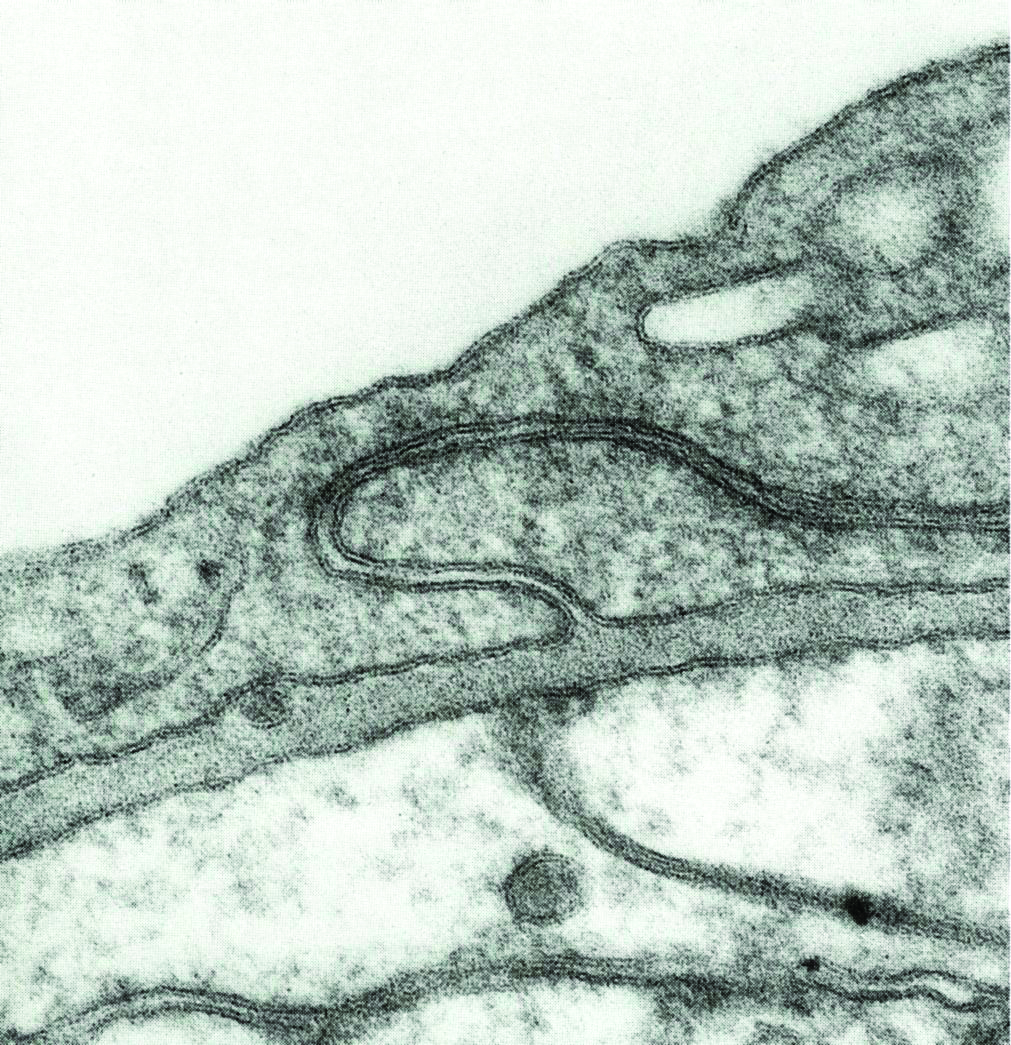

Traditionally, it has been very difficult to get drugs circulating in the blood across the blood-brain barrier. This is because the brain is equipped with extra defence mechanisms to keep out unidentified molecules. One way of overcoming this challenge is to use a targeted nanoparticle; these particles are small enough that, with the help of the targeting molecules on their surfaces, they can slip through the defences and reach the desired part of the brain. While Prakash’s current project is a nanoparticle designed to treat Alzheimer’s, by changing the target molecule, it could ultimately be directed to many different sites in the brain and used to treat a variety of diseases.

Given the breadth of research projects conducted in the lab—from probiotics to Alzheimer’s treatments—the team is drawn from a multitude of different backgrounds with a variety of experience. Although some supervisors would find it daunting to coordinate the diverse lab members, Prakash seems to revel in the interdisciplinary nature of his lab.

“In my group there are a physician, microbiologist, a biochemist, a chemist, a … chemical engineer, a food scientist, … a mechanical engineer, [and] biolog[ist] … These are the group member[s] that I have now. A different assortment, it’s fun!”