F or most people in Montreal, a walk through the city’s downtown area is part of the daily commute to school or work. Immersed in their routine, most commuters will not notice—or will pretend not to notice—the long-faced strangers sitting along the sidewalks, holding their cups in hope of a few cents from a passer by.

or most people in Montreal, a walk through the city’s downtown area is part of the daily commute to school or work. Immersed in their routine, most commuters will not notice—or will pretend not to notice—the long-faced strangers sitting along the sidewalks, holding their cups in hope of a few cents from a passer by.

It is so commonplace to see homeless men and women sitting on the pavement asking for money, or sleeping in small corners and down alleyways, that they fade into the background. The constant threat of violence and exposure to the elements is inherent to their way of life. The Montreal winter is harsh, and these are the people who will feel it the most. And in the summer, the risk of dehydration can be just as fatal as the winter’s biting cold. Many congregate in places like Berri Square, where drugs and alcohol make for a dangerous environment, or take refuge underneath bridges, in desolate parks, or in the ruins of an abandoned building, living in the most degrading and unsanitary of conditions.

The transitory nature of homelessness makes it difficult to put a number on how many people are without homes in a city. However, according to Matthew Pearce, the general director of the Old Brewery Mission (OBM)—the largest organization for homeless men and women in Quebec—there are “between four and five thousand people on the street in Montreal at the moment. OBM provides services to around four thousand per year.”

“All kinds of people stay here at the shelter, not just the stereotype. Doctors, mechanics, lawyers, blue collar workers, white collar workers. Everyone has a story to tell,” said Dave, resident of the Old Brewery Mission. For five years, he has been staying on and off at the Webster Pavilion, a shelter of the OBM located just off St. Laurent by old Montreal, where he has a place to sleep and an evening meal.

Homelessness in the city of Montreal develops and spreads alongside wealth and prosperity. Every year, thousands of students and young professionals migrate into the city, attracted by its economic dynamism, its reputation as a center of higher learning, and the promised advantages of living in a welfare system that ensures the wellbeing of its citizens.

Yet, while Montreal’s towering skyscrapers and constant activity serve as reminders of its wealth, it is unavoidable not to ask: how is it that so many people are still hungry and living on the streets in such an affluent city?

Yet, while Montreal’s towering skyscrapers and constant activity serve as reminders of its wealth, it is unavoidable not to ask: how is it that so many people are still hungry and living on the streets in such an affluent city?

The common perception that homelessness is caused by personal failings belies the complex relationship that exists between personal circumstances, such as disability and mental illness, and societal factors that are entirely out of the individuals’ control.

Each year, poorly treated mental health issues draw hundreds of people to the streets, Pearce explains. “People with mental health issues form about 50 percent of the entire homeless population.”

Although it seems counterintuitive that those with mental illnesses are left to fend for themselves, this abandonment is the norm rather than the exception. It is the direct result of a policy of deinstitutionalization that has been prevalent in North American healthcare since the 70s.

The advent of drugs that manage psychotic episodes among those who suffer from mental health disorders, or developmental disabilities has replaced, to some extent, long stay psychiatric hospitals with less restrictive mental health services. The policy was meant to emancipate the mentally ill from straitjackets and stigma, but in some cases it seems to have simply relocated them to begging for food in the streets, or getting incarcerated for their conduct.

Sylvain, another OBM regular, can account for the harm done with this transition.

Sylvain, another OBM regular, can account for the harm done with this transition.

“I suffer from mental illness and that is the reason for my staying at the Old Brewery Mission. I endured years of torment after being misdiagnosed and using medication that worsened my situation,” he said.

Though prevalent, mental health is not the only reason why thousands of people find themselves living on the streets of Montreal today. When asked what the biggest barrier to sustainably reducing homelessness in the city is, Pearce answered: “insufficient affordable housing.”

According to the international public policy firm Demographia, housing affordability in Montreal has steadily deteriorated in recent years. This increase in costs is a reality to which OBM resident Dave can attest.

“My mom lives in Montreal. She developed Alzheimer’s disease a few years ago, so much of my time is spent here. I can’t afford any kind of accommodation [in the city], so I have to stay at the Old Brewery Mission,” he said.

Dave’s situation is just one example of how a lack of affordable housing makes many Montrealers resort to staying at one of the few shelters in the city. With this in mind, the Mission is making changes to its service. Aside from being a shelter, it also offers transition programs to help the homeless integrate back into society, which includes providing affordable housing for homeless individuals. In the last five years, the organization has increased the number of housing units available to homeless people from 30 to 74; but there is still much to be done.

Insufficient housing in the city has affected Montreal’s Indigenous population disproportionately.

The last 12 years have seen a rise in Inuit migration to Montreal, and this has gone hand in hand with their increasing over-representation among Montreal’s homeless. The Inuit account for 10 percent of the Indigenous population in the city, and around half of the Indigenous homeless.

Donat Savoie, the legal representative of Quebec’s Inuit people, sees the rise in Inuit homeless in Montreal to be closely related to the acute housing crisis which has been occurring in Inuit communities in Quebec over the past few years. This housing crisis goes some way to explain why there are so many homeless Inuit in Montreal.

Savoie describes Nunavik, a large region in Northern Quebec, from where around two thirds of homeless Inuit in Montreal originate, as “toxic.” It is not uncommon to find 12 to 15 people per house in the 14 coastal communities there. According to Savoie’s latest report, the housing crisis is so severe that 1,000 homes are needed urgently. However, the difficulty of transporting materials makes for high building costs, and the federal government has yet to implement a catch-up program to help the Nunavik communities.

Savoie describes Nunavik, a large region in Northern Quebec, from where around two thirds of homeless Inuit in Montreal originate, as “toxic.” It is not uncommon to find 12 to 15 people per house in the 14 coastal communities there. According to Savoie’s latest report, the housing crisis is so severe that 1,000 homes are needed urgently. However, the difficulty of transporting materials makes for high building costs, and the federal government has yet to implement a catch-up program to help the Nunavik communities.

This overcrowding is a breeding ground for physical and sexual abuse against women and children, and one reason why Inuit are attracted to Montreal is to escape poverty and abuse at home. The current situation is becoming all too familiar—the Inuit, stifled by conditions in Northern Quebec, come to Montreal in search of security, but find the city unwelcoming and end up without a job and on the street. Over half of all adult Inuit in Montreal are currently unemployed, and this situation is worsened by minimal community support and lack of knowledge of French.

What kind of future awaits for the homeless of Montreal? The fact is, there is little political payoff in committing resources to bring people out of homelessness. The Old Brewery Mission has expressed in its latest annual report a need for more government funding, but few votes are won by helping such an ostracized group. It remains to be seen whether provincial authorities will adopt a more active stance towards helping the Inuit of Nunavik, and all those in Montreal who remain without a home.

Photos by Simon Poitrimolt and Sam Reynolds

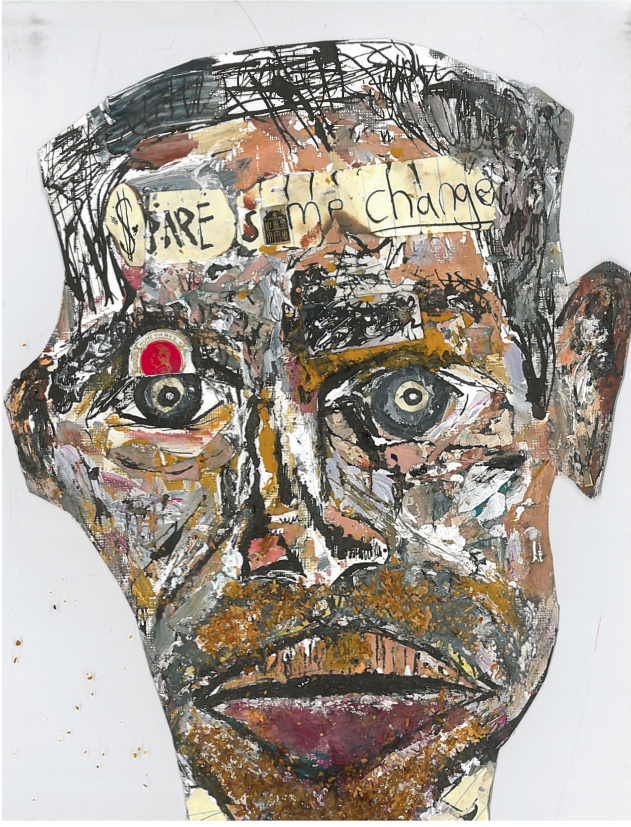

Lead artwork by Tyler Berry