Until recently, a postmortem analysis of brain tissue was the only method capable of confirming that a patient suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, as opposed to another mental illness. Despite the many real-time medical assessments available, such as blood tests, brain scans and neuropsychological tests, none of these results are definitive. With no means to acquire a conclusive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease before the illness has run its course, there is a dire need for a quick and non-invasive alternative.

In the past few years, the focus on blood-based approaches to diagnose patients with Alzheimer’s disease has increased exponentially. Researchers have generated a list of blood-based proteins more commonly found in those afflicted, compared to healthy individuals, patients with other forms of neurodegenerative disease, such as Parkinson’s, or those with mild cognitive impairments. Based on the existence of such biomarkers in the bloodstream and various personal characteristics, including age and education, a derived algorithm could correctly identify patients with Alzheimer’s disease with moderate accuracy.

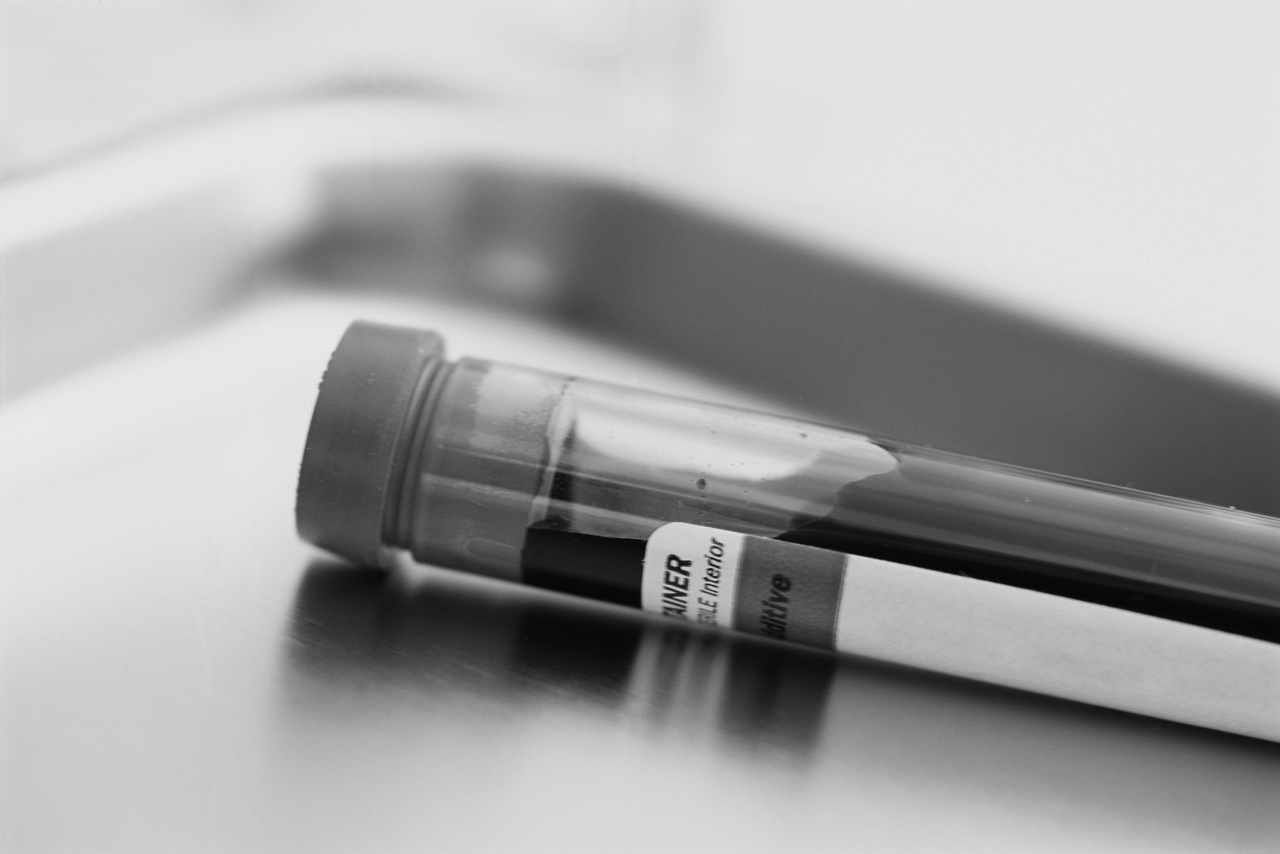

Recently, a team led by Dr. Vassilios Papadopoulos, director of the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, made a major breakthrough in blood-based diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. The researchers believe they have developed a blood test that can detect Alzheimer’s in its early stages, well before patients exhibit the disorder’s characteristic advanced signs, previously used for diagnosis.

The team built on their previous work on alternative pathways in DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone) formation—a brain hormone—to develop a method to distinguish between patients with Alzheimer’s disease and healthy individuals or those with mild cognitive impairment.

The test is based on subjecting a blood sample to a chemical reaction known as oxidation, the concept underlying rusting metals. When the blood of healthy individuals is oxidized, they generate high levels of DHEA as a method of protection against oxidative stress. In contrast, patients suffering from Alzheimer’s did not showed marked changes in DHEA levels.

The team successfully replicated their findings from animal models and in vitro brain tissue in a clinical sample—a major step towards the creation of a blood-based diagnostic tool for Alzheimer’s disease.

While progress has been made towards developing a blood-based diagnostic test, the end of the search is not quite near. Studies on blood-based biomarkers (proteins in the blood) have identified panels of up to 30 different biomarkers to probe for—and there is little overlap between the studies. This lack of consistency between studies indicates that the perfect set of blood-based identifiers of Alzheimer’s disease remains elusive. Also, replication of these findings in larger sample sizes is necessary prior to making these tests available in clinical settings.

Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease also raises a slew of ethical concerns. Alzheimer’s is an irreversible neurodegenerative disorder with no definitive preventive measure or cure—would it really help patients to confront this prognosis in their youth? However, there is emerging evidence that early interventions and diagnosis, especially prior to onset of symptoms, can improve quality of life in both patients and caregivers. As Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, predicted to affect one in 85 adults globally by 2050, the development of a rapid non-invasive diagnostic tool is critical in its management.