Living in the small Middle Eastern country of Kuwait for my entire life, teenagers often romanticized the easy-going university hook-up culture that we watched in Western movies and Netflix rom-coms. Much like many other first-year students, when I came to university I was thrilled to be away from a place where I knew everyone I went to school with, leaving serious dating and heartache behind. I was captivated by the thought of meaningless fun with strangers and throwing emotional baggage out the window.

My first semester did not disappoint. I nosedived into McGill’s pool of careless hookups, feeling both very excited, and very overwhelmed. Orientation and Frosh events encouraged only surface level bonding with the people around me, since I encountered hundreds of new strangers at each party. The anonymity of it all brought life to the same culture that existed in the movies: A steamy hookup without consequence.

Yet, the instant gratification of a match or a date wore off fast and hard, and my fragile ego needed to be constantly fed. It was unsustainable. I started to connect my self-worth to how many people were attracted to me. I began losing friends and dismissing people who truly cared about me because the ego-boost of a hook-up felt more satisfying than long-term friendship. It was destructive—both for my self-confidence and the relationships that should have mattered to me the most.

With Frosh comes enormous social pressure for first-years to hook-up with other froshies. As a result, orientation events can alienate those who aren’t comfortable with a one-night stand, and it sets the tone for one’s entire university experience. Beyond romantic connection, the shallow Frosh environment makes it difficult to foster worthwhile friendships through its impersonal gatherings. The McGill community hook-up culture in and of itself isn’t the problem, however. To be healthy and happy, students should be mindful of how that culture affects them personally. For me, that meant suppressing deep emotional issues and neglecting my own emotional awareness.

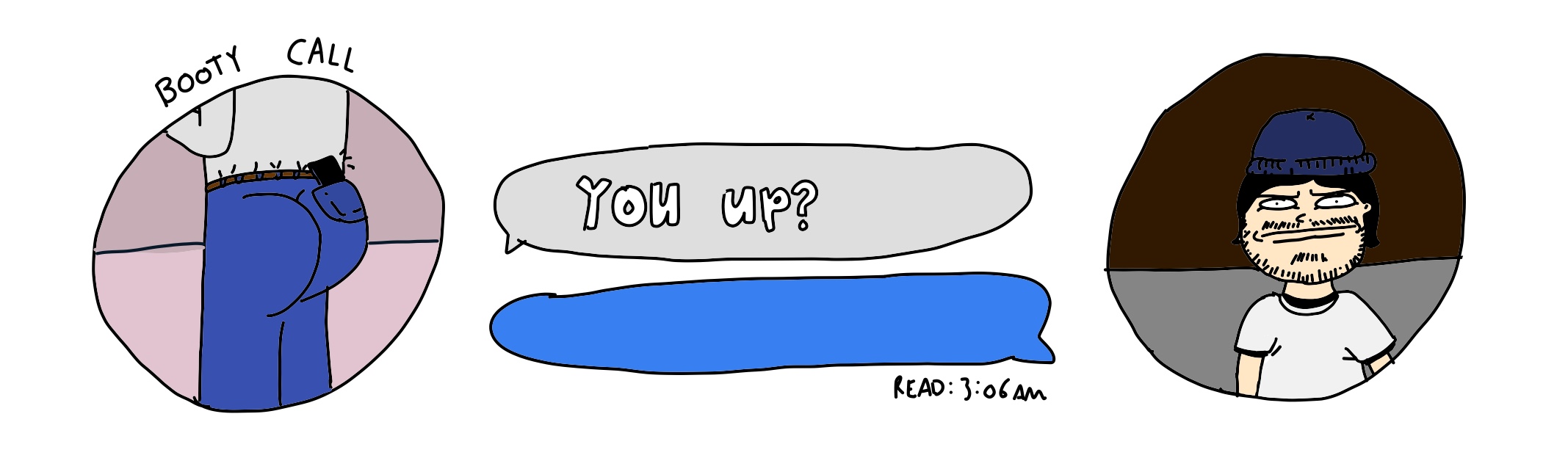

I have an on-going joke with my friend that she’s attracted to emotional unavailability because she doesn’t want to handle anyone else’s emotional baggage or to have deep romantic commitments. Like many of us on campus, she finds temporary relief from the instantly-gratifying Tinder match or one night stand. These types of transient romantic connections can provide an ego boost, but the confidence never seems to stick. For me, it started with a few Tinder swipes a day, to constantly swiping through class, to eventually making it a ritual before going to sleep. I grew less emotionally available in the process, clinging to hookups rather than real commitment. I thought I was protecting myself from the hurt that could come with the loss of a relationship by avoiding sensitive emotions.

Hookup culture is definitely not a bad thing. Exploration is important, especially for people such as myself who come from sheltered backgrounds. Furthermore, some people don’t always want to engage in a more serious relationship, or don’t have the time or energy to sustain one. Different relationships work for different people.

At the end of the day, no matter how great the hook-up is, too many people go back to their empty apartments and the gratification has already worn off. In my experience, acknowledging that hook-up culture wasn’t always for me made me realize that I might need to consider my emotions more, and ask myself why my actions felt so hollow. I threw myself into hookups thinking they were going to solve my confidence issues and my fear of rejection. I found myself yearning for a deep emotional connection, even if that meant accepting the risk of feeling the not-so-great emotions, too. It is easier said than done, but acknowledging my emotional unavailability when hook-ups weren’t working was a step in regaining my emotional connections with those around me, and better understanding what my psyche needed.