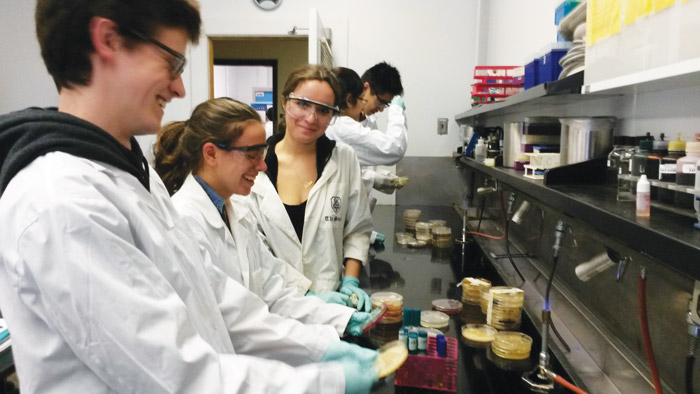

Unlike traditional courses, where students perform predictable experiments to learn laboratory techniques, MIMM 212’s (Laboratory in Microbiology) students are on the front lines of scientific research.

The course is part of the Small World Initiative (SWI), a project based out of Yale University that seeks to engage undergraduates in scientific research tackling the real-world problem of antibiotic resistance. Students in the lab are challenged to learn standard laboratory procedures and apply them to their own research projects. The SWI has partners in over 50 academic institutions, with McGill as the first Canadian university to join the initiative and as one of the first international partners.

MIMM 212 was revamped for Fall 2014 to align with the SWI’s objectives by having students analyze local soil samples and search for antibiotic-producing microorganisms. Student response has been overwhelmingly positive. Among the reasons for this support is the way that the course allows students to experience conducting research.

“I appreciated that our labs built on previous weeks,” Jessica Yudcovitch, U1 Science, explained. “I think it made it a more realistic experience in regards to actual laboratory research.”

According to Daniel Huang, U1 Science, the potential ramifications of the results of the lab’s experiments in the real world were also a highlight of the course.

“The course focuses on a real issue [antibiotic resistance] that’s affecting thousands of people, so it provides more than just learning standard lab techniques like growing bacteria or doing PCRs,” Huang said. “Everything was geared towards finding new bacterial species that could produce novel antibiotics to tackle the rise of bacterial superbugs, which makes doing well on all the experiments and focusing on all the pre-lab lectures easier, more important, and much more meaningful.”

Despite the course’s success, the process of designing a course in which the results of experiments are not known ahead of time can be difficult.

“One challenge was reacting to the results [that] the students were getting in real time,” said course professor Samantha Gruenheid. “The major goal of the course is to identify and characterize antibiotic-producing bacterial strains from the soil. At the beginning of the term, I didn’t know how many of the students’ bacterial isolates would have this activity. What if there were very few? What would we do for the rest of the term?”

The shift in the course’s focus from rote memorization and mastering routine tasks to a more open-ended project means that the course is continuously evolving.

“At first, I think it was an adjustment for them to be given the freedom and some of them took some time to build up their confidence to make their own decisions about their projects,” Gruenheid said. “Maybe a few of them were thinking ‘Just tell me what I need to memorize to do well in this class.’ However, when I saw the presentations at the end of the year, I was really impressed. In addition to learning the lab skills, I think they learned a lot more about thinking, researching, and communicating like a scientist.”

Students currently enrolled in the course have praised its unconventional structure.

“I would absolutely recommend this course to other students,” said Liz Harvey, U1 Science. “The grading is fair, the people are great, and the work is meaningful.”