There’s no avoiding the fact that university students today are stressed. According to a 2013 study conducted by the Canadian Association of College and University Student Services (CACUSS), 85 per cent of students reported feeling overwhelmed by their work

Of the study’s 30,000 respondents, 91.5 per cent admitted to feeling tired or drained in the past week.

“I have eight hours a day when I sleep, and then the rest [of my time] is for school and work,” said Haejoo Oh, a U0 Management student. “Especially with midterms.”

Stress is the body’s reaction to threats. Under stress, the hormones cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline are released and cause a cascade of physiological effects—heart rate increases, the liver produces more glucose, and blood is directed towards the muscles in the arms and legs. This allows the body to deal with the perceived threat, generating the fight or flight response. Today, however, the stress encountered by students is generally looming term paper deadlines, final exams, and the myriad of pressures caused by student life. As a result, stress shifts from being an acute physiological adaptation to a chronic state.

Chronic stress can cause insomnia and depression, increase vulnerability to infection, and increase the risk of diabetes and heart disease. This is especially concerning given that over 57 per cent of students in the CACUSS study reported experiencing above average to tremendous levels of stress.

The effects of stress will also undoubtedly impact students’ academic lives. In the CACUSS study, more students’ academic performances were negatively affected by stress than by physical illness, relationship problems, or learning disabilities.

Reducing stress levels can provide several benefits, such as improving attentiveness, sleep quality, and immune function.

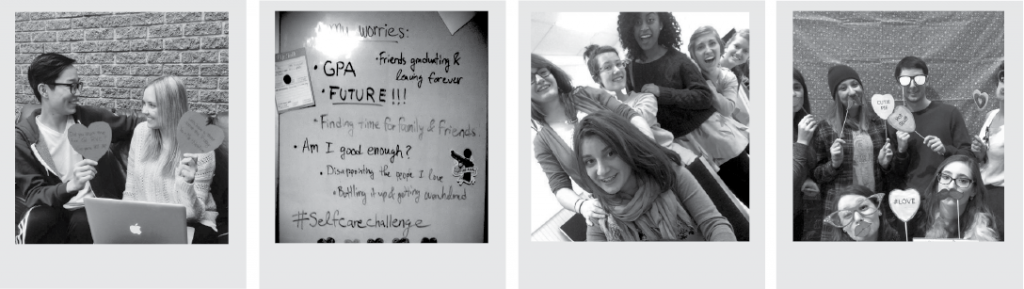

To promote stress reduction, Healthy McGill’s Self Care Challenge is starting conversations about mental health and stress. The challenge encourages students to look after themselves by engaging in activities like exercising, eating healthily, and drinking plenty of water.

“Self care can be anything from making sure that you know your limits with partying and drinking, to getting help when you need it, to just on a day-to-day basis trying to live a healthier lifestyle,” said Healthy McGill coordinator Amanda Unruh.

This concept of taking time to look after themselves can be hard for undergrads, but is immensely valuable.

“I think that, especially as students, we often feel like we don’t have time to take care of ourselves,” said Alice Gauntley, a U2 student and sexual health peer educator with Healthy McGill. “[Engaging in self-care] is a really great thing to do, especially this time of year when school can get really intense.”

The challenge is a way to inspire students to think more about mental health and dealing with stress, and also to create an environment where self-care and stress are talked about more openly, explains Unruh.

“We put together this challenge [because] we really wanted to create a campus culture of self care, where that’s affirmed and encouraged,” Unruh explained. “It’s been really great to be watching it on social media, especially to watch people doing a challenge with friends. It creates a culture of support.”

Whether initiatives like the self care challenge succeed in creating this culture of support is yet to be determined. In the meantime, stressed-out students have a range of support systems available, including the McGill Peer Support Network and free counselling services.