Human interactions are made up of complex exchanges of movements, sounds, and smells. In fact, researchers from the Sequence Production Lab at McGill University have shown that people are able to detect emotions simply by watching how people move their head.

The work was conducted by Professor Caroline Palmer from the Department of Psychology and Steven Livingstone, a post-doctorate fellow at McMaster University.

To prove their theory, the team recruited 12 adults to speak and sing a sentence with varying degrees of emotions, including happiness, sadness, and neutrality.

“We found […] that [the participants] used the same kind of head movements when they were singing a happy tune, [or] when they were speaking a happy sentence,” Palmer explained. “This suggests that there is something about the head movements that goes beyond the lexical content.”

In the second part of the study, the team had subjects watch videos of the participants that had been recorded—with their faces blurred and the sound muted. But the ability to interpret these physical ‘micro’ movements by an individual was still observed.

“Viewers could identify the emotional state from videos of the head movements during speaking or singing,” explained Palmer. “This means that those head movements really are conveying something that is not just specific to the words.”

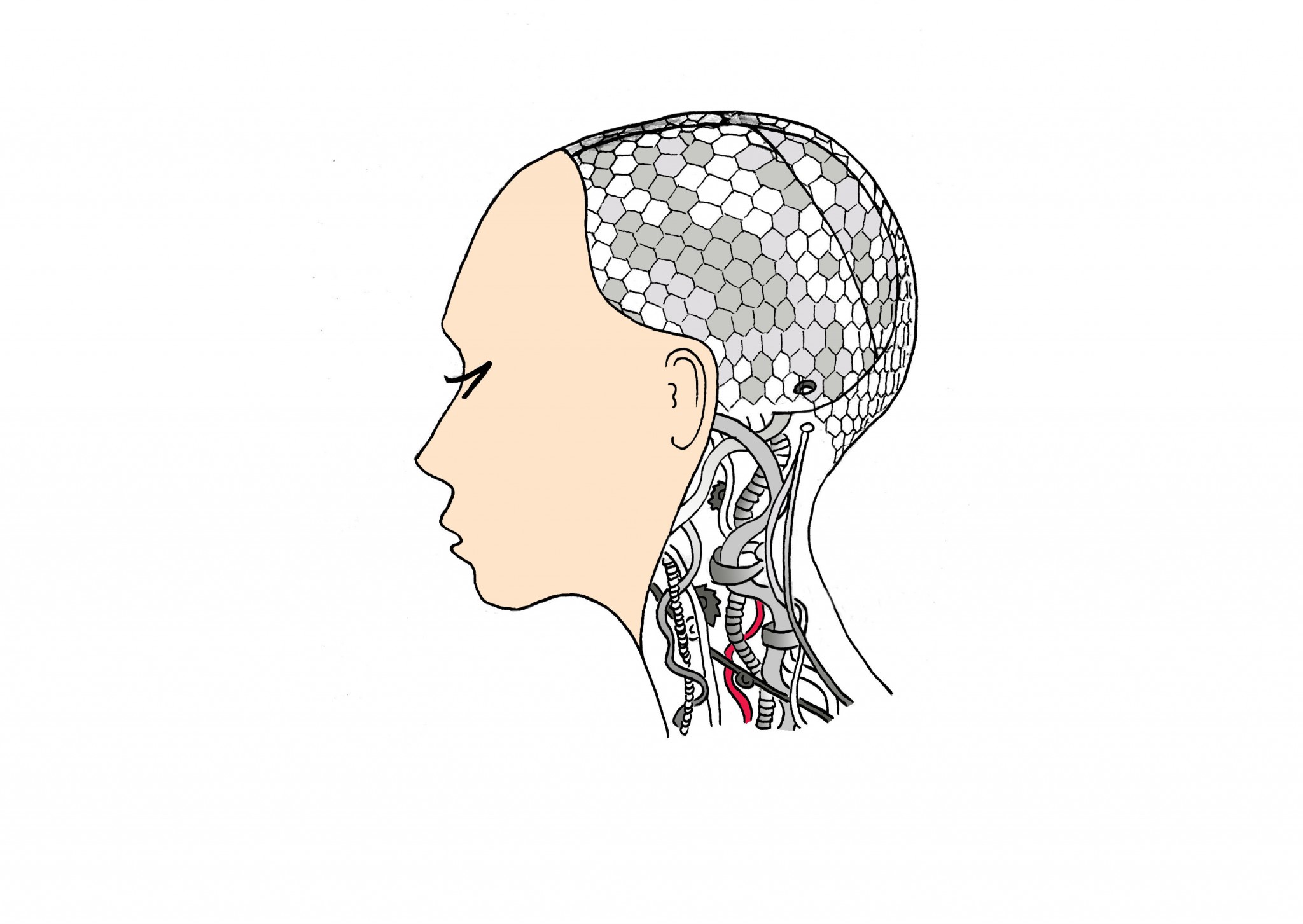

Aside from offering greater insight into the human mind, research in this field is useful for those involved in the development of artificially intelligent (AI) systems.

“[This discovery] can give us the chance to encode these cues in an intelligent machine, because those head movements seem to transcend speech,” Palmer stated.

“[These systems should be] capable of adapting their behavior by sensing and interpreting their environment, making decisions and plans, and then carrying out those plans using physical actions,” the statement read.

A hallmark of AI research is the hope of passing the Turing Test—developed by Alan Turing—where a human attempts to discern whether they are speaking to another human or a robot based on verbal cues. If the robot is thought to be human for the majority of the conversation, then the robot is said to have passed the Turing Test. In the evaluation of both verbal and non-verbal cues, however, human-robot interactions can result in the observation of new phenomena.

“There’s a term in computer science called [the] ‘uncanny valley,’” Livingstone said. “[When] something is close to being real, but is not real, [it can] make you feel a little uncomfortable.”

By studying and understanding head movements, androids could be given the ability to detect expression of information and emotion. This would enable them to understand people’s emotions and interact with a human more accurately, thus avoiding the uncanny valley.

While the thought of a robot acting exactly like a human may seem like something from a science fiction movie, these emotionally intelligent robots could eventually find themselves a place in society. For example, these kinds of systems could also aid in the long-distance care of patients.

“There are some lines of work developing robots to deliver standardized care to people either in hospital settings or stay-at-home individuals who don’t have the ability to get out,” Palmer stated. “This […] may include a nurse checking in on how a patient is doing at home, [after receiving information from a robot about their emotional state].”

Palmer hopes to further investigate this phenomenon with musicians, who often use non-verbal forms of communication when performing together.

“It seems very reasonable that some people will respond better to [a] machine that conveys emotion the way [a] human [does,]” Palmer said. “[Today,] machines are not known for conveying emotions because it is a very difficult state to model.”

As technology evolves, the materials needed to build robots improves. Consequently, the difficulty of building a robot continues to decrease. If researchers are able to emulate human emotions as well, then the future of AI robots is bright.