In response to high rates of HIV and AIDS within the province, a group of Saskatchewan physicians is urging the provincial government to declare a public health emergency.

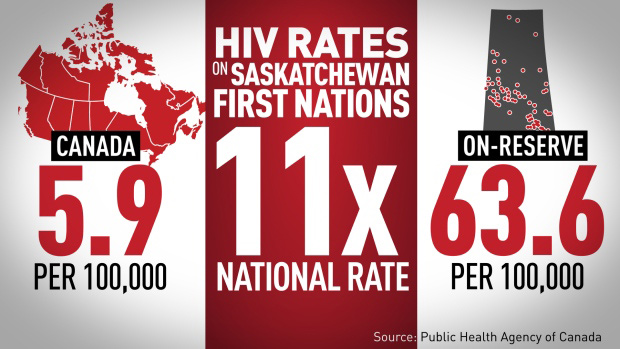

According to an open letter signed by a group of 30 physicians on Sept. 19, the 2015 provincial rate of HIV was 13.8 cases per 100,000 people; this is more than double the national rate of 5.8. For decades, the province has reported the highest rates of the infectious disease in Canada. Rates are especially high in indigenous communities, which account for 70 per cent of all cases in Saskatchewan despite comprising only 20 per cent of the population.

“We perceive this to be an emergency,” said Dr. Stephen Sanche, one of the physicians who discussed Saskatchewan’s HIV crisis at a press conference on Sept. 19th. "It calls for immediate action, and that’s really what we're asking for here.”

Between 2010 and 2014, the Saskatchewan provincial government implemented a strategy targeting HIV/AIDS, which successfully saw rates of HIV testing increase. However, since its expiry, there has been a sharp increase in the number of new HIV cases in the province, with 158 cases in 2015 compared to just 114 in 2014.

“[HIV] is a problem of discrimination, marginalization, […] punitive legal laws [and] notification services,” said Dr. Nitika Pant Pai, an associate professor in McGill's Department of Medicine and leader of the team that created the HIVSmart! mobile-based self-testing app. "[We must fight against] a culture where people are scared to get tested.”

To change the trend of HIV in Saskatchewan, it is also important to address the factors directly influencing the social stigma of the disease.

“Part of reducing stigma is to normalize testing, being diagnosed and being treated,” said Dr. Joseph Cox, an associate professor in the Department of Epidemiology at McGill. “Informed leadership is needed in educating the general population, and risk groups, about HIV and what it means today. The Saskatchewan example […] highlights how quickly infectious diseases like HIV can spread among networks of people when prevention programs are not sufficiently developed or deployed.”

In their letter, the doctors call on the government to adopt and achieve the UNAIDS recommended 90-90-90 goal by 2020. The UNAIDS goal urges governments to make changes to see that 90 per cent of those with HIV get tested and are aware of their diagnosis, 90 per cent of those diagnosed are put on antiretroviral treatments, and 90 per cent of those on treatment reduce the number of viruses in their bodies to prevent further transmission.

“[90-90-90] is a goal for every country in the world,” explained Dr. Catherine Hankins, a former McGill professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics who recently retired as the chief scientific officer for UNAIDS. “[There are] countries in Africa that are close to reaching those targets, while Canada as a whole is not.”

Saskatchewan has pushed back. According to the Canadian Medical Association Journal, the province has not endorsed the 90-90-90 goal. Dr. Denise Werker, Saskatchewan’s Deputy Chief Provincial Medical Health Officer, has thus far declined to declare a state of public health emergency as she says it’s impossible to do so when the term, “state of public health emergency,” doesn’t technically exist under the provincial health act.

According to Hankins, the HIV/AIDS crisis in Saskatchewan is propagating rapidly, and will continue to do so regardless of political agendas.

“What they [need to] do immediately, is make anti-retroviral [treatment] free of charge and offer it […] as soon as HIV is diagnosed,” said Hankins.

In the open letter, the physicians calculate that each new HIV case costs the provincial government nearly $500,000 on medication alone, in comparison with the $1.4 million it costs the province to support an HIV-positive patient throughout their lifetime. To lessen the financial burden, it is in Saskatchewan’s best interest to decrease the number of new HIV cases.

In addition to high costs, access to medication can also be a roadblock for some patients, particularly in indigenous communities. HIV has historically been associated with homosexual men, but increasingly the epidemic has moved to indigenous populations. As indigenous populations make up the majority of new HIV cases in Saskatchewan, it is critical to focus efforts on the populations most affected by the modern HIV crisis.