In 1964, Walter Byers, the first National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) commissioner, created the term “student-athlete” in order to counter attempts to make American universities compensate athletes for their contributions. Ever since, the NCAA has advertised itself as a generous non-profit organization that rewards its athletes with opportunities to get an education and to audition for a career in professional sports.

It is impossible to be fond of this twisted charity. The NCAA is an example of unfettered capitalism that is only sustainable if athletes remain under the guise of amateurism–preventing them from being compensated at fair market value. Within this system, Division I football and basketball teams are the cash cows of the NCAA. As a matter of fact, the University of Alabama football team’s revenues last year totaled $143 million, exceeding those of all 30 NHL teams and 25 of the 30 NBA teams.

In college basketball, the NCAA just agreed to a eight-year, $8.8 billion extension to its TV deal with CBS giving the network the rights to broadcast March Madness through 2032. Now, producing nearly $1 billion in annual revenue, there is a huge dissonance between revenue stream and player compensation. A study from Drexel University reveals, “the average full athletic scholarship is worth approximately $23,204/year, the study also estimates that the average annual fair market value of big time college football and men’s basketball players to be $137,357 and $289,031 respectively.” With this in mind, it is safe to say that football and basketball players are not compensated equitably.

American student-athletes are not playing intramural sports. Rather, these young men and women practice at levels similar to professional athletes. Statistics indicate that NCAA athletes spend more than 43.3 hours per week in practice, weight rooms, and games. Add this to a full school workload, and it is not surprising to see “students” develop mental health issues .

Thanks to their gruelling schedules, many of these student-athletes are unable to complete the student half of their designation. Approximately 40 per cent of student athletes on scholarships do not graduate within six years at university.

While university scholarships cover tuition, they often do not cover other indispensable costs, such as for food. More often than not, the well-being of student-athletes is sacrificed for the sake of amateurism.

“Sometimes, there's hungry nights where I'm not able to eat, but I still have to play up to my capabilities,” former University of Connecticut basketball player Shabazz Napier said when asked about his athletic college experience.

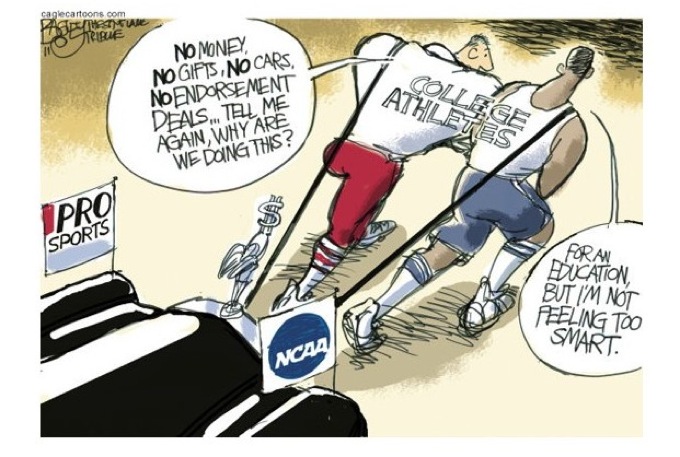

In spite of players’ immense contributions, it is their coaches who are awarded the most, with millions of dollars in contracts from various sources. The NCAA Manual explicitly allows coaches to sign endorsement contracts with athletics shoes, apparel, or equipment manufacturers, but prevents players from signing such deals. In fact, NCAA athletes are prohibited to use their image and status as public figures to gain any kind of income. These regulations prohibit players from receiving monetary benefits from the university brands they promote.

The NCAA system is an example of exploitative gain at the expense of unpaid labour. Despite the hypocrisy, the NCAA is unlikely to abandon its present practice and recognize its athletes as integral partners to the success of college sports. Letting athletes benefit from their fame and status by allowing them to receive endorsement money outside of the NCAA jurisdiction could in fact bring balance to this unreasonable system, especially for the undrafted athletes who invested four years of blood, sweat, and tears to the profit of the NCAA monster.