Fall 2018 marked the 25th anniversary of Lynn Hill’s historic first all-free ascent of the ‘Nose,’ an iconic climb in the Yosemite Valley. Since then, much has changed in the climbing world, but her massive achievement still stands tall.

The Nose is the route that snakes up between the two main faces of the monolithic El Capitan. The total elevation gain is 880 metres—twice the height of the Empire State Building.

Yosemite was a hotbed for American climbing culture in the mid-20th century, so athletes had already climbed El Capitan, one of the valley’s crown jewels, before Hill arrived on the scene. On the first ascent of the Nose in 1958, Warren Harding used climbing aids, allowing him to fix anchors to the rock and pull himself upward. In contrast, Hill climbed free: Although she used rope for protection, Hill relied only on her hands, feet, and the natural features of the rock to drive herself toward the summit.

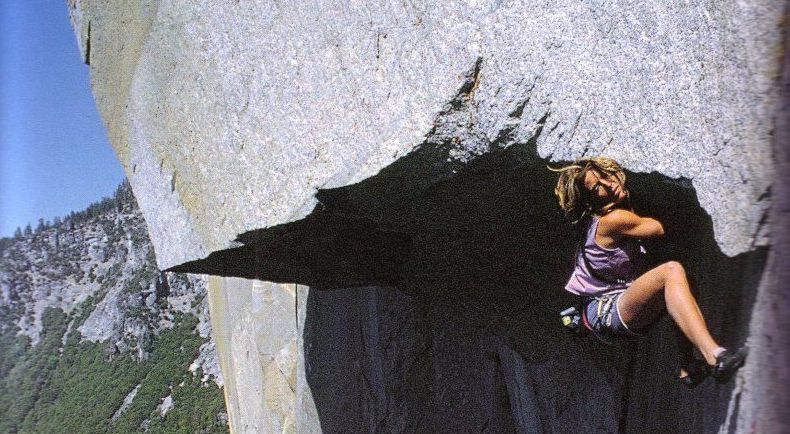

The route is composed of 31 sections—or pitches, and each presents a unique set of challenges to climbers of differing sizes, styles, and strengths. Still, some pitches, including the Great Roof, Changing Corners, and the Bolt Ladder, are universally demanding, making the Nose a formidable foe even for elite climbers.

When Hill began her first free attempt, previous climbers had already conquered most pitches. A few others, like the Great Roof and Changing Corners, were still unconquered when Hill and her climbing partner, Simon Nadin, set off in 1993. After a routine ascent of the first 21 pitches, Hill and Nadin arrived at the Great Roof.

“My foot slipped at one key point underneath the Great Roof,” Hill said in an interview with The McGill Tribune. “[But] my head was so close to the roof that it stabilized me, so I didn’t fall [….] I was able to continue and make that first free ascent of the Great Roof.”

Despite successfully completing one of the most challenging sections of the climb, Hill could not finish it that day.

“Of course, later on, on that same ascent, we ran out of food, and we were really tired, and we didn’t find a way to climb up the Changing Corners pitch,” Hill said.

Though she had free-climbed the majority of the route and performed the first free-ascent of the Great Roof, the Bolt Ladder and Changing Corners remained elusive. Together, they comprised the most difficult section, or the ‘crux’, of the route. Hill left the Yosemite Valley unsuccessful, but the Nose stayed in the back of her mind.

“I wasn’t sure that [Changing Corners] was possible to even climb,” Hill said. “Because when you look at that section of rock, it looks completely blank. And it’s not obvious how to get up something so smooth. But I […] started thinking [that] maybe it [was] possible because it’s a corner. And if it’s a corner, there’s a way to get opposition. So I just thought, theoretically, there should be a way.”

Hill returned to El Capitan with Brooke Sandahl, who had spent years figuring out the most difficult sections of the Nose. Between the two of them, they had climbed most of the difficult sections: Sandahl had mastered the Bolt Ladder, and Hill had unlocked the Great Roof—leaving only the crux to conquer.

“The real difficulty was the Changing Corners pitch, and that involved a unique blend of backstepping and arm barring and a weird move […we called] the ‘Houdini move,’” Hill said. “It’s basically one arm bar with my right arm and then another arm bar right on top with my left so that I can […] spin 180 degrees around in the corner.”

And, with that, Hill had freed the Nose.

Hill’s historic free ascent has only been repeated a handful of times since, evidence of the sheer magnitude of her accomplishment. For most non-climbers, if a climb has never been done before, then it is impossible. But for Hill, it means the next logical step.

“It was a natural evolution of my upbringing in a sport that was hardly known,” Hill said. “I was already somebody who was doing things that other people didn’t even understand [….] And once you’re involved in a sport like that and you’re on the cutting edge, you’re doing that stuff all the time. You know that nobody’s done it before. But nobody [had] come to the climb with the experience and the [mindset] that I had.”

The Nose is just one of many first ascents attributed to Hill. For her, the motivation was never competitive—instead, it came from a desire to push the limits of possibility.

“I think it comes from just the curiosity of exploring and finding out what you can do,” Hill said. “It’s very open-minded to me. Just, ‘let’s see what we can do, and put our skills together [to] find a solution.’”

Hill is always pushing people to re-evaluate what’s possible. She stands just 5’2”—and she is a woman. In the 70s, when Hill was first introduced to the sport, there were only a handful of female role models for her to look up to.

“I knew that it was unusual [for women to climb at a high level], and yet I still felt very strongly about promoting the idea of equality when prize money was different or when people would say things like, ‘Gee, I can’t even do that,’” Hill said. “Because they’re a man, they figure they should be better than me. And it was really important to me to remind people of the truth. We’re able to do amazing things as women. We can do far more than […] previous generations believed.”

Hill has inspired an entire generation of female climbers, but the benefits reach far beyond the climbing success of athletes like Margo Hayes or Ashima Shiraishi. Indeed, large-scale wall climbing can generate off-wall inspiration as well—small people armed with the pluck and determination to take on a massive sheet of granite make people feel as though their day-to-day objectives are within reach.

“I think that climbing is very positive for people,” Hill said. “I think it’s very empowering. I’ve seen how kids have gotten into climbing, and […] I think it helps them in their lives in so many other ways.”

Hill hopes that climbing’s positive influence will encourage people to be better, especially in the way that we treat the precious, colossal planet that invites curious climbers into its peaks.

“I like the idea that people, they get exposed to climbing, and […] they end up exploring places in the world that are beautiful,” Hill said. “And if we love nature, we have a better chance of saving it from destruction […] that is changing these places in ways that are irreversible.”

After all, wall climbing is a partnership. The public eye is ensnared by audacious climbers, but cliffs, crags, and boulders play an essential role, too. The rock acts as an incubator for the sport, driving innovation and creativity—and providing boundaries that are meant to be crossed.