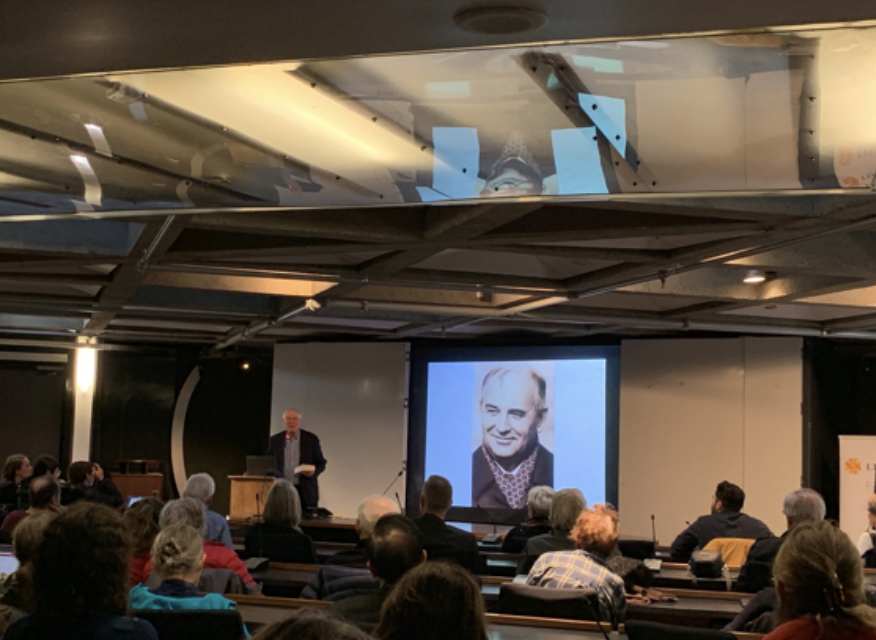

Pulitzer Prize-winning author and renowned political science professor at Amherst College Bill Taubman gave a lecture on the life of Soviet Union (USSR) leader Mikhail Gorbachev to a packed audience of McGill students and professors on Nov. 1. Drawing from his 2017 biography, Taubman presented the head of state as an idealistic, but flawed leader and suggested that his personal character was instrumental in explaining the successes and failures of the Soviet Union in its final years.

Taubman’s lecture, “The Rise and Fall of Mikhail Gorbachev—And Some Lessons for the Putin Era” was organized by the Research Group on Transitions and Global Modernities in collaboration with the Russian Studies Department at McGill.

In his introductory remarks, Taubman acknowledged that Gorbachev has had a contentious legacy, lauded abroad for his instrumental role in ending the Cold War, but fiercely criticized at home for his role in the economic collapse and dissolution of the USSR. For these reasons, Taubman said Gorbachev was a ‘tragic hero.’

“He was a hero because he laid the basis for democracy [in the USSR], conducted the first free […] elections to create the first functioning parliament, [and] ended the Cold War more than anybody else, [reducing] the threat of a nuclear holocaust,” Taubman said. “Why tragic? […] He wanted to save the Soviet Union and its new democratic form, but it collapsed, and in the process the economy crumbled, creating a […] disaster for many Soviet people.”

During his lecture, Taubman tied Gorbachev’s personal character to the successes and failures of the Soviet Union. Taubman contrasted Gorbachev’s idealistic reforms to the USSR’s staunchly inflexible governing body, the Politburo, and to a nation wary of change. He suggested that the Soviet leader’s hubris might have been the main cause of his undoing.

“How could he have thought that a country that had never known democracy for centuries could be democratized in a few short years?” Taubman said. “He was optimistic, extraordinarily so, probably excessively so. He was confident—too much so it appears in retrospect.”

For Henry Atkins, a Master’s student in political science, Taubman’s focus on Gorbachev as a person was nuanced and differed from most contemporary approaches to history, which prioritize long-term trends over the actions of important individuals.

“[It was] certainly a more sympathetic view of Gorbachev than I’m used to as a political science student,” Atkins said. “[He gave] a very agential view of history, the idea that what the person in charge does matters, [which is] not something I’m used to in [mainstream] political science models.”

However, for Sheena Li, an undergraduate student in pharmacology, the lecturer’s greater focus on character rather than on context made the topic accessible and informative.

“Since [it was] a lot about [Gorbachev’s] personality, [it was] easy for someone who doesn’t really know about [his] background to understand,” Li said.

In his concluding remarks, Taubman noted the rise of authoritarianism in Russia in recent years and his diminishing hopes for a democratic Russia. Having interviewed Gorbachev eight times for his biography, Taubman said that the former leader has had moments of optimism for his country, but that most of the time, Gorbachev has been more realistic.

“It may take the whole 21st century for Russia to find its way to democracy,” Gorbachev once told Taubman.