When news reports came out on Aug. 26 about yet another incident of sexist harassment outside the Minister of Infrastructure and Communities Catherine McKenna’s office, I felt a familiar sinking feeling in my stomach. Since I began engaging with politics in my early teen years, my awareness of gendered attacks has taken an increasingly sinister toll on my desire to pursue a career in politics. Though I know the very point of identity-based harassment is to discourage marginalized groups from pursuing politics, it is difficult not to internalize the message that you do not belong when stories of such behaviour are plastered all over every newspaper. Although there are valid critiques to be made of every politician, the line between expressing different political opinions and ad hominem attacks based on the person’s gender, race, or sexuality is often crossed, particularly as politics grow increasingly polarized.

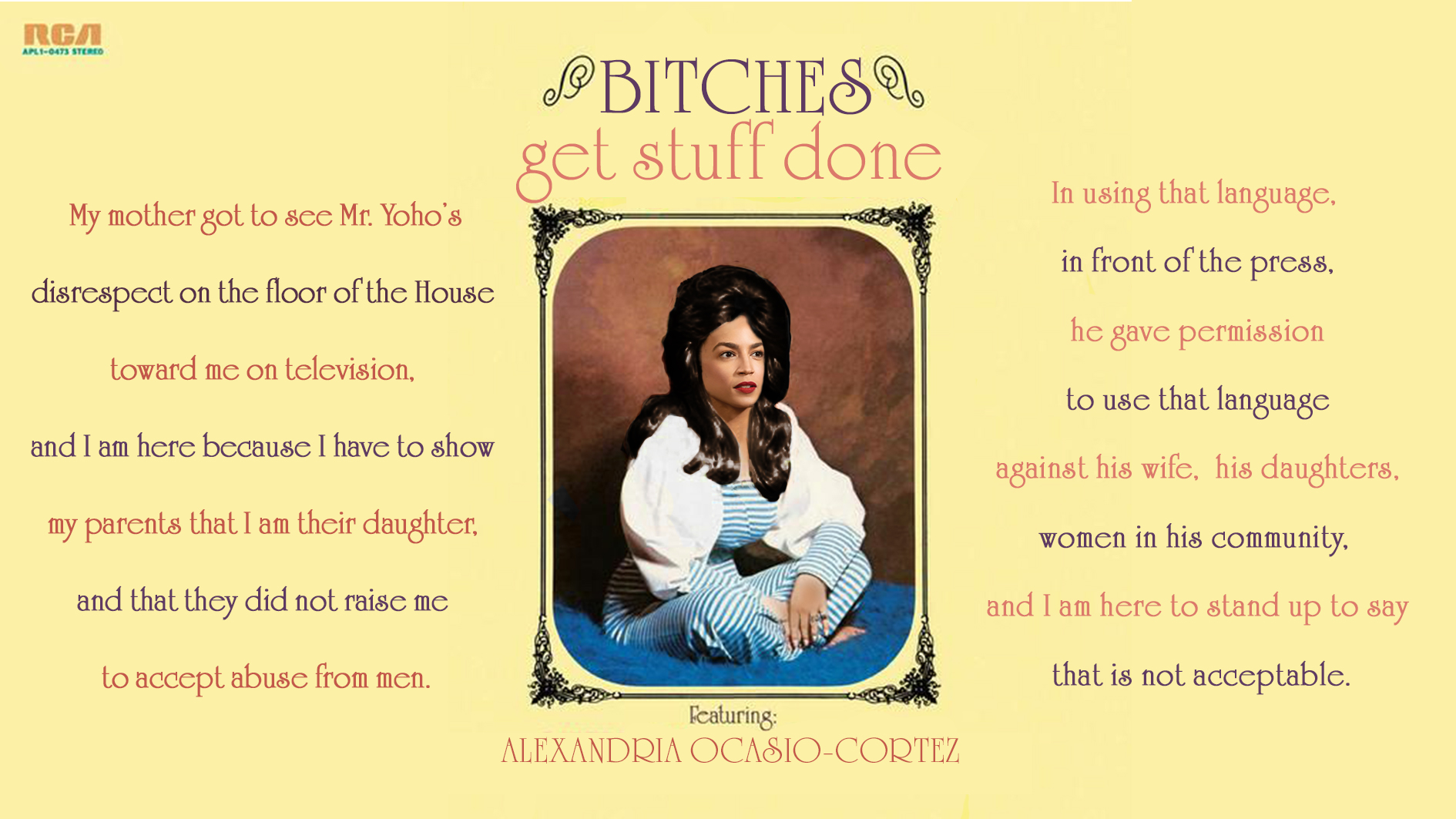

Women are three times more likely than men to be attacked online for their politics, in part due to the legal and social impunity that social media provides. While women and non-binary people in politics are less likely to be attacked physically than men in the same positions, verbal attacks are common and tend to employ gendered language. When I read articles about such attacks, like a man scrawling the word “cunt” on McKenna’s office last October, or Ted Yoho calling Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez a “fucking bitch,” I am reminded that it was not that long ago that women were excluded from politics. Perpetrators of verbal violence, intentionally or not, reinforce the conception that women do not belong in positions of power.

Women of colour and 2SLGBTQIA+ women often face hatred and vitriol far more intense than white women. These attacks are not unique to Canada: One only has to look across the border, at politicians such as Rashida Talib, Ilhan Omar, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, to see the frequency and force behind such attacks. Racialized politicians in Canada are similarly no stranger to race-based violence. Former Attorney-General Jody Wilson-Raybould was targeted with Indigenous stereotypes meant to disparage her work ethic after she resigned during the SNC-Lavalin scandal.

Politics tend to reward stereotypically masculine behaviours, such as aggressiveness, reason, and strength. When women attempt to conform to these standards, they are in violation of perceived feminine norms, and are more likely to be ridiculed by the public. On the other hand, when women are perceived as too feminine, this still inhibits their electoral success and opens them up to other lines of attack. When it comes to the way women present themselves to the public, we can’t win. Yet, our speaking styles, clothing, and mannerisms are still constantly dissected.

To young women and non-binary studying political science, like myself, the routine harassment of politicians due to their gender sends a stark message: We are not welcome in politics. Attacks based on race, gender, and sexuality are something that no one should have to bear, and their consequences are grave. Fewer women in politics, in many cases, contributes to a lack of important policies, such as access to safe abortion, childcare, and parental leave.

Criticizing politicians is fine, and an integral part of our democracy. But when civil disagreements devolve into identity-based abuse, we are actively eroding the civic ethics that are necessary for effective political discourse. While gendered comments are often seen as part of the job, especially since social media has enabled harassment of all sorts, there are no excuses for inappropriate behaviour. As the next generation of politicians, leaders, and activists, we need to take a stand against identity-based attacks and focus on what matters: The issues affecting human lives.