People often see art and science as opposing subjects––logic versus beauty, the utilitarian versus the aesthetic. Dr. Kirell Benzi, a data science researcher and data artist, does not share this view. His artwork is created from compilations of data, which he represents using shapes, colours, and movement.

On Sept. 24, Benzi presented his work during an online conference hosted by the Convergence Initiative entitled “When Data Science and Art Collide.” Leading the audience through the mysterious abstractions of his art, Benzi explained that he splits his data art into three categories based on the scientific method used to create them. The first, which he calls network art, features nodes and links amassed into enormous, colourful clouds, or twisted, sinewy shapes.

Of course, the networks are based on real data. A web of excited tweets and retweets about the 2012 discovery of the Higgs-Boson form a piece called “Scientific Euphoria,” while a vast map of performers at the Montreux Jazz Festival, classified by musical style, make up the piece “Jazz Luminaries.” Benzi explained that these visual representations help people make sense of the massive amounts of data involved.

“You want to transform complex notions, usually numbers or statistics, into something more visual,” Benzi explained. “A large portion of the brain is dedicated to vision, so it really makes sense to try to transform numbers or even text into something that we can visualize, because our brain is wired to interpret those stimuli [….] To me, when you create art, it’s interesting to have both emotion on one hand and cognition on the other hand.”

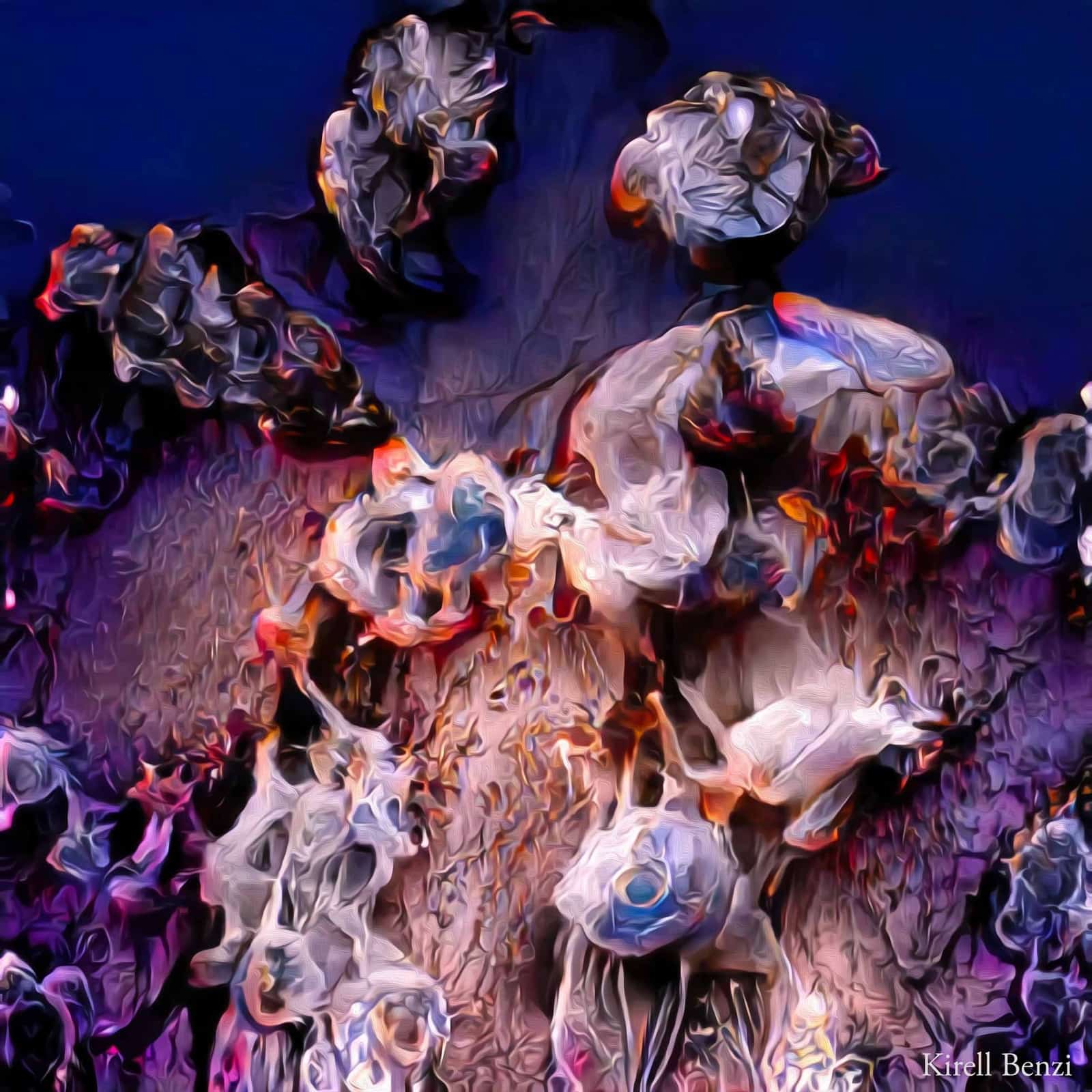

The second of Benzi’s categories is artificial intelligence (AI) art. Benzi uses neural networks, which is a way of training a computer to perform tasks by showing it a large number of examples until it can replicate that task on its own. Benzi programs his neural networks to recognize objects based on millions of different pictures and then adjusts how the network generates its own image based on all those that it previously observed. With a mix of seemingly random objects, including bubbles, wigs, geysers, balloons, and jellyfish, he creates pieces like “These Are Not Flowers,” which, while abstract, still feel oddly familiar. Benzi described AI as an artistic tool that he uses to channel his creativity.

“Sometimes, you put an ingredient in for the colour, but sometimes it’s more about the shape,” Benzi said. “And it’s very difficult to control, actually. But that’s where the artistic part comes into play because this image was not created at random. [Although] the image is created by the algorithm, [it is] a tool to put in some of your own creativity and then use it to create new shapes [….] You, as an artist, have to train the network, play with the parameters, tune them, and create the shapes.”

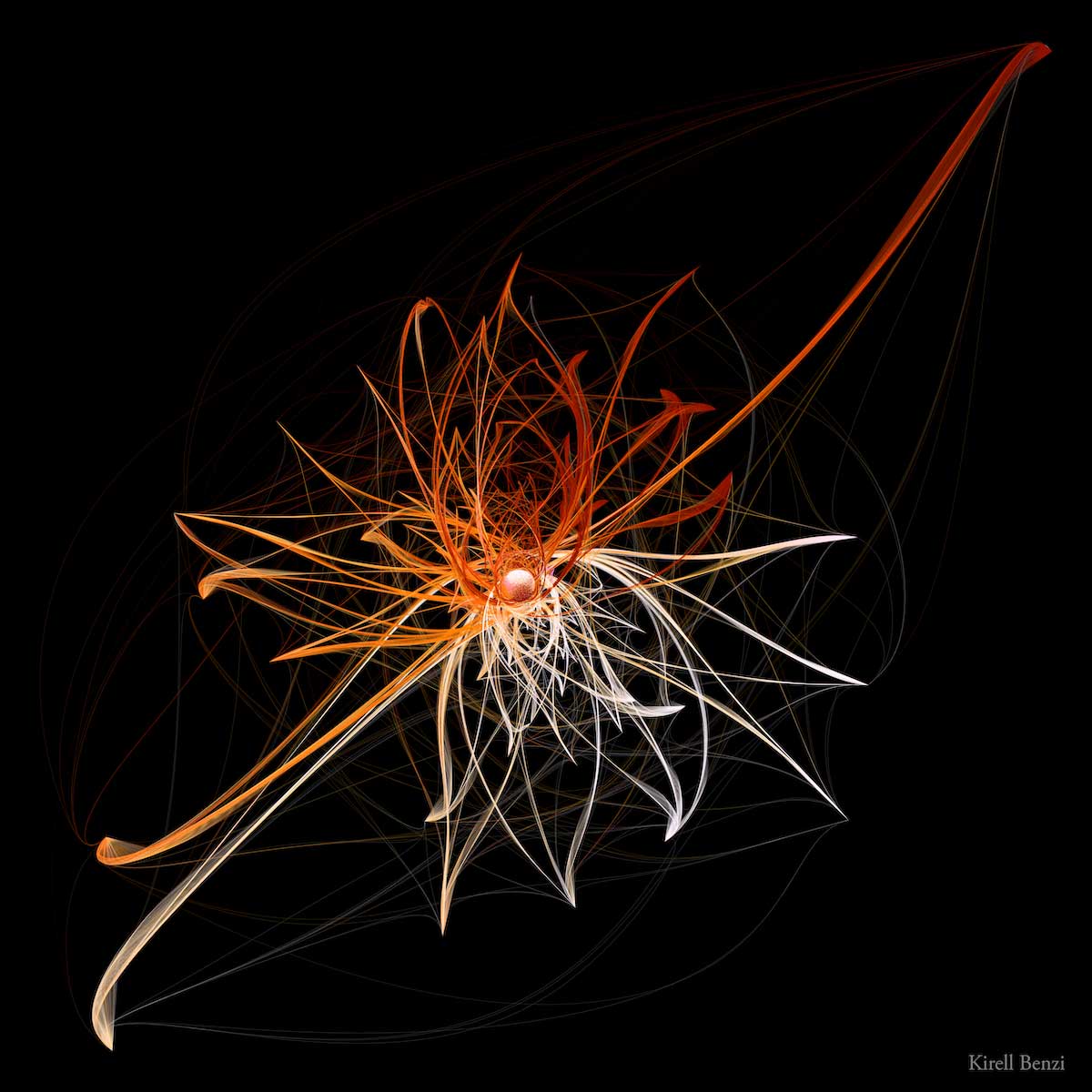

Benzi’s third category of data art is based on fractals, a mathematical and physical phenomenon of geometric patterns that repeat infinitely on different scales. These patterns make for extraordinary artwork that appears progressively more intricate as the viewer looks closer. While displaying his recent piece “Breathe,” Benzi emphasized that these fractals appear frequently in nature, and make his data artwork appear satisfyingly natural.

“If you look closely, you see that we have some repeating shapes,” Benzi said. “I really like this idea because, to me, it looks organic, maybe like a cell structure, but it’s purely math and coefficients of recurring functions.”

Benzi’s artwork fills a gap in our understanding of art and science. He adamantly seeks to teach others about the possibilities of data science, showing that algorithms can not only process data, but can also give way to emotions and self-reflection. And this doesn’t end with networks, AI, and fractals—science and art overlap all the time, even in our daily lives. It may be time to accept that the two are connected and finally look for the beauty behind the science.