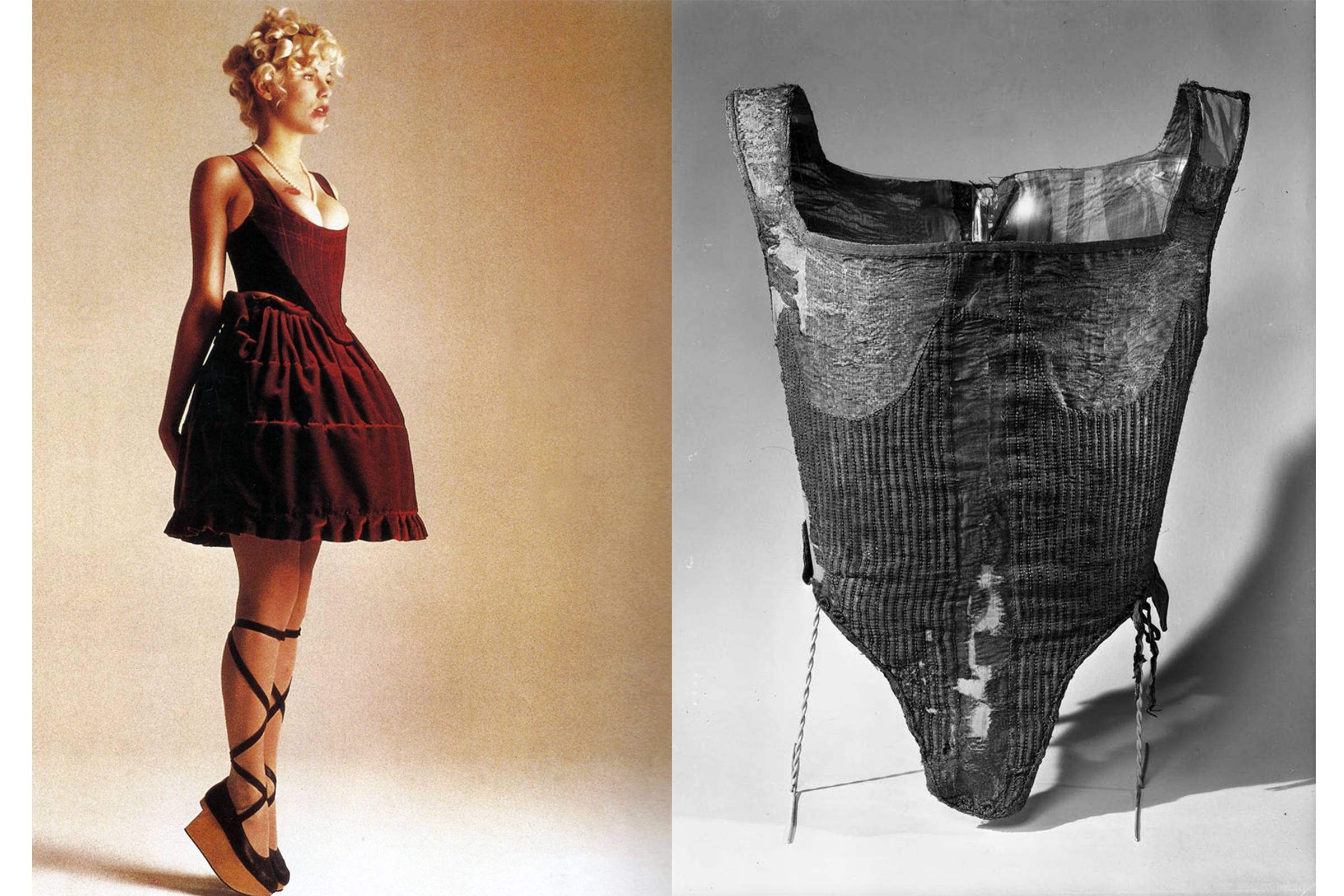

Whether you’re a Pinterest mom, an Instagram baddie, or a dedicated Vogue reader like myself, you may have noticed one article of clothing taking over celebrity fashion within the past year: The Vivienne Westwood corset. Worn by the likes of Bella Hadid, FKA Twigs, and Barbie Ferreira, the corset is a rare vintage find from Westwood’s 1980s collections. Screen printed with baroque paintings, the garment revamps a classic piece of British women’s historical costume. Corsets, however, come with concerns over health complications and a legacy of patriarchal oppression. To understand how we’ve arrived at this recent trend, it requires a look into the history of one of the most iconic and controversial garments of Western fashion.

For over four hundred years, corsets were worn to support and contort women’s bodies into the body shape that was considered ideal. In the Elizabethan era, corsets created a flat, cone-shaped torso, while in the Victorian era, corsets created a dramatic hourglass shape. The ideal silhouette of a woman was just one factor within the ever-changing fashion trends.

Catherine Bradley, Senior Academic Associate and costume designer in McGill’s English Department, noted that the comfort level of the corset-wearer depended on what kind of corset was in style—some more painful than others.

“The Victorian corset was more adverse in terms of physical effects [than the Elizabethan style],” Bradley said. “In this time period, the idea of women as physically frail, with their heaving bosoms and shortness of breath, [came] from the fact that their lungs were constrained and their waists were constricted. I think it inadvertently created this idea of the weaker sex.”

Most people likely associate the corset with such negative physical effects. In one of the most memorable moments in Pirates of the Carribean, Elizabeth Swann faints off the edge of a cliff because of a tightly cinched corset. Along with limiting lung capacity, tightly laced corsets can force organs to shift and cause muscular atrophy over time. When worn correctly, however, traditional corsets are not torturous to wear.

“It’s kind of like getting braces. At first it’s uncomfortable, but then you get used to them,” Bradley said. “I know costume designers who will wear corsets when they’re working long hours and their backs get tired; they wear them for support. And in my many years of putting actors into corsets, they seem to enjoy wearing them. Corsets change your whole physicality.“

Bradley explained that in the 18th and 19th centuries, there was a societal expectation for women to wear a corset to signal their respectability and moral righteousness. In a sense, this parallels how women are expected to wear bras today. While they do provide support, many women wear them out of a societal convention of modesty, shaping the wearer into an acceptable figure of femininity.

Today, corsets are nowhere near as rigid as the Elizabethan and Victorian ones made of whalebone and coutil. Modern corsets, like the one popularized by Vivienne Westwood, often include stretchy panels and flexible, synthetic boning, making them much more breathable and comfortable. Westwood’s design reinvented the corset by turning an upper-class undergarment into a sexy, comfortable top, offering a symbolic reclamation of women’s sexuality through a costume of the past.

The recent corset trend will not permanently disfigure you or make you faint off of a cliff. However, the history of corsets highlights an important theme of women’s fashion that continues today: Body shapes go in and out of style just like fashion trends. Instead of wearing corsets, women today are expected to achieve a perfect figure through other means, whether it be plastic surgery, intense dieting, or obsessive workout routines. Even the trend of waist-training comes with all the negative effects of corset-wearing, minus the benefits of lumbar support. Although we are far past the days of corsetry as a fashion staple, maybe we aren’t as far removed from our collective fixation on controlling women’s body shapes as we think we are.