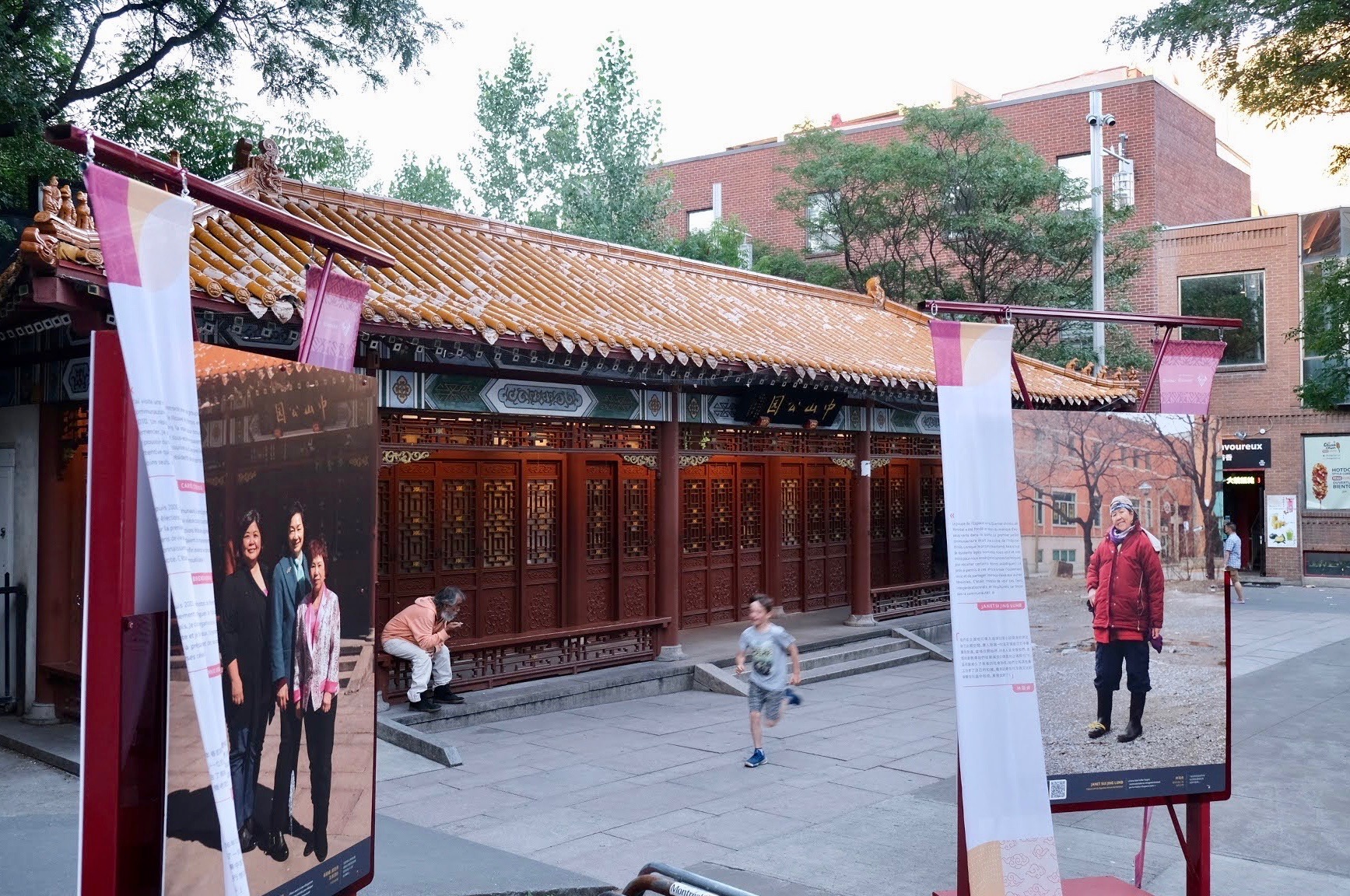

On May 26, Rue de la Gauchetière, the main street of Montreal’s Chinatown, welcomed “Dialogue with the Sino-Montreal Community,” a photo exhibition showcasing the diverse faces and experiences of its residents. Presented in partnership with the Centre des mémoires montréalaises and the Chinese Family Service of Greater Montreal, the project was initiated in a context of continuing gentrification and displacement of the Chinatown populace. Through photo modules accompanied by personal voices, the featured individuals present the often obscured cultural heritage of a storied, resilient community.

Montreal Chinatown’s 200 years of history has been repeatedly ignored by plans of large-scale real estate developments. With extensive infrastructure projects starting to invade in the 1970s, the district lacks architectural protection and has lost crucial sites of community and culture. Most recently, in January 2021, the city of Montreal approved developers’ request to acquire multiple of the most historical buildings in the neighbourhood. Parker Mah, artistic director and curator of the exhibition, sees the sanctioning of such encroachments as a neglect of Chinatown’s historical and cultural significance.

“The fact that [large-scale developments] have continued to get licensed despite all our best efforts to engage the city through the consultation process bears witness to the apathy of municipal and provincial government [toward] the tangible and intangible cultural heritage of Chinatown in Montreal,” Mah said in an interview with The McGill Tribune.

Alongside underscoring Chinatown’s architectural history, the project reveals the intangible cultural heritage rooted in the daily lives and memories of its residents. While community leaders—often Chinatown’s spokespeople in the media—perform crucial work to protect the neighbourhood, the exhibition team sought to make visible residents whose persistent service to the neighbourhood is obscured both in the community and public eye.

“We wanted to find people who come to work everyday, and run a restaurant or work as a cashier,” Mah said. “They are contributing just as much, in my mind, as [Chinatown’s] VIPs. Their sweat and blood is keeping Chinatown running through this difficult pandemic period.”

Community members featured in the exhibit, such as the owners of Chow Patisserie, one of the last places in Montreal that offered pastries hand-crafted with traditional Guangzhou techniques, or Timothy Chan, a long-time member and de facto historian of the community, bespeak the traditions and inherited expressions of culture facing erasure.

Due to language barriers, residents often face difficulty inputting their opinions in the decision-making process of Chinatown’s development. In order to meet community needs, Jerry Lan, McGill BCL ‘23 and volunteer translator with the Chinatown working group, believes there should be a greater integration of resident voices in conversations about Chinatown’s future.

“The city wants people who speak French [but] it’s hard for some of the folks who are actually in Chinatown, active in the community. ” Lan said in an interview with the Tribune. “[The language barrier] can create a dissonance in the conversation with what the community actually wants.”

The exhibition’s large photo modules, prominent along Chinatown’s busiest street, are a rare public commemoration of Chinese identity for the neighbourhood. While wedged between the heavily saturated cultural sites of Old Montreal and Quartier des Spectacles, Chinatown itself receives few forms of cultural investment. Mah described how the exhibition creates a sense of pride among community members who may, in differing ways, identify and celebrate themselves with the displayed stories.

“It’s pride for them,” Mah said. “Not just for the people in the exhibition but for the people who live in the area to see that something’s being done, that your face and people are being put forward and recognized.”

The exhibition’s guided tours, offered on several dates between June 16 and 27, aim to share and spur discussions with the public on Chinatown’s histories. Led by youth volunteers, the tours allow younger generations to continue preserving Chinatown’s culture and heritage.

“[The tour animators] are not experts in Chinatown’s history, but are there to engage in dialogue with visitors about their experiences as young people growing up in Chinatown,” Mah said. “It’s really about opening up conversation.”

The exhibition will be on display until October 15, 2021.