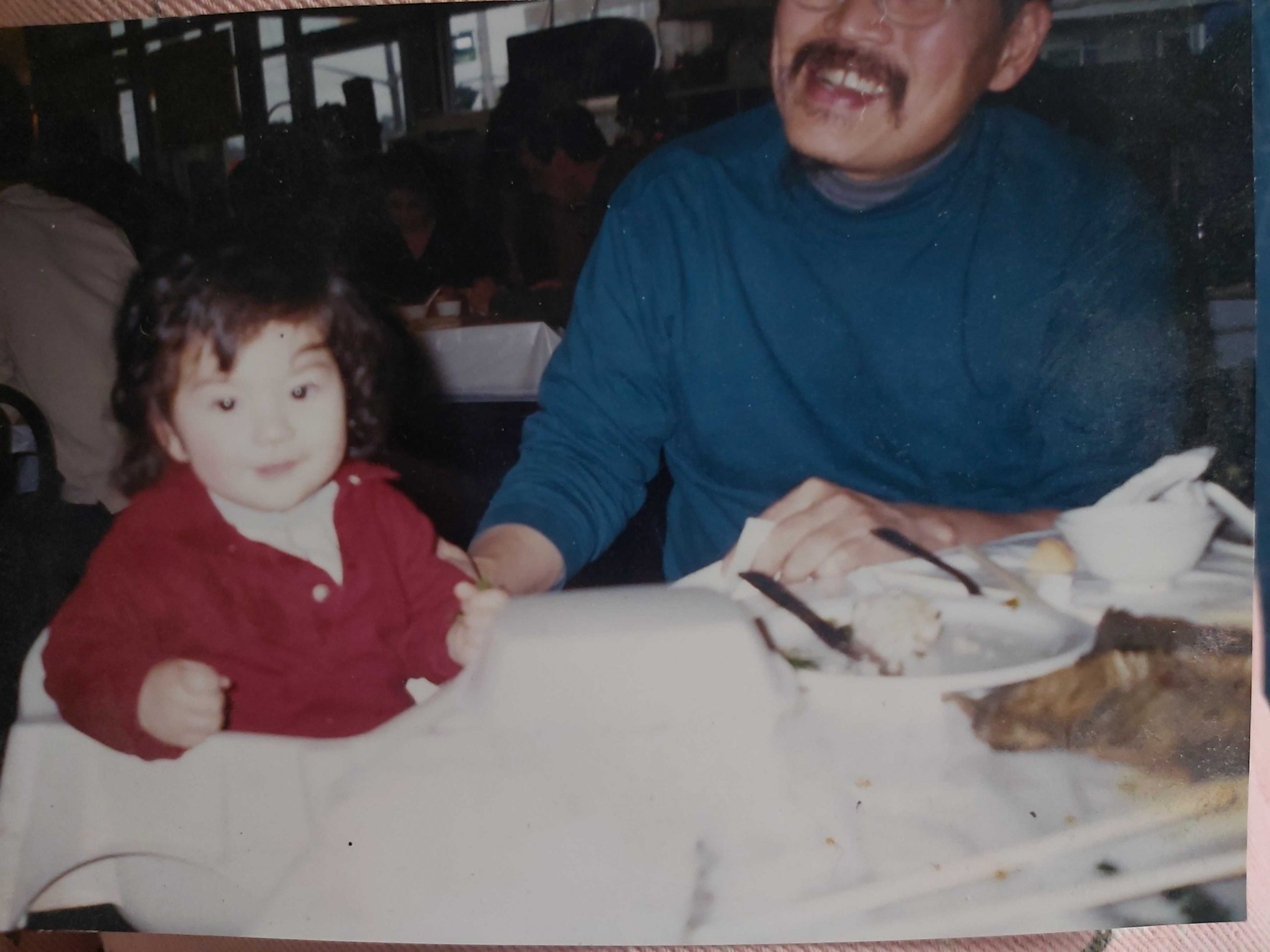

It took me until I was 12 to realize that my father’s English was accented. Before that, it was just my father’s voice: Familiar and melodic, a vestige of his first, tonal language. Like many mixed kids, I was hyper-aware of the racial categories I fit into from a young age. While I often wondered if I looked more white or Chinese, language did not play a part in my identity struggles. At home, we spoke English, and my highly educated father was always able to express himself in his second tongue.

Things changed when my parents decided to move to Taichung for my mother’s sabbatical. While she researched Taiwan’s forests with my father as an ad hoc translator, my world turned upside down. At school, I fought through tears as teachers and classmates attempted to engage me in a language I had never learned. My only allies at school were two Taiwanese girls who knew some English. When I tried to speak Mandarin one time, my friends laughed at my accent. I realized that while I felt somewhat Chinese at home, in Taiwan, I was completely foreign—seen as white as it gets.

We returned to Canada less than half a year later, but my feelings of linguistic inadequacy stuck with me. In the eight years afterwards, I took Chinese lessons with my mother. My accent sounded more natural by high school, enough to be taken for a native speaker—as long as I managed to spit out a few confident sentences. When I was 16, I went to Shanghai with my dad, spending my days in his air-conditioned office wrestling through articles on Baidu, the Chinese equivalent of Wikipedia.

Although I was half-literate by the end of summer, I was still unable to fully grasp the language. I had learned Pinyin, the standard romanization of Chinese; I had encountered a few thousand characters; I even occasionally dreamed in Mandarin. But nothing ever translated to spoken fluency—probably because I never had anyone to speak to. My father has refused to speak Chinese with me throughout my life, citing his own discomfort using the language, even though he uses it with others. I began to wonder if I’d ever be good enough.

The fall after I returned home from Shanghai, I gave up learning Chinese. I spent my Fridays watching movies with my friends instead of studying grammar particles. There are times when my decaying comprehension of Chinese feels like a wound. But in truth, ending my studies was a huge relief. I stopped feeling that I had to prove my Chinese identity to myself, or make up for a childhood of linguistic immersion I never had. I also began to question the exclusionary paradigm that I implicitly accepted—that identity hinged on a certain grasp of language or a kind of invisible flexibility across cultural spheres. It wasn’t just me who was excluded by this linguistic absolutism, but others as well, like transracial adoptees raised by white families, or native speakers who experienced first language attrition.

In truth, cultural identities are transitive and expansive, shifting across geographical context. Some diasporic individuals who return home even experience “reverse culture shock,” where familiar elements of their native country seem alien. My father often confesses to me that he has issues understanding modern Mandarin, with its English loan words, Tiktok slang, and novel technological terms that did not exist in 1960s Taiwan. As for myself, to accept that I’m the product of my circumstances, to integrate poorly into one of my cultures—this is a tough thing to face. But it’s also what most new immigrants confront when they try to integrate into a new country.

My father once explained to me that he learned English by slowly reading books with the help of a Chinese-English dictionary, and I told him I couldn’t imagine learning another language without the internet. Only years later did I understand his response: “There was no other option. I had to survive.”