Growing up, I never had chicken nuggets or frozen pizza for dinner. Instead, there was a fresh, home-cooked Persian meal in front of me each night––and looking back, I was extremely unappreciative of it. As I have gotten older, I have grown to appreciate that the love of somebody labouring for twelve hours to make your favourite dish is not a feeling that everybody gets to experience, at least not on a regular basis. As silly as it may sound, understanding the love languages of those around you is vital to healthy relationships. It was through this newfound appreciation for the many different ways of showing affection that I began to value all the little things my dad did for me growing up—even if it just started with a stew.

When I was a kid I was a picky eater and somebody who did not understand that different cultures come with different foods. I truly thought that my parents were villains for not letting me have mozzarella sticks for dinner like many of my peers did. When I was served an intricate Persian meal, I would promptly complain and ask for spaghetti. But this never stopped my family from showing their love in the way they do best, and that is how Persian spaghetti entered our home. A combination of Canadian and Persian food that had spaghetti and meat sauce but also incorporated potato tahdig—an addition that my sister and I would fight over—it became a dish my dad made often.

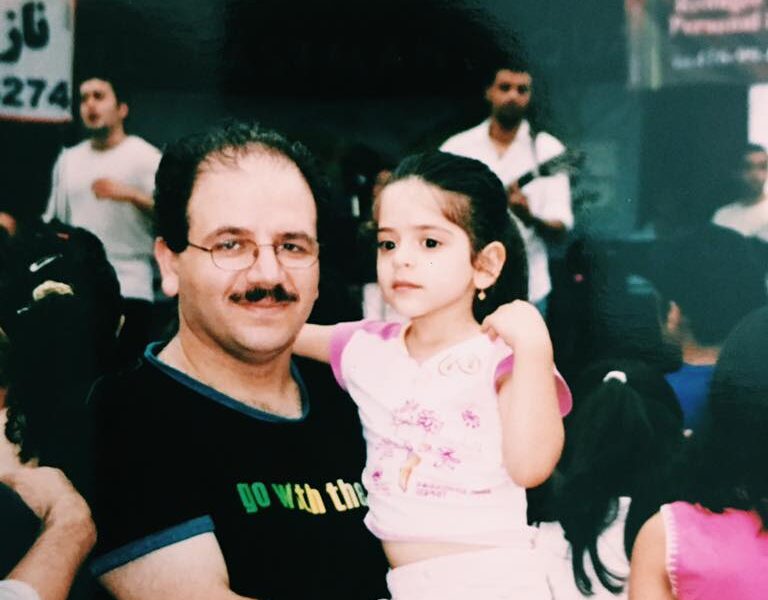

My dad is the epitome of what you would call “a man of few words.” You can tell him a 20-minute-long story, and while he will pay careful attention the whole time, there is a good chance that the only response you will get is a nod. When I was younger this would frustrate me; all I wanted was some kind of conversation. But as I have grown older, I have learned to appreciate the way that he shows his love. To put it in terms that my father would not fully understand: His love language is definitely ‘acts of service,’ and cooking allows him to express his love for our family.

A lot changed as I grew up, but the quality and the love that went into the food I ate remained consistent. Even when our family shrank from four members to three after my parents’ divorce, and then three to two when my sister went to university, my dad would spend hours cooking. I did not understand why he spent so much time in the kitchen after a long day at work when it was just us two. Drawing on what I saw from my peers around me, at Thanksgiving and Christmas feasts, I thought that me and my dad at the dinner table, re-watching Gilmore Girls, was not exactly the right occasion for sabzi polo. But my dad does not need an audience. He just needs one person that he loves at the table, and he is happy to spend 10 hours over the stove, making sure that everything is perfect.

Although it sometimes saddens me that I failed to fully appreciate what it meant when my dad would pull out estamboli on a random Thursday night when I lived with him, I know that to him, seeing me hastily finish the food on my plate was more than enough. On the train to my dads, my sister and I talk over what we want to eat at home. I know her go-to is ghormeh sabzi, an herb stew, and mine is always fesenjoon, a pomegranate and walnut stew that takes all day to make. When we get into my dad’s car, we both know that his first question will be, “what dishes do you two want this weekend?”