On Jan. 20, Max Liboiron led a webinar on “Building feminist and anticolonial technologies in compromised spaces” as a part of the fourth season of the Feminist and Accessible Publishing and Communications Technologies Speaker and Workshop Series. Co-sponsored by Alex Ketchum, a faculty lecturer at the McGill Institute for Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies (IGSF), and Concordia University professor Damon Matthews, the webinar detailed how to navigate work in sites tainted by strong histories of colonialism—and ultimately, how to achieve structural change.

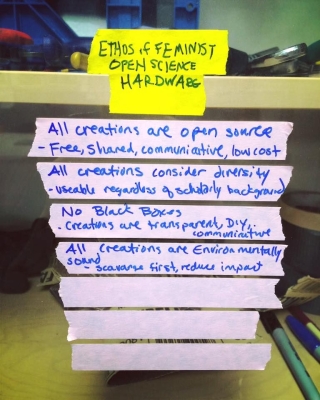

Liboiron, an associate professor in geography at Memorial University and formerly the school’s Associate Vice-President of Indigenous Research, is Métis and a leader in developing and promoting anticolonial research methods across disciplines. As the founder of the Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR), an interdisciplinary plastic pollution laboratory that operates out of Memorial University, Liboiron has shaped public policy on both plastics and Indigenous research.

During the webinar, Liboiron discussed the concept of “compromise”—not as a failure, as some proponents of institutional change might see it, but as a condition of doing ethical work within uneven power relations. They highlighted the necessity of establishing equitable research methods and policies within colonial systems and institutions.

According to Liboiron, even in the process of decolonization, individuals will inevitably reproduce parts of colonialism due to its pervasiveness.

“When I’m talking about compromise and reproducing parts of the system that we are trying to change, it’s the condition of doing the thing. It is the condition for making change,” Liboiron said. “You don’t get to start from somewhere else, there isn’t somewhere else, this is the place, and that is the basis of your collaboration in the world.”

Liboiron also highlighted the role infrastructures play in upholding and defining colonial spaces and institutions. They explained that within the research sphere, structural power difference between Indigenous communities and universities is often downplayed; in practice, university researchers, rather than Indigenous people, often stand to gain the most from data collected on Indigenous communities. Thus, one of the key ways to decolonize research and combat unequal power dynamics, Liboiron explained, is to establish data agreements that empower Indigenous communities to own their own data.

“Indigenous data sovereignty is about how and why they need to own and control their data,” Liboiron said. “A sovereignty model for a research collaboration with an Indigenous group can be that the Indigenous groups decide the priorities, the overarching ethics and goals of the research, but then I as the researcher ‘fuck off’ and do the work. That’s the recognition of unevenness and of owning your place in the uneven infrastructure.”

Ketchum, writing to The McGill Tribune by email after the talk, said she feels inspired by Liboiron’s recent book, Pollution is Colonialism, and is motivated to bring anticolonial scholarship into the classroom.

“Dr. Liboiron thinks critically about university structures, lab structures, and research practices,” Ketchum said. “I’ve loved being able to assign Liboiron’s work in the GSFS feminist research methods courses that I teach, because their work helps students and researchers question what it means to do feminist and anticolonial research.”

Matthews, a professor, research chair of climate science and sustainability at Concordia, and director of the Leadership in Environmental and Digital Innovation for Sustainability (LEADS) program, hopes universities will use their influence to promote social and environmental sustainability.

“I really appreciate the idea that we can work toward achieving transformative change while also acknowledging the flawed nature of many of the institutions that we operate within,” Matthews said. “But, as institutions, few universities have succeeded in challenging the power structures that propagate the fundamental inequalities and injustices that could undermine our sustainability goals.”