When I looked down the barrel of the microscope, I could see everything.

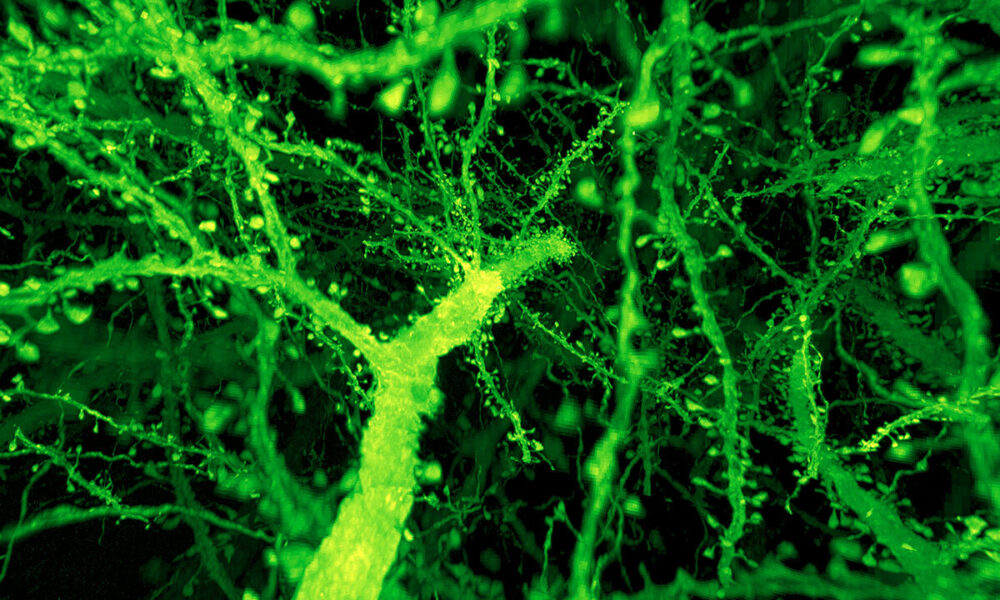

I saw exploding galaxies of green fluorescence, and a network of nebulas dotting a dark, surrounding infinity. I saw the edge of a coastline studded with city lights, and islands surrounded by swirling oceans, like I was peering down from the stratosphere.

What I was really looking at were the dopamine terminals of neurons, stained with a green fluorescent antibody. Truth was, I was just at work, having a spiritual experience in a dark, stuffy room in Stewart Biology. I was lucky enough to be looking at a slice of bird brain, helping out on a research project about how zebra finches perceive mate calls.

Moments like this are rare in scientific research, but their thrill is unparalleled. Most lab work, whether it’s data entry or making solutions, feels tedious or very, very complicated. And nothing ever goes the way you expect it will. It’s hard to see how the daily grind fits into the grander scheme of discovery.

Scientific research has inherent value beyond professional merit and academic citations. Getting to do research is a privilege that should be presented as an opportunity to learn something new about the world around us, not just as the next rung up the ladder of a science education.

But the world of academic publishing is a cutthroat community. The dogma of “publish or perish” haunts academics at every step of their careers, from getting into grad school to securing tenure as a seasoned principal investigator (PI). At a research-oriented, highly competitive university such as McGill, undergraduates are often susceptible to approaching science as a game they want to win. And too often, the beauty of discovery is left behind as a pretty fantasy, a child’s eureka.

But what might be lost when the new generation of scientists are trained through tests and checkpoints? Science education erects barriers of interest to weed students out starting as early as grade school, where evaluation styles are primarily timed and memorization-based. For kids that don’t perform well under these conditions, they are made to feel like math and science aren’t “for them”, and any curiosity is replaced by anxious aversion. Those that choose to pursue it are conditioned to enter a system that rewards quantity over quality.

The relentless approach of prioritizing publications over all else creates problems that marr even the most sacred of scientific disciplines. A recent exposé published in Science News casts doubt on findings from a seminal research paper on Alzheimer’s. Allegedly, image tampering had been used to inform an entire field and to fund it, too. What would lead a researcher, in a field that deals so intimately with people’s integrity, to fabricate data?

The answer is a Darwinian system, where funding agencies, the government, and universities are the ones creating the selective pressure. And the less funding a lab has, the more difficult it is to produce quality research, to publish good papers, and to earn a living. The laws of supply and demand dictate just how merciless the competition becomes—the more research labs applying for grants, the less funding to go around. All of this squeezes the energy out of scientists, thus reinforcing institutional barriers that keep low-income and racialized researchers out of the game. People who have to work multiple jobs and juggle childcare responsibilities can’t be expected to maintain the same productivity level, and their careers suffer for it.

An obvious fix would be to inject more money into basic research. Another option would be to reexamine how faculties set up tenure applications, which are inordinately based on citation number, and instead consider how a professor inspires the next generation of students to love what they are studying.

When I decided not to pursue research in graduate school, I asked myself why I was continuing to work at a lab. Other than perks like friendships and good management, there is joy in science for science’s sake. And there is comfort in knowing that, should I publish, my paper would assume its rightful place as a drop in the ocean of discovery.

Pingback: Representation, not impersonation - The McGill Tribune