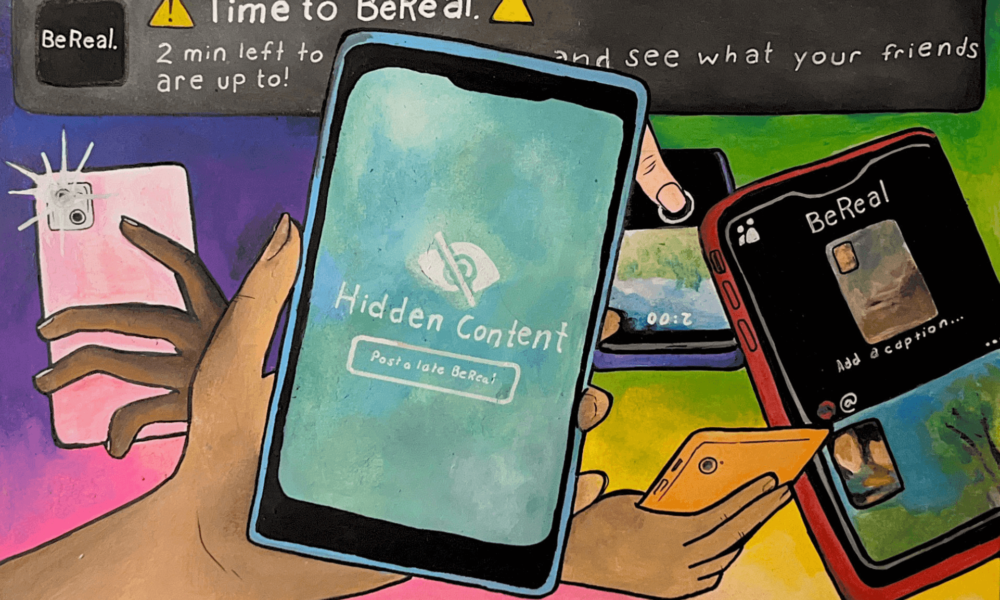

Many students across North American university campuses receive identical notifications on their smartphones every day: Time to BeReal. The alert is sent out to all those who have downloaded the popular social media app BeReal, which delivers a less-filtered online experience to those looking to avoid overly-polished content. The recent rise in the app’s popularity has sparked some buzz among Gen Z—most notably, university students—and has reignited interest in the psychological effects of apps designed to document our lives.

BeReal sends users a daily notification at a randomized time of day, prompting them to simultaneously capture an image of themselves and their surroundings within two minutes of receiving the notification. Users’ photos are posted to their pages for their followers to enjoy. The app is meant to be all that Instagram and TikTok are not: Unfiltered, organic, and spontaneous. In other words, the BeReal app is an interface meant to offer its users the opportunity to connect with one another’s authentic and real-life content. Its popularity, however, may not be due to the kind of interactions it offers between users.

Many organizations, such as the Canadian Mental Health Association of Ontario, consider social media and excessive internet use to be an addiction. People addicted to social media experience many of the symptoms seen in other types of addictions, such as drug and alcohol dependencies, including mood changes, increased tolerance with use, and even withdrawal and relapse symptoms.

According to several neuropsychology studies that examined the effects of long-term social media use on chemical interactions in the brain, the neural pathways activated while scrolling through platforms like Facebook or Instagram are the same as those when using cocaine. Many of these pathways involve dopamine, a neurotransmitter and a hormone that generates the pleasurable reward feeling we get when we gamble or take an addictive substance. Big social media corporations are well aware of this and exploit the brain’s craving for larger doses of pleasure. They do all that they can to keep users consuming content, like incorporating a refresh feature to increase session times. The longer you spend on social media, the more addictive it becomes, and the more your happiness depends on it.

In spite of BeReal’s claims that it provides a “realer” form of social media, users may find themselves trapped by the same addictive mechanisms used by Facebook and Instagram.

“Requiring people to post at a particular time really doesn’t solve any of the problems of online interaction, and it intensifies pressure on people to represent themselves,” wrote Jonathan Sterne, a professor in McGill’s Department of Art History and Communication Studies, in an email to The McGill Tribune.

For some, BeReal’s spontaneous notification is indeed an added stress, but its promise of authenticity is a huge plus in many users’ eyes. It remains to be seen whether the app is less addictive because, unlike other forms of social media, the whole experience is very short-lived.

“I like the idea and I think it’s fun but other than the one photo you take a day there’s really nothing much else to it,” wrote Kate Frost, U3 Biology, in an email to the Tribune. “It’s interesting for about five minutes a day at most.”

For some McGillians, BeReal is new, exciting, and fun. For others, the hype is over. Social media giants like Meta and Twitter, however, are harder to escape. When new apps enter the zeitgeist, it’s important to be critical of the claims they make. Maybe BeReal’s nostalgic return to authentic social media is necessary. But, if our psychological tendency to use social media apps for comparison is any indication, that’s a big maybe.