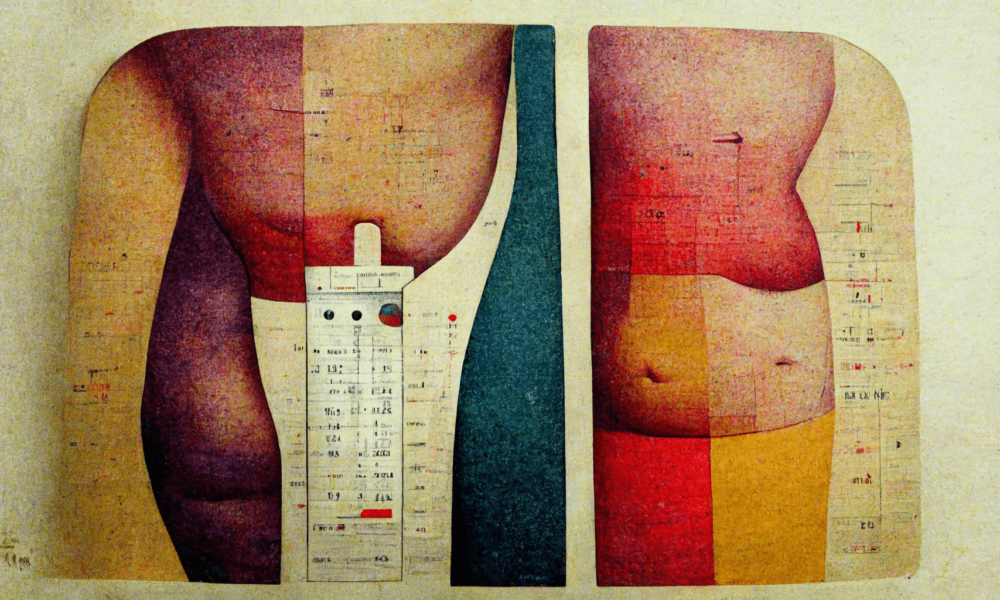

Imagine a medical assessment tool that tells you about a patient’s body composition—a tool that is used to determine levels of disease risk, dosages for vital medications, and individualized treatment plans.

Now imagine this tool was based on the body measurements of white European adult men, but is applied the same way regardless of gender, age, or ethnicity. Imagine this tool’s accuracy and usefulness were never established with the scientific method. Imagine that the interpretation of its results has been called out as misleading, if not medically dangerous. Would you still trust this tool as an essential part of general health care?

This is the story of the body mass index (BMI). Still an official measurement tool for physicians according to the “Canadian Guidelines for Body Weight Classification in Adults,” the BMI is widely used across North America and beyond. Weight in kilograms is divided by height in metres-squared to generate a ratio that automatically classifies an individual as underweight, normal, obese, or morbidly obese. A BMI of 18.5–25 falls within the “normal range”, while anything beyond that is considered overweight and “puts you at increased risk of developing health problems,” according to the Quebec government. Nothing is stated about the health problems associated with a lower-than-normal BMI—the implication is that there are none.

The glaring problem, of course, is that the BMI does not take muscle mass or per cent body fat into account. Instead, the seemingly neutral measurement tool is used to classify patients as “obese” without considering how a “normal range” differs from person to person. The BMI is still the singular metric used to calculate nationwide obesity statistics, with no other supporting data.

To understand the inherent flaws associated with the body mass index, we must rewind to the 1830s. Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet was trying to develop population-wide body standards based on the “average man” (read: French and Scottish soldiers) in order to find the population mean, which he considered the social ideal. In fact, it was later used as fodder for the eugenics movement to sterilize disabled people, fat people, and racialized people. Quetelet’s Index, as it was called, was never supposed to be an individualized measure of body composition.

For years, social health advocates and fat activists have decried the BMI, but it seems that these waves have barely disturbed the widespread practice for reasons perhaps generational, likely institutional, and undeniably racist. The BMI completely ignores the social determinants of health, especially race and income, which are inextricably linked. Inuit in northern Quebec are already less likely to have access to nutritious, affordable food due to systemic policy failures, yet the BMI ignores this and overestimates the health risk of obesity in this population.

It’s a double-edged sword of neglect—non-Indigenous health care workers may be focusing on a so-called “obesity epidemic” in this population at the expense of the very real food insecurity epidemic. The BMI is yet another example of a colonial practice being forced on Indigenous peoples to their detriment, while traditional knowledges of health care are largely ignored.

The uncritical application of the BMI, then, is actively harming our health. Many people with a high BMI are perfectly healthy—think of those with high muscle mass, higher bone density, and those with low metabolisms—but are still subject to health recommendations such as restrictive diets, or being told that they are at higher risk of disease when they are not. The world of medical research is shockingly fatphobic, and the stigma associated with bigger bodies causes weight shame and discrimination. In turn, this leads to the avoidance of medical treatment and poorer mental and physical health outcomes.

One of the most esteemed principles of science is that correlation does not imply causation. The correlation between a high BMI, an inherently flawed measure, and the risk of diseases such as diabetes or heart disease, is just that—a correlation. The true causal link that public health should be investigating is the relationship between fatphobic, outdated tools of assessment and inadequate health care.

Pingback: The Disadvantages of Transformation Diets – trading4u