Many undergraduate students desire to delve into research at McGill in labs led by primary investigators and professors. Undergraduates themselves, however, have equally promising initiatives to lead exciting investigations. One of these student groups, McGill iGEM, is an undergraduate synthetic biology research team that has made impressive progress in recent years.

In an interview with The Tribune, Jonas Lehar, U2 Science and lead of iGEM’s wet lab— the group that performs hands-on lab procedures—discussed the club’s projects and gave insights into the club’s mission.

“The way I like to describe [iGEM] to people is [that] it’s a science fair for big kids,” Lehar shared. “We come up with a project over the course of the school year, and we spend the summer doing the research in the lab. Then we present our research at the International iGEM conference in November [in Paris].”

This year, the team will be presenting its cancer therapeutics project. As Lehar explained, many existing cancer drugs target mutated proteins that cause the cancer to grow and spread. Such a treatment, however, also targets healthy cells, which causes the side effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

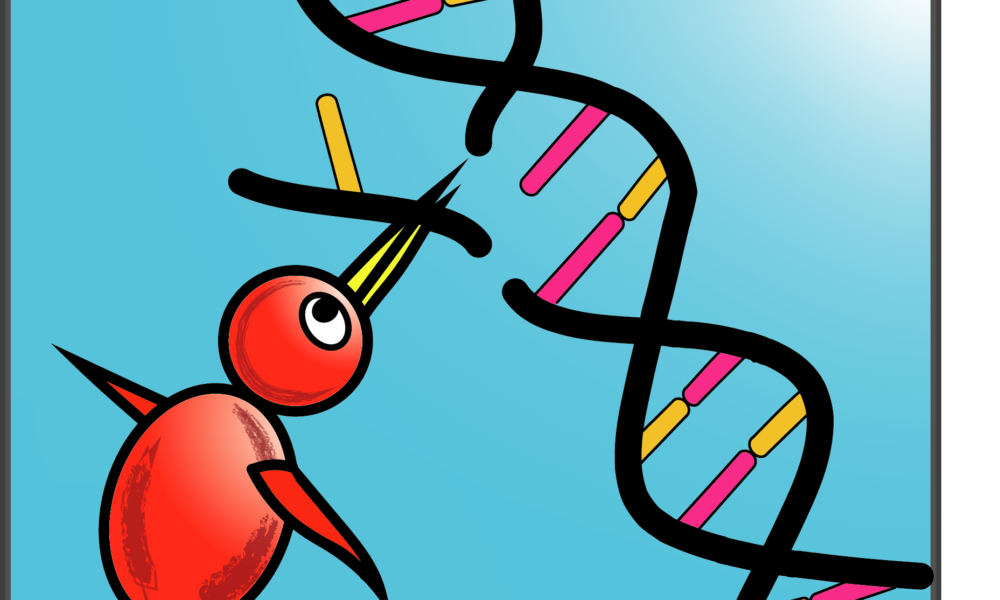

“We decided to try a [different] approach to cancer: Instead of trying to target the mutated proteins, we could target the DNA directly,” Lehar explained. “What fundamentally [causes] cancer are mutations in the DNA, so instead of targeting the proteins we could target cancer at the genomic level directly. This way would avoid targeting any healthy tissue.”

The team targeted messenger RNA (mRNA)—a complementary copy of DNA that is used to synthesize proteins. The team introduced several new elements into their test cells: Cas7-11 protein, guide RNA, CSX29 protease, and a fusion protein. This is an application of the new generation genome-editing technology known as CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats).

Cas7-11 protein works in tandem with guide RNA—a type of RNA sequence that recognizes cancer-causing mutations in the mRNA. Once guide RNA finds one of these mutations, Cas7-11 activates CSX29 protease. The protease cuts and thereby activates the fusion protein, which creates pores in the cell membrane and causes cytoplasm leakage. Not only does this kill cancerous cells, but it also stimulates the immune system.

While this is an impressive result, it is important to note that the team’s research is all in vitro—in the tube—and has not been tested in vivo—in animals.

“We’re not testing [this system] on cancerous mice models because we don’t have funding for it—lab mice are very expensive. It’s also not possible within the year timeframe of the project,” Lehar explained. “However, team members from the previous years often do decide to continue the project that they worked on, so [testing our model in vivo] is definitely something we’re looking at in the future.”

The McGill iGEM will be recruiting new members in Winter 2024 for SynBio collective, STEMcast and InVitro Conference. They are looking for students from a variety of science programs, including Microbiology and Immunology, Anatomy and Cell Biology, Neuroscience, Bioengineering, Biochemistry, and Computer Science. This is part of their attempt to expand iGEM into a broader community of students and future researchers.

“In the past, iGEM was a small group of passionate students who wanted to do research. But [now] we’re trying to turn iGEM into something larger, something where we can get more students involved than just the competitive team,” Lehar said.

Last school year, iGEM also organized synthetic biology workshops to teach students lab techniques and provide them with experience similar to that of a formal McGill lab course. They also ran a workshop for the Shad summer program in Montreal for high school students.

“The idea of iGEM is that we want to make an opportunity for students to get in [a lab], to take a project and work on it from start all the way until the end. It’s really hard to get that first lab experience that you need to get started somewhere,” Lehar said. “A lot of profs want people who already have prior experience. We want to [be] a stepping stone for people to spark their curiosity in synthetic biology, and also encourage their scientific careers as they go on.”