Elegant script, frayed edges, the occasional hole, and sketches of the man himself. Letters signed Voltaire, V, or—occasionally—Volt.

Université de Sherbrooke professor Peter Lambert-David Southam has gifted McGill a stunning manuscript collection of 290 documents including handwritten letters, correspondences, and fragments of Voltaire’s work. Curated by Ann-Marie Holland in collaboration with professor Nicholas Cronk and digitized by faculty and students at the Université de Sherbrooke, these documents allow us to gaze into Voltaire’s life—particularly his time at the Château de Ferney. Four generations of Southam’s family lived in the Château after Voltaire, which is how the collection was assembled and brought to Québec.

As Cronk noted during his lecture on Oct. 28, “The McGill Library has now become one of the world’s major centres for the study of Voltaire.”

But why care about manuscripts today? Cronk made a case in his lecture.

An 1841 letter has “Open Cautiously” written on the envelope. “Mr. Reed, who lives in Leeds” sent a letter to novelist Maria Edgeworth, begging for a signature. She wrote back with a signed reply—written on the inside of the envelope, knowing that if he ripped it open in his enthusiasm, he would destroy the signature.

An Ariosto manuscript at the Biblioteca Ariostea is smudged at the bottom. Over 200 years after its writing, Alfieri visited and loved the manuscript so much, he signed it like a visitor’s book (generally frowned upon today, but the librarians made an exception for Alfieri). He cried, smudging the ink.

These remnants let us see a different side of the author’s life, one unpublished, uncirculated, unremembered. Authors are often so much more than what they publish—we go far beyond the selves we choose to present to the world.

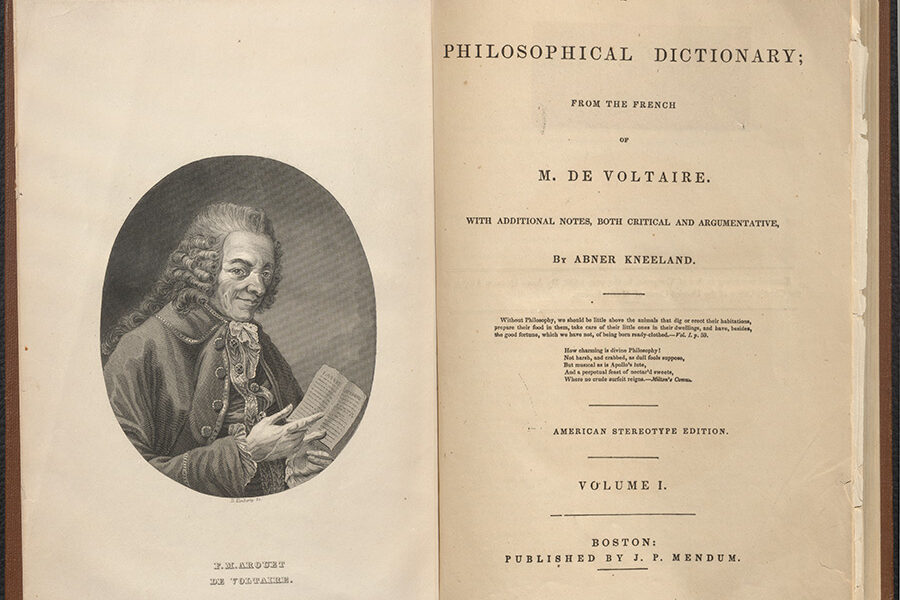

Voltaire—whose given name was François-Marie Arouet—was an enormous celebrity as well as an amusing character in his time. He won the lottery multiple times—but not through luck. He and a group of friends discovered that the prize fund exceeded the cost of each ticket. So they proceeded to divide and conquer: Buy every single ticket, split the profits, laugh at the authorities, repeat. But what about the parts of his life that society didn’t see?

“In the French sphere, we’re all familiar with those writers mainly in the 19th through 20th centuries: Flaubert, Proust, Valéry, who kept enormous numbers of manuscripts, they kept all their work in drafts… Sadly—or maybe happily—you can’t do that for Voltaire,” Cronk said.

There are exceptions. A famous scene in Candide involves the titular character encountering an escaped enslaved person. He sobs. A manuscript was found in the 1950s, written the year before publication. This scene isn’t there—it was added later.

The Collection allows us to connect with a different side of Voltaire. These are letters he wrote to friends, fans, and loved ones (Voltaire often gave his work to “women admirers”). There are holes. No margins. Cheap paper. But we can also see the inverse: Instances of extreme formality, almost forced and very funny.

Voltaire wrote a letter to the (extremely Catholic) Queen of France seeking her approval of La Henriade (an epic poem criticizing the Catholic Church). The letter-writing convention of the time indicated that the more space left after the address, the more respect for the receiver. He left nearly a full page of space. She never answered.

The Collection offers incredible insight into Voltaire’s later years: Who he was writing to, what he was writing, how. Strings of poetry, history, fun, official correspondences, and mistresses weave a tapestry of not only his essence as a person and author, but his everyday life.

Fragments of quotidian life allow us to connect with the past on another level. These documents bring us to the fantastic—but also disconcerting—conclusion that authors are everyday people as well.

Selected works from the collection can be viewed in the ROAAr Reading Room without appointment from Mon.-Thurs., 10 a.m.-6 p.m. with a piece of government or student ID.