“If you were to walk around any undergraduate large lecture hall and be a fly on the wall, how many students do you think would have something unrelated to the course material open on their screen?” Aaron Erlich, a professor in McGill’s Political Science department, wondered out loud. It was not a rhetorical question, and he waited to give his own estimate until I’d hazarded a response. “‘A lot’ is probably a good answer.”

Erlich’s POLI 311 lecture hall is one of few on campus that are peculiarly silent—not from a lack of discussion, but void of a sound so familiar that most of us probably no longer give it a second thought: The murmur of keyboards clicking as students type their lecture notes. In these courses, professors have decided to ban the use of devices in their classrooms altogether, in favour of a “tech-free” environment.

What has driven professors to implement such policies?

First on their list was the ever-present possibility of distraction offered by our devices.

“We live in an age where attention is a premium and distraction is easy,” Erlich reflected. “Your attention is monetized and everyone wants to get [it], so it’s very easy to lose.”

And with limited time per class, the professors interviewed by The Tribune expressed that every minute matters, as do the perceived pedagogical benefits of hand-writing notes.

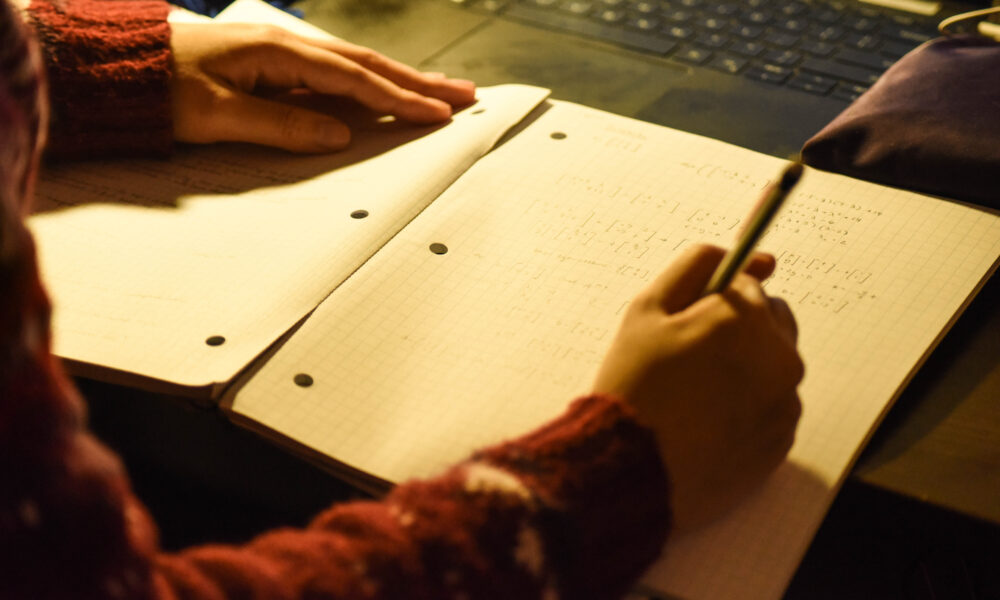

Samuele Collu, an anthropology professor, argues that transcribing lectures word for word—a habit encouraged by typing—is an impediment to learning, which requires filtering and reorganizing information.

“If I gave them a laptop, they’d be writing down every word I say,” Collu laughed, adding, “[It’s] kind of like this delusional idea that if you write down everything that has been said, you will understand more [….] But to learn is to transform, it is to synthesize.”

For Collu, having a tech-free class also gives students an opportunity to briefly step away from technology—sometimes the only moments in their lives where they are completely disconnected from their screens and notifications.

“Because we’re always so wired into technology […] even to have one hour of your time or one hour and a half of your time without [it] already creates a massive difference,” he argued. “It just changes your way of being present in the classroom.”

Cristiana Furlan, a professor in McGill’s Italian Studies department, has held tech-free classes since 2017. She noted the heightened connection and quality of teaching she feels she can offer to students who comply with her policy.

“Maybe I’m putting it in too strong a way, but it’s like a barrier somehow,” she said, referring to students who, despite her rule, continue bringing their laptops to class. “I feel like they are interacting more with the screen than with me.”

Particularly in language classes, Furlan noted the importance of forging a space where students can be vulnerable, fully present, and learning from one another—an environment which, she argued, is improved by leaving technology at the door.

“Computers do not facilitate talking to each other, asking questions to each other […] interacting with each other,” she explained.

All of these professors also aim to make their tech-free policies work for all students. Exceptions to the no-devices rule are included in Erlich’s syllabus, and students who require this accommodation, he noted, have been treated with respect by their peers. Collu’s strategy has been to carefully select various note-takers in each course, who upload their detailed notes to MyCourses after every class. He also offers lecture recordings and individualized office hours to students who require extra help.

Collu, Furlan, and Erlich all noted that, while initial resistance to their policies could be intense, by the end of the term most students got used to the change.

“[They’ll tell me they] can’t believe how good it has been to be without technology,” Collu said. “It’s a threshold that needs to be passed.”