In Canada, over 30,000 children with disabilities are being cared for at home. Caregiving for children with disabilities requires providing support in various activities of daily life, such as bathing, dressing, managing finances, shopping, and providing transportation.

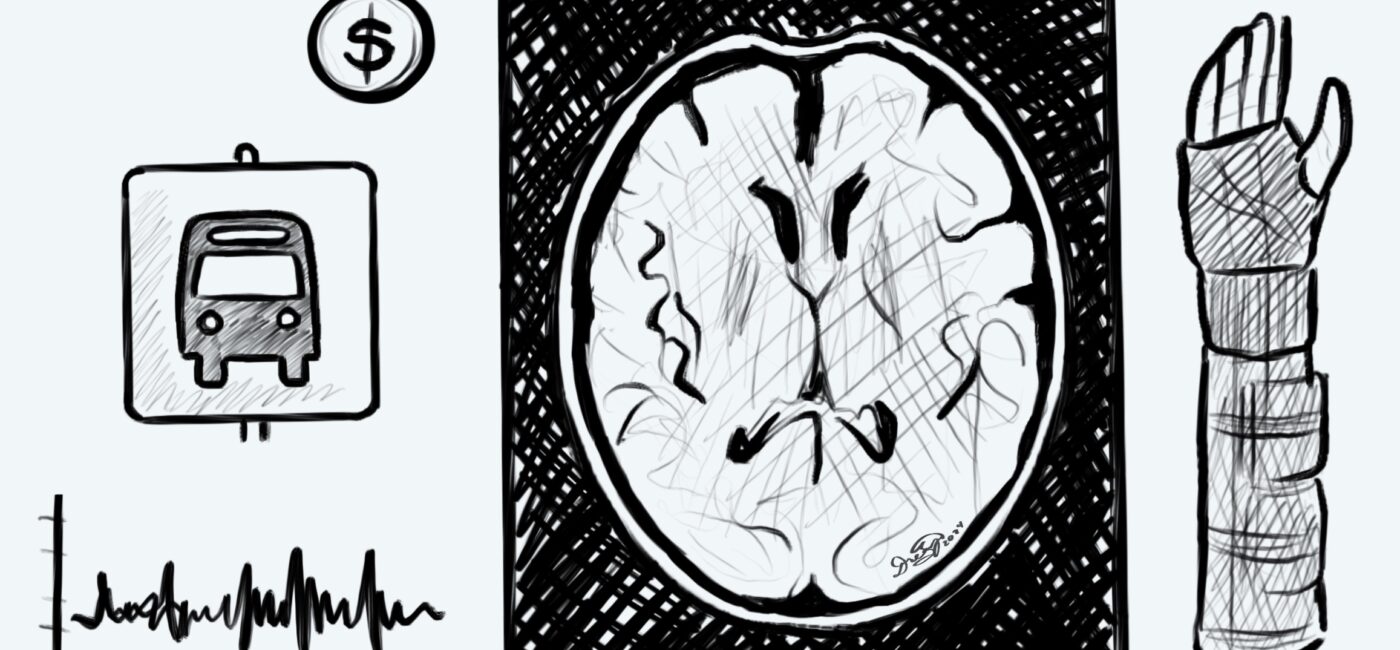

While care can be rewarding, caregivers are at higher risk of experiencing negative health effects, including mental health issues such as depression. Rare diseases such as arthrogryposis—a condition in which multiple joints are unable to fully or partially extend or bend—pose additional challenges for caregivers due to the complexity of the disease.

“Arthrogryposis is a congenital condition that affects joints from birth. It is different from conditions like joint stiffness and muscle weakness, which can develop over time,” Rose Elekanachi, PhD candidate in McGill’s School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, said in an interview with The Tribune.

Arthrogryposis commonly affects the wrists, hands, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles. In severe cases, this condition may also affect the jaw and spine. Causes of arthrogryposis are variable and may include genetic, parental, and environmental factors, as well as fetal anomalies—unusual conditions in a baby’s development during pregnancy.

The experience of providing care for arthrogryposis remains largely understudied. In a recent paper, Elekanachi and her team explored the lived experience of caregivers of children with arthrogryposis, emphasizing the financial and societal challenges caregivers encounter.

“The term ‘caregivers’ is used to refer to both paid caregivers and parents,” Elekanachi noted.

Through her research, Elekanachi aims to raise awareness of arthrogryposis among healthcare professionals and caregivers, and guide local policymakers in improving service provisions to meet the unique needs of caregivers of children with this condition.

The initial financial burden for families is considerable due to the need for numerous diagnostic tests and consultations.

“Immediately after childbirth, caregivers have to go to several healthcare professionals to receive a reliable diagnosis because this condition was very rare and [little known] a couple of years ago, and these expenses come at a significant out-of-pocket cost,” Elekanachi said.

Furthermore, the cost of caring for children with arthrogryposis varies depending on the child’s specific needs.

“For example, the child may need a walking aid, arm splints, ramps for stairs, or adjustments for beds, and things like that. Depending on the location of the affected joint, the level of financial commitment is different,” Elekanachi explained.

According to Elekanachi, the caregiving experience is complex, as this condition often requires multiple types of care, including rehabilitation, speech therapy, and orthopedics—surgeries treating conditions of the bones, joints, muscles, ligaments, tendons, and nerve structures.

Elekanachi also discusses the societal challenges surrounding the condition, including accessibility issues in public spaces, and highlights the need to allow people with arthrogryposis to speak up for their unique needs and advocate for themselves.

“We still have a society that may not be completely accessible to children with disabilities, such as classrooms, metro stations, and bus stops. Sometimes, the school may not have adequate equipment or accommodations for these students,” Elekanachi said.

In addition, the study highlighted a correlation between the caregiver’s health and that of the child. The multiple challenges caregivers face can increase their risk of poor health, reducing their ability to care for their child, which has been associated with increased hospitalizations.

“Going forward, future studies need to shift focus from the condition itself to [include] the secondary piece that affects the condition, such as caregiver experiences,” Elekanachi stated. “Healthcare professionals and researchers need to understand caregiving experiences across conditions and share comprehensive resources with caregivers.”