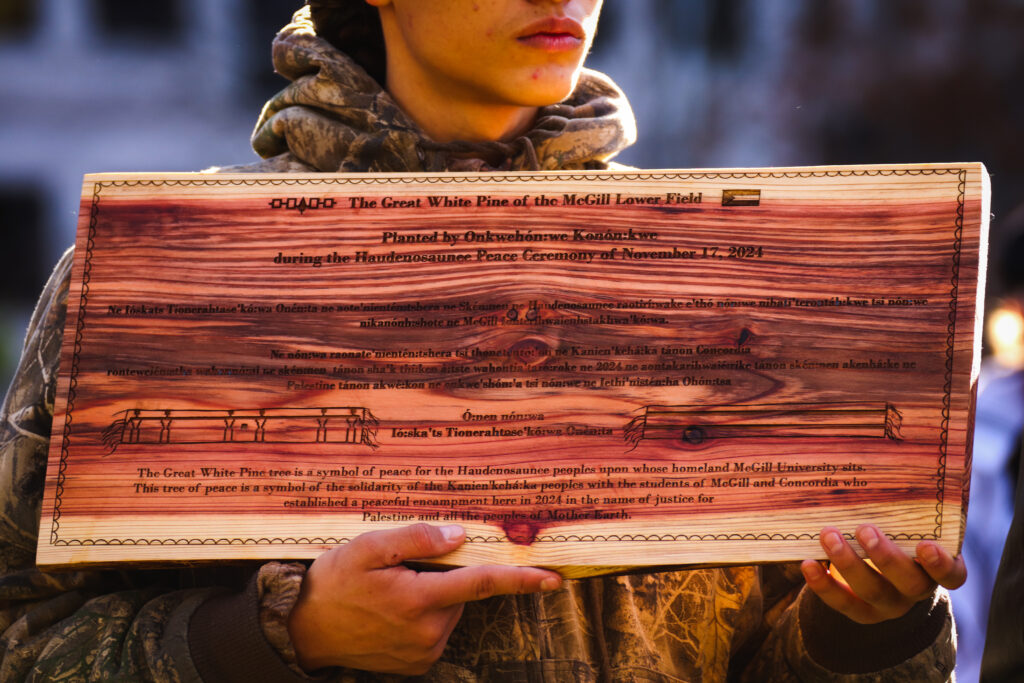

On Nov. 17, approximately 200 individuals gathered for a Haudenosaunee peace ceremony in which Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) women planted a white pine tree. The organizers then decorated it with white and purple rocks and a wooden placard commemorating the site where the Palestine Solidarity Encampment stood on the Lower Field for 75 days over the summer. The Kanien’kehá:ka women led the ceremony alongside the Palestine Youth Movement (PYM) Montreal. Within a day of the planting, McGill removed the pine sapling, an action which lead some to question McGill’s commitment to reconciliation.

At the ceremony, organizers described the event as a gesture of unity in shared struggles for land and justice, and a continuation of the solidarity expressed during the student encampment earlier this year.

“Just like the olive trees of Palestine, the white pine is a symbol of resistance and undying hope for liberation,” a PYM Montreal representative who wished to remain unnamed, explained to the crowd. “This tree of peace is a symbol of the solidarity of the Kanien’kehá:ka people, with the students of McGill and Concordia who established a peaceful encampment here in 2024.”

A Wendat graduate student from Université Laval, Marjorie Laclotte-Shehyn, came from Quebec City to attend the ceremony. In an interview with The Tribune, she emphasized the significance of the Kanien’kehá:ka asserting their right to the land through the event.

“I think it’s kind of [historic] to have an Indigenous community come here and assert that this is their unceded land,” Laclotte-Shehyn said. “They want to bring peace to this land. I hope the administration understands that they’re on stolen lands.”

The event also featured statements from Kanien’kehá:ka representatives who discussed the historical importance of the land, mentioning cornfields and longhouses that once stood there.

“This is the earth of our ancestors. This is the earth where many moccasins, many bare feet, many ceremonies, many songs were sung [….] This is Haudenosaunee land. It always has been,” Ellen Gabriel, a Mohawk activist, said.

According to a Nov. 5 written statement from the McGill Media Relations Office (MRO) to the ceremony’s organizers, the university told organizers that they would not support the proposed tree planting. Within one day of the ceremony, the university removed the tree and accompanying decorative rocks. The MRO confirmed to The Tribune that the tree had been repotted and arrangements were made to return it to the organizers.

“The organizers decided to proceed without permission. Accordingly, McGill took the appropriate action of moving the sapling and decorative rocks that were left on its property,” the MRO wrote.

One attendee, Haifa Ghassan, said that the administration’s opposition did not align with their commitment to reconciliation and demonstrates a disregard for Indigenous voices that challenge them.

“[The administration] try to say that they’re here to honour Indigenous peoples and they support reconciliation […] but they still oppress people who try to criticize their actions against Indigenous people. So I think it’s hypocritical,” Ghassan said.

Gabriel expressed her hope that McGill will accept the tree and highlighted the sense of responsibility that she and other Mohawk people feel to stand against violence that takes place on their land.

“We are making a small change to the landscape that is known as McGill. It’s a very small thing to ask. It’s a very small thing to want peace. It’s a big thing when we all participate in that peace,” she said. “We are here as well because on our homeland, we saw students being beaten up, pepper sprayed, and silenced. That’s not going to happen on our watch. We are obliged to ensure that there is peace.”

Gabriel also noted that for the organizers the ceremony was a proactive step toward justice, bypassing institutional barriers to take matters into their own hands.

“We’re not waiting for McGill to begin reconciliation. We’re starting reconciliation right here, right now, under our terms and our laws and in our way and in our protocols.”

In response to McGill’s removal of the tree, Onkwehón:we Konón:kwe (Women of the Land) sent a letter stating that they had nothing to gain from the ceremony other than spreading the message of peace, and decried the uprooting as violent.

“This desecration to the Haudenosaunee symbol of peace is also a hate crime […] This is not reconciliation, it’s a praxis of colonialism,” they wrote. “History will judge them.”