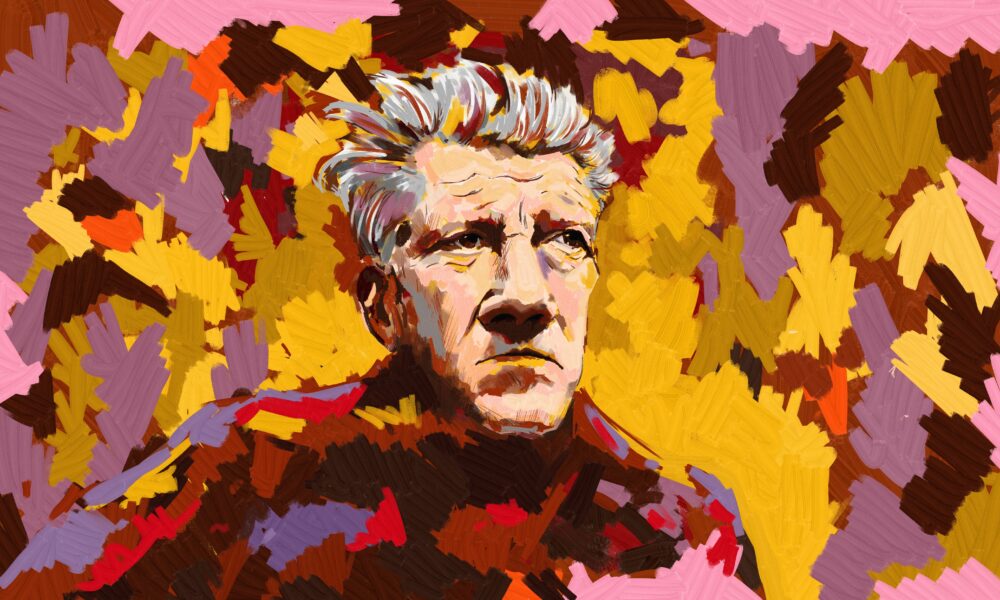

How does one memorialize a life? Through the images they have created or traces they have left behind? How can one encapsulate an entire legacy from the ashes of bodily presence? Treading in the wake of David Lynch’s recent passing, our world can reconstruct these traces from his transcendental cultural voice, his poignant and subversive narratives, and his eternal mark on the world of contemporary cinema.

Having been trained as a painter in university, Lynch’s cinematic career began with his 1967 short film Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times), stemming from his desire to witness his creations in motion. It’s a jarring and elusive piece that set in stone decades of poetic nonconformance to the cinematic form. With his painterly past, Lynch frames each shot as if an oiled canvas, shaded by the intense threat of the looming, chiaroscuro-ed darkness.

In Lost Highway, shadows become a palpable character within each scene, caressing disillusioned expressions of the characters’ gazes and the arching corridors of each shot’s background. Rich in pigment and cinematically expansive, his worlds inhabit the ruinous crevices of our own environment, twisting the figments of our reality into landscapes of surreal inhumanity, and thus manufacturing his films as depraved mirrors of America’s abhorrent corruption and nightmarish truth.

There is an elegiac quality to the disturbing nature of Lynch’s cinematic imagery and narratives. 1977’s Eraserhead’s visually gut-wrenching depiction of the aching fears of unexpected fatherhood illustrates a kindness within monstrosity and a bleakness in conventional humanness. Though visually barbaric in its finale, is a father’s greatest fear not the total unravelling and subsequent death of a child? By submitting his narrative to complete abstraction, Lynch encapsulates the violent, burdening emotionality of bearing parental responsibility. He treats his characters with such grace, allowing the full spectrum of their emotions to be rendered on screen: The gross, the extravagant, the sexual, the intense, the immoral—they all intersect in his larger vision of the world. There is an emotional purity that filters through a “caught” idea, no matter how nauseating or cruel.

In an early interview, Lynch stated, “Ideas are so beautiful and they’re so abstract. And they do exist someplace—I don’t know that there’s a name for it. I think they exist, like fish. And I believe that if you sit quietly, like you’re fishing, you will catch ideas. The real, beautiful big ones swim deep down there so you have to be really quiet and wait for them to come along.”

His worlds are mind-bending and emotionally disconcerting, as if existing within mere miles of another desolate landscape in the Lynchian cinematic universe. The elusive town of Twin Peaks, Washington—from the eponymous franchise—is perhaps Lynch’s most fully realized surrealist environment. Hidden within the seeming tranquillity of the suburban town lies traumatic abstractions of murder, arson, and incest. Twin Peaks cinematically embodies the architectural ideals of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or the “total work of art,” moving a viewer into total immersion with its creeping synthesizers, plaid-skirted characters, and assaulting pigmented visual qualities.

David Lynch would likely wish for me to finish this piece with a disturbingly close distortion of Laura Dern’s digitally altered, leering grin, but it feels right to end how much of his films do: With a deep realization of the institutionalized falsities of human nature—the idea that the power of unflinching, pure, depraved creativity overcomes the insistent challenges of our utopian-contemporary world. His visionary mind scars my life with such intense meaning, like so many others who have had the privilege of witnessing his films. His accomplishments aren’t only apparent in the recent adjectivization of his last name, but from his endless creative influence on the vastness of visual culture. There will never be anyone as authentically weird, linguistically Midwestern, and boisterously himself as David Lynch.