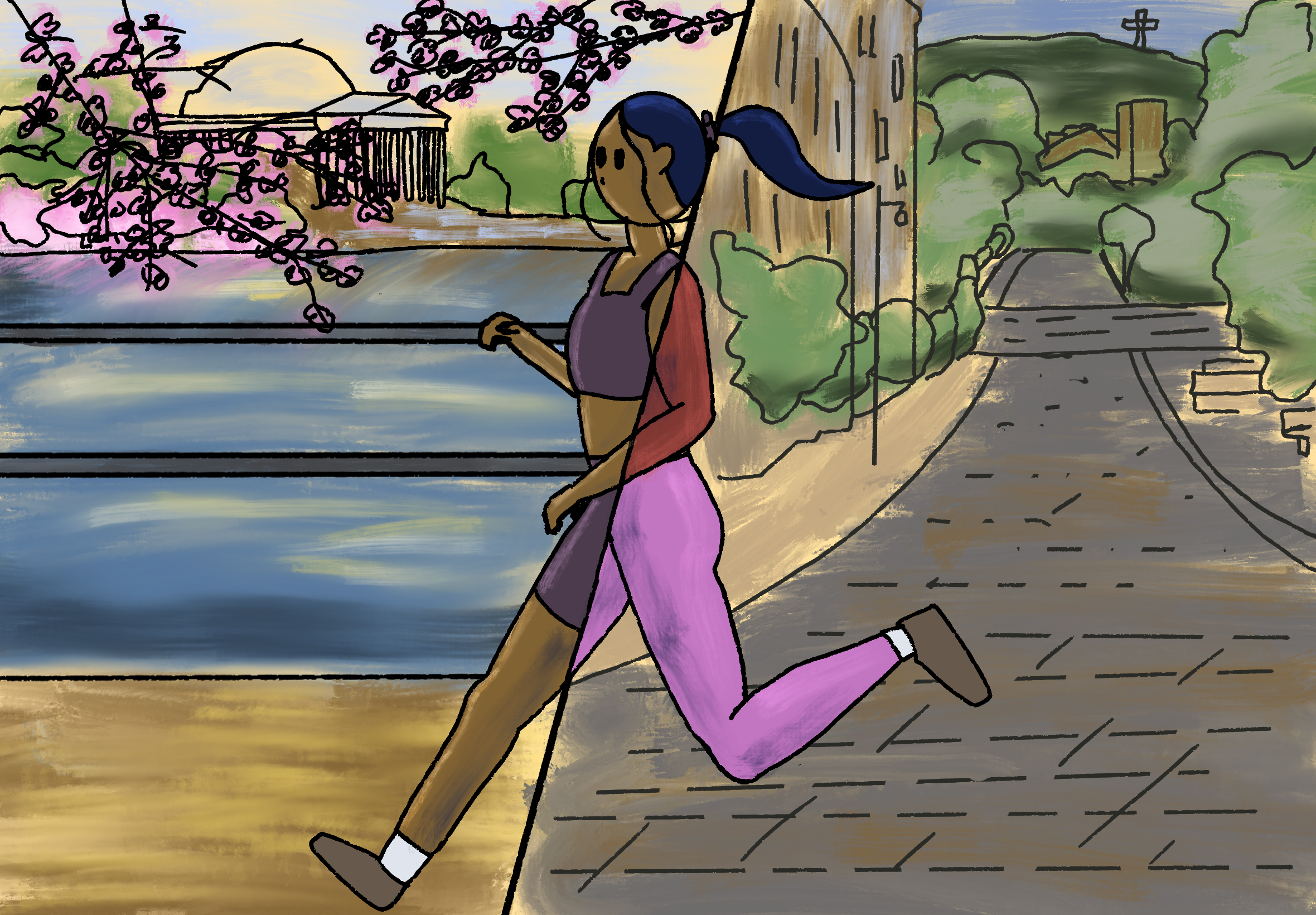

Curating a culture of active living is central to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainability and Development Goals (SDGs), specifically SDG 3, healthy living, and SDG 13, climate action. Active living is a lifestyle that promotes physical activity as an integral part of daily life—whether it be cycling to work or choosing to walk instead of drive—which has been shown to improve health and boost creativity.

However, creating societies built around active living goes beyond convincing everyone to take up a recreational sport. The infrastructure itself significantly influences the exercise choices people make.

This relationship was recently explored by Grant McKenzie, associate professor in McGill’s Department of Geography, whose paper in the Journal of Transport Geography analyzed the effects of infrastructure on running habits, in particular focusing on the gender divide in recreational running.

“We looked at some spatial and temporal patterns, and we also looked at some regressions to basically tell us what factors in the built environment, as well as socioeconomic and demographic, contribute to where men and women would choose to run,” McKenzie said in an interview with The Tribune.

Using data from Strava, an exercise-tracking app, McKenzie analyzed the habits of recreational runners in Washington D.C. and Montreal. His research supported previous findings—there is a clear gender divide in where and when people choose to run—but also provided new insight into the role infrastructure plays in these decisions.

While it was not surprising that women are more likely to run during the day than at night, the difference was more profound than expected, with only 8.8 per cent of running activities conducted by women in Montreal during the night—compared to 13.1 per cent of running activities by men.

“We looked into a couple cases in Montreal to find certain areas where there was a dominance of women running during the day, and then that completely disappeared, and [that same area] was more dominated by men in the evening and night,” McKenzie said.

While the presence of women runners decreased in some areas after nightfall, other areas saw an increase in women runners at night compared to during the day. Infrastructure played a key role in these patterns.

The study found that at night, women preferred routes near bike lanes, parks, and public landmarks, illustrating how city design influences perceptions of safety.

“There’s a lot of evidence and research on things like street lights: Having street lights and having homes with their outdoor lights on has a big impact on where people choose to walk and the perception of safety in a neighbourhood,” McKenzie explained.

Interestingly, while McKenzie’s team initially hypothesized that crime levels would dictate where women ran, they found only a weak correlation. Instead, the perception of safety was a stronger determining factor.

“There’s some background from the social psychology literature on this: That crime actually isn’t a representation for perception of safety, and so perception of safety and crime are actually very different beasts,” McKenzie said.

These findings highlight the complex factors necessary to address to make active living accessible to all.

“A lot of [our findings] have big implications for how we organize our public space. We’re helping to answer what it means for public policy to encourage development, safe spaces, and the development of neighbourhoods for active living, and a lot of this work is aiming to help that discussion,” McKenzie explained.

Ultimately, this work amplifies the voices of those who rely on active transportation. In North America, cities are largely built around private vehicles, often overlooking the needs of pedestrians and cyclists. Addressing these gaps is key to the creation of truly accessible and vibrant urban spaces.