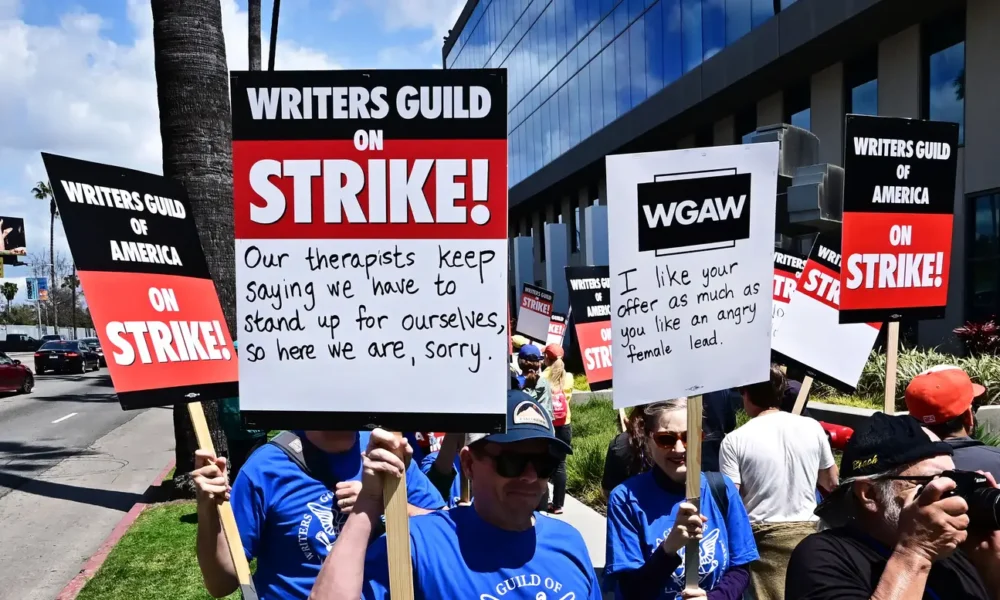

On May 2, the Writer’s Guild of America (WGA) went on strike against the American Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) to protest for fair wages, promises against the use of AI, guarantees about job duration, and other issues—shutting down the majority of continuing projects and stopping new shoots from starting. According to The New York Times, the strike interrupted approximately $10 billion worth of projects.

Under the original royalties plan, the writers would get paid every time a show or movie that they were credited on was run on cable television or bought on DVD or Blu-Ray–a sensible plan when those mediums were still widely used. Consumers now rely on streaming services to the extent that other forms of motion-picture consumption have become practically obsolete, so this agreement needed restructuring to give writers fair residuals from streaming viewership.

WGA structured their demand for a minimum number of writers per project with the aim of shutting down “minirooms” in Hollywood—writers’ rooms with only a few writers that quickly produce scripts in a period of about two to three months. The issue with these minirooms is their instability. Only a few writers are hired per show, and if the show doesn’t get picked up, the individuals have to scramble to find new jobs. Additionally, minirooms reduced the number of writing positions available, making it harder for new writers with fewer connections to break into the industry.

The union also wanted to guarantee protections against the growing threat of AI encroaching on writers’ jobs. The WGA was unwilling to compromise on this point; they wanted guarantees that AI would not take away writers’ jobs or be used to write original material.

On Sept. 25, day 146 of the strike, the WGA and the AMPTP reached a new deal regarding the writers’ contracts. The terms of the strike, which are now public, show that the writers were successful in obtaining many of their requested guarantees. These include a promise against the use of AI, a better residual payment plan for shows on streaming networks (an increase of 3.5 per cent to 5 per cent), and promises about minimum staffing and minimum job duration. The WGA’s leadership board has approved this deal, so it is now up to the writers to ratify the agreement by early October. However, the writers are allowed to start working again prior to the agreement’s official ratification.

The deal has been widely lauded as a success. This contract sets a vital precedent for what is to follow with screenwriters and the entertainment industry as a whole. The streaming model is not going anywhere anytime soon, which is why it was crucial for writers to secure better residuals now rather than later. The writers, having received nearly everything they asked for, are happy with the agreements in their new contract. There were compromises on certain salary and percentage increases, such as the percentage of increased weekly rates for TV writers, as well as on the worth of their deal; after the AMPTP countered their original ask of $429 million with an offer of $86 million, the two organizations settled on a deal worth $233 million. Their contract will be renegotiated every three years and will most likely improve with each iteration.

However, the end of the WGA strike does not necessarily mean that scripted television and movie projects will be returning quickly. The Screen Actors’ Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Actors (SAG-AFTRA) remains on strike over their contracts with the AMPTP for many of the same reasons as the writers. While the WGA strike is over for now, there are still measures that harm entertainment unions’ workers, such as California Governor Gavin Newsom’s veto of a bill requiring unemployment benefits for striking personnel. Amidst hope and anticipation of a SAG-AFTRA deal, it is vital that contracts are continuously amended to ensure fair rights and wages for all.