I walked through the doors of the Montreal, arts interculturels (MAI) last Friday to find the exhibit space deserted. “Excellent,” I thought to myself, as I passed the archway to the main hall—the stormy afternoon seemed an opportune time, and the ideal backdrop, to see the MAI’s latest offering, Blown Up: Gaming and War.

The exhibit’s arrangement exudes an ominous atmosphere, like some ephemeral worry one can’t quite remember. It is difficult not to appreciate the effects of this backdrop: viewers’ footsteps echo when striking the wooden floors, and the dim light pushes one’s gaze to the three pieces.

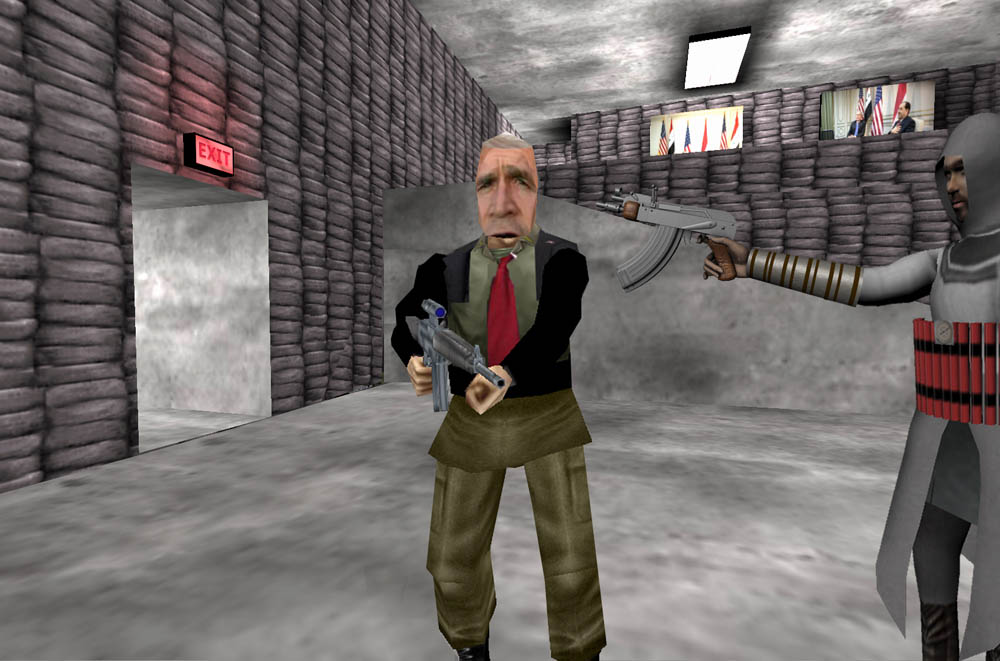

The first sight to greet visitors entering the sparsely arranged space is a lone, illuminated podium, atop which rest a keyboard, headphones, and mouse. On the opposing wall, a projector displays the title screen of the game, Wafaa Bilal’s The Night of Bush Capturing: A Virtual Jihadi (NBC:VJ). The idea alone is intriguing: Bilal inserted a graphical representation of himself, virtually recruited to assassinate George Bush Jr., into a two-bit piece of al-Qaeda propaganda entitled The Night of Bush Capturing (2006). The game consisted of the player passing six levels to eventually assassinate the former president. This, in turn, was a crudely orchestrated instance of cosmetic surgery on another game, an equally obscene piece of programming by the title of Quest for Saddam (2003), wherein players mow down Saddam-lookalikes until—surprise—they kill the final Saddam (in a humorous twist, the al-Qaeda version attempted to remove anything remotely American from the game, such as the Red Cross packs players can use to boost health; nevertheless, al-Qaeda’s programmers seemed to have forgotten an open book on the first level, which displays a picture of a camel).

I spent the better part of an hour on Bilal’s provocative piece (when the exhibit initially opened in the U.S., it was boycotted and shut down by locals who, never having had a chance to play the game, were uncertain as to why exactly it was that they opposed it), failing to see how it differed from the al-Qaeda iteration. Terrible gameplay, painful graphics, and offended gaming sensibilities aside, NBC:VJ provided disappointingly little by way of political statement: the credits still listed the “Global Islamic Media Front” (GIMF—a suitably inane acronym) as responsible, and Bilal’s avatar was nowhere to be seen.

Only having come home, and scouring the web for details on the game, did I discover the hitch: Bilal chose to make minimal adjustments to the game. In fact, when demonstrating NBC:VJ at a Rensselaer Institute lecture, Bilal noted “Just don’t blink because you’re going to see me in the game, and if you blink you’re going to miss it.” Rather than communicating the pervading sense of danger and alarm gripping Iraqi citizens, as was his aim, Bilal essentially shanghais the player into participating in a piece of al-Qaeda propaganda.

Due to space constraints, I can say little about the remaining pieces. Harun Farocki’s Watson is Down, one quarter of his Serious Games I-IV video installation, repeatedly plays on another wall; it’s akin to listening to a quarter of a song, and the lack of context that the three remaining pieces would have provided is strident.

The final piece, Mohammed Mohsen’s Weak, was, perhaps, the most interesting. Housed in a sleek black arcade-game exterior, Mohsen’s work rests between those of Farocki and Bilal, its default Windows 98 flying-star screensaver and foreboding joystick inviting players to try their luck. When I gripped the joystick, the screen filled with half-formed, pixelated shapes. Gunfire and sounds of military communications emerge, failure messages appear, but there is neither a goal, nor any sense of control. A blooming buzzing confusion ensues, coupled with a prevailing sense of discomfort. Such sentiments are well within the scope of the work: Mohsen attempts to portray tragedy, reconstructed from half-formed memories. Still, the same results may be derived from the press release, which states that “absurdity acquires meaning in the intimacy of nostalgia, amidst violence and tragedy.”

In spite of the atmospheric setting and flashes of emotion, Blown Up remains a regretful testament to the difficulties of communicating through novel media rather than a poignant portrayal of conflict. In the meantime, to those wishing to experience gaming and war, I recommend reading Owen’s Dulce Et Decorum Est and picking up a copy of Call of Duty.

Blown Up: Gaming and War runs until Dec. 15 at the MAI (3680 Jeanne-Mance, bureau 103), Free admission.