It’s rare for a band like The Rolling Stones to be embarrassed or even scandalized by anything, but the footage in Robert Frank’s documentary Cocksucker Blues was evidently too much for the band to reveal to their public. Despite the liberal atmosphere of the early ‘70s, which saw the explosion of classic rock—and the hedonism that came with it—Cocksucker Blues was deemed inappropriate for public audiences. The issue was taken to court, and it was finally decided in 1977 that the film could not legally be shown until 1979, and then only four times per year, and only with director Robert Frank present at each showing.

Cocksucker Blues was exhibited in Montreal’s Festival du Nouveau Cinéma on October 16, the first official screening of the film since the Museum of Modern Art screened it at The Rolling Stones: 50 Years of Film exhibition in 2012. Montreal was one of the places Frank first illegally showed the film.

It’s safe to assume that the majority of those attending the screening arrived with a basic background on the Rolling Stones as a seminal cultural phenomenon and a wild caricature of the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle. Whether most of the audience was there to bask in the heyday of classic rock hedonism, or scoff at the very same thing, it required real grit to sit through the raw, often-humourless footage of their 1972 Exile on Main St tour.

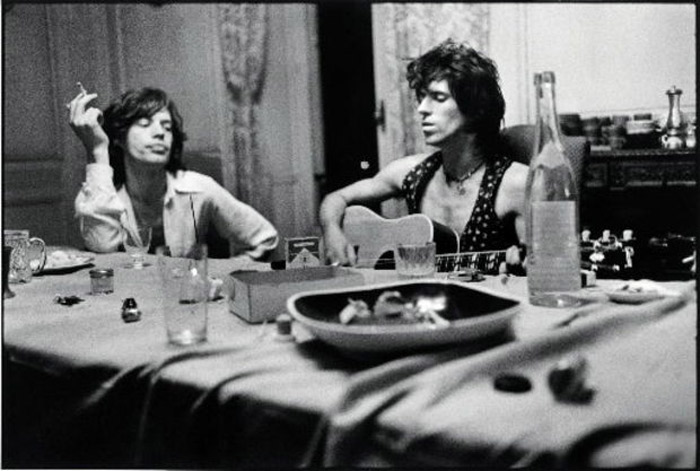

The film was shot in a cinéma vérité style, which contributed to its disjointed nature. Cinéma vérité is a rather broad genre of documentary film, conducted in this case by providing several cameras for band members, groupies, and sound engineers alike to record what they saw on tour. The result—compiled in the editing room by Frank to lend some semblance of story—is a shaky, often random, and even cringe-inducing record of The Rolling Stones’ lifestyle. The film failed to reveal the glamour of life on the road with the Stones and the excitement of cultural revolution that comes with many rock documentaries (see The Last Waltz or Monterey Pop). Instead, the film’s unflinching lens casts a pall over the orgies, injections, lines, and parties. While some interviewees are gregarious and giddy from drug use, their words have little more consequence than the stoned musings of the average person.

There are moments of joy that break through the dizzying close-ups of naked girls and heroin users. The longer concert scenes showcase the band at their best: In a haze of glitter, velvet, smoke machines, and screaming riffs to go along with Keith Richards’ mad guitar solos. Other innocent scenes remind the audience of the Stones’ humanity, such as when Mick Jagger goes through a painstaking process to order a bowl of strawberries and blueberries to his room in a middle-of-nowhere hotel.

Ultimately, Cocksucker Blues succeeds in that it is not a glamourization of debauchery but an honest look at it. The film exhibits an unedited view of the Stones in all their hedonist glory, and that includes many moments of vulnerability and some of dazzling invincibility.