Spoilers for American Fiction

“Nuance doesn’t put asses in theater seats.”

At least, that’s what fictional movie director Wiley Valdespino (Adam Brody) says in the final scene of Cord Jefferson’s American Fiction. In the Cineplex that I trekked out to on a Tuesday after class, the audience let out a collective laugh. I looked around suspiciously. Then why are there so many asses in these seats?

There is no denying that American Fiction is a nuanced movie filled with meta-cinematic moments and witty dialogue. But when protagonist Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright) adapts his life into a screenplay, Wiley points out that a story with an ambiguous ending won’t work for a movie. As they cycle through potential endings for the film—letting them play out on screen—the film self-consciously sheds light on the difficulties of adaptation.

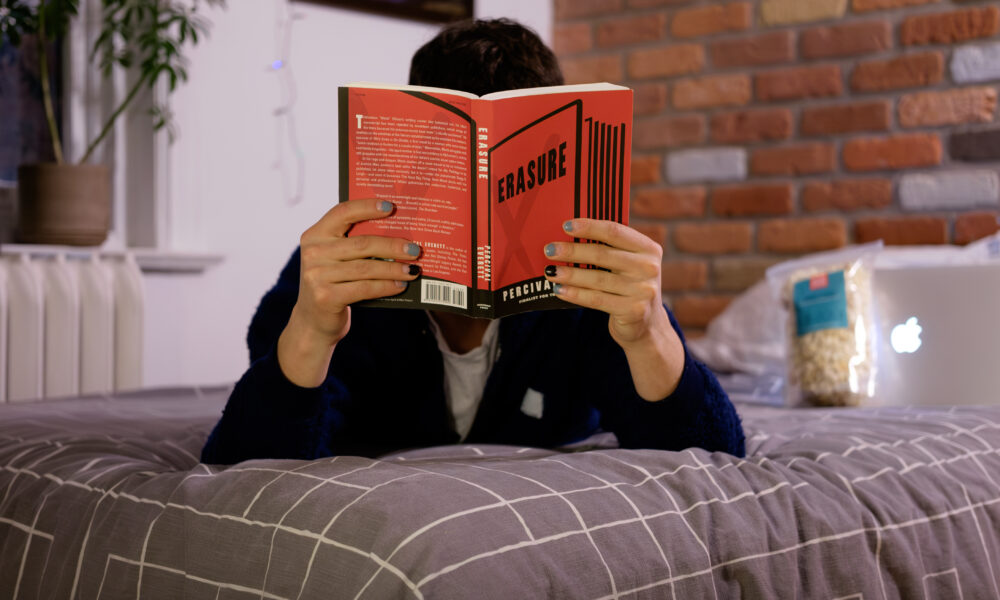

American Fiction is, itself, a literary adaptation of Percival Everett’s 2001 novel Erasure. When I first read Erasure, I hadn’t met anyone outside of my English class who had even heard of it, but somehow I found myself attending a packed screening of American Fiction almost a month after the film’s theatrical premiere. How has the process of adaptation given this story new meaning?

Erasure is a book about books. It follows Monk, a professor and writer who is repeatedly told his work isn’t “Black enough.” In response, Monk writes a satirical, intentionally offensive novel called “My Pafology,” giving his publishers what they seem to want. He publishes it under a pseudonym, only to find that the novel becomes an unironic bestseller. Erasure identifies the limited literary space that publishers give to Black authors, where depictions of poverty and dysfunction are lauded over the multiplicity of Black experiences.

Erasure is sprawling and multifaceted, with digressions that encourage close reading. By contrast, American Fiction strips away the more ambiguous details, instead emphasizing the plot-driven family drama and comedic moments. The novel chooses to print Monk’s book in its entirety, filling 60 pages with over-exaggerated dialect, blatantly offensive stereotypes, and violence. This works as part of the novel’s complex patchwork-like structure, allowing readers to experience exactly the kind of exploitative book Erasure is critiquing. By contrast, inserting such a huge tonal shift into American Fiction would complicate its genre-signaling. Instead, Monk’s novel is depicted in a single short scene, where his characters materialize in front of him as he writes in his office. As Monk dictates their dialogue, American Fiction manages to convey the voice of the novel without engrossing viewers in gratuitous violence or compromising the film’s comedic tone.

The focus of Erasure’s critique is the literary field. Released in the early 2000s, it scrutinizes the critical acclaim of books such as Sapphire’s Push, a novel that excessively depicts Black trauma. While Erasure assumes that its readers are more familiar with the literary landscape, American Fiction can’t assume the same from its audience of moviegoers. Because of this, the film includes a final scene that poses a new critique. The white director of Monk’s screenplay rejects all of the film’s potential endings only to finally show enthusiasm when Monk suggests a violent conclusion involving police brutality. As he leaves the film lot, Monk shares a nod with a young actor dressed in the costume of an Antebellum-era enslaved person. Here, American Fiction shows how depictions of Black pain continue to retain cultural capital in the mainstream context. By broadening the scope of its commentary to form a meta-critique about movies, American Fiction manages to convey the essence of Erasure while expanding its reach to a wider audience.