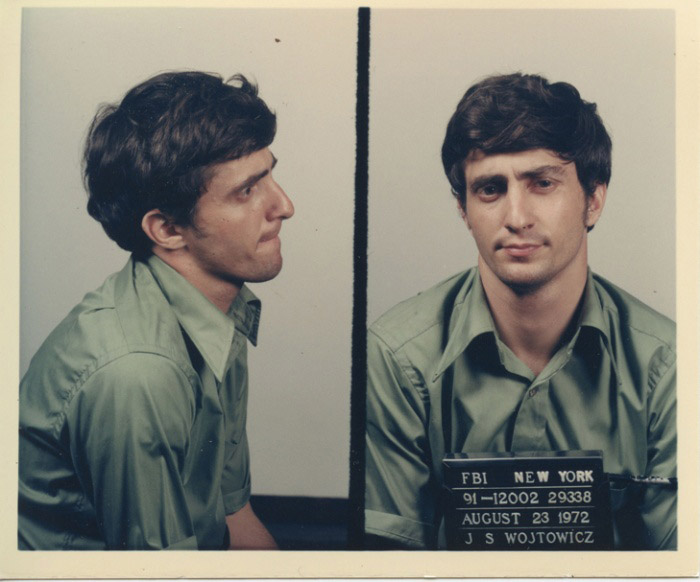

In 1972, New Yorker John Wojtowicz was captured attempting to rob a bank. Despite his arrest, he had no regrets—but why would he, now that he has two films made about him?

Wojtowicz was first memorialized in 1975, three years after his attempted robbery, when he was portrayed in Dog Day Afternoon by none other than Al Pacino himself. This film influenced and dominated Wojtowicz during his remaining four years in prison so that by the time he was released, he identified more as “The Dog” than John. Those closest to him expressed distress that he changed after the robbery, embracing the chaotic persona Hollywood made him out to be, and it is this part of the story that becomes emphasized in The Dog, a biographical piece co-directed by Frank Kerauden and Allison Berg.

The Dog—which, through interviews, covers Wojtowicz’s life from his childhood to his attempted bank robbery, and into his celebrity status following his release from jail—is bound from the start to be incredibly entertaining. Wojtowicz is a lively main character who, despite aging significantly through the course of the interviews, retains his braggadocio and delusions of grandeur—even when they’re fascinatingly countered by others.

The film features the opinions of almost every character mentioned in his story. All of his ‘wives,’ his mother, hostages of the bank robbery, inmates, his psychiatrist, and previous journalists who covered his story. Alternating between photographs, old footage, new footage, and traditional interview shots—with voice-overs of those involved—the 105-minute film moves surprisingly quickly.

Wojtowicz explicitly focuses his early life on sex, constantly seeking it with both genders, and proudly declaring himself as a “pervert” to the co-directors. Although his involvement with the Gay Activists Alliance was used as a means to meet more lovers, the film uses his time with the Alliance to explore the gay rights movement, bringing up old footage of meetings, marches, and news stories as they discuss issues still being debated today concerning gay rights. Yet the film deftly avoids presenting any strong views—only the expression of peoples’ opinions as they relate to Wojtowicz’s story specifically. Although he received a lot of attention for “tonguing” another man during the news broadcast covering the robbery—what he called “the ultimate act of gay activism”—the movement as a whole distanced itself from this man who could easily give a bad impression of gay people as unstable or dangerous.

The film is able to stay away from retreading any ground established in Dog Day Afternoon, excluding some news footage from the robbery itself. While Sidney Lumet’s flick gave Wojtowicz notoriety, The Dog exposes the aftermath of the chaos created by the press for an already eccentric man.

In the end, it’s hard to say whether or not the audience should pity the man whose life was dominated by the press or simply enjoy the ride alongside him. The film subtly presents a lingering idea of discomfort within Wojtowicz about who he really is, and that question of identity drives the emotional theme of the film. The film is a commentary on gay culture, celebrity culture and convict culture through the lens of a dozen anonymous New Yorkers who happened to get involved with John “The Dog” Wojtowicz.