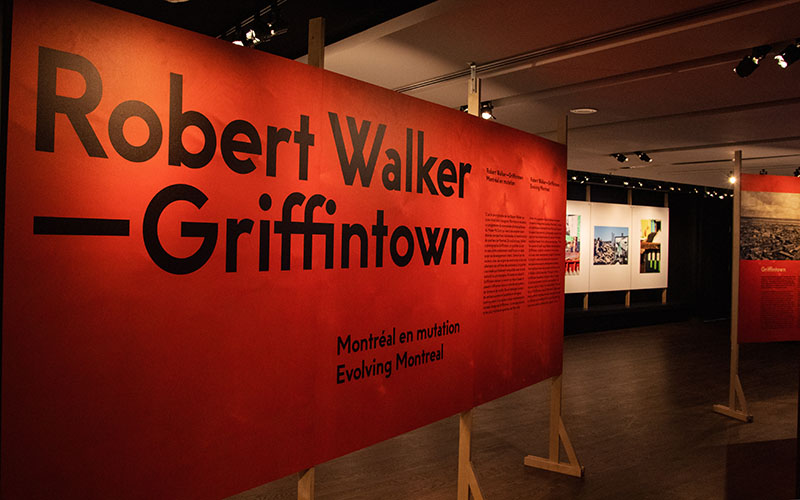

Urban redevelopment looms over Montreal with a constancy that borders on parody. Whether these changes impact a single street or an entire neighbourhood: The threat of an orange cone is ever-present. Since 2013, Griffintown—downtown’s southwestern neighbourhood, historically home to Irish industrial workers—has been Montreal’s most recent target for urban renewal. In collaboration with photographer Robert Walker, McCord Museum premiered Griffintown – Evolving Montreal on Feb. 7, a photo exhibit documenting the quarter’s identity in flux. The exhibition is one of many that McCord will curate to document Montreal’s evolution as a whole. Walker is a veteran street photographer whose subjects have included the urban landscapes of New York, Paris, and Toronto.

In a video that accompanies the exhibit, Walker notes that he does not intend to gauge gentrification’s impact on Griffintown as a historical or social artefact. Given his self-proclaimed surface knowledge of the district, he is instead invested in capturing how aggressive construction produces harsh contrasts in urban landscapes. Walker’s photos reveal a battle over Griffintown’s topographical aesthetic.

In one photo, grey apartment complexes tower in the background, conveying urban uniformity and progress. Meanwhile, a messy construction site with bright orange barriers foregrounds the image, tainting the background’s promise of aesthetic pleasure and disrupting the landscape’s organization. Imbalances of colour, shape, and materials populate all of Walker’s images as a means of surveying the area’s irreconcilable tensions. Another photo captures an excavator behind the brick wall that it’s tearing town. The image is a literal window into the demolition underway in Griffintown, but its highly saturated colours and bright blue sky clashes with its dour scene of destruction.

Time itself is under contention in Walker’s photography. In the video, Walker comments on how remnants of the past linger in Griffintown amidst rapid development. One photo depicts a horse-drawn carriage as it travels down one of the neighbourhood’s streets. In the image, a glaring and enlarged construction sign distracts from the horse as it recedes from view. As a visual representation of the saying, “out with the old and in with the new,” contemporary renewal discards nineteenth-century transportation, rendering the disappearance of the past tangible.

Similar to his obscuring of its past, Walker’s Griffintown fragments its identity by obsessing over its future. Billboards populated by minimalist condo interiors, luxury sports cars, and model-like residents appear in several of the exhibit’s photographs. Walker contrasts these picturesque visions of the future with Griffintown’s current landscape—industrial construction sites, piles of concrete, abandoned apartment tenements. Often, Walker hides these billboards’ edges so that their content appears continuous with the reality of the present. When, in Walker’s photos, residents look at the billboards’ promises of utopian modernity, their landscapes become illusions whose artifice is undone by Walker’s own images of current-day Griffintown.

“I always like to exploit the contrast between the selling techniques of the developers that insinuate the purchase of a condo with glamour,” Walker says in the video, “and the reality of the raw bricks and mortar structures.”

Under Robert Walker’s eye, Griffintown is a neighbourhood at odds with itself. Its priorities, which emphasize demolition and illusory distraction, pull it apart in opposing directions. Gritty piles of rubble and incomplete infrastructure compete with landscapes meant to advertise the neighbourhood’s desirability. The result is an anachronistic limbo, a space where Griffintown’s past refuses to cede to the accelerated development imposing itself on it.

Griffintown – Evolving Montreal runs until Aug. 9 at the McCord Museum (690 Sherbrooke St. O).

Student tickets – $12.