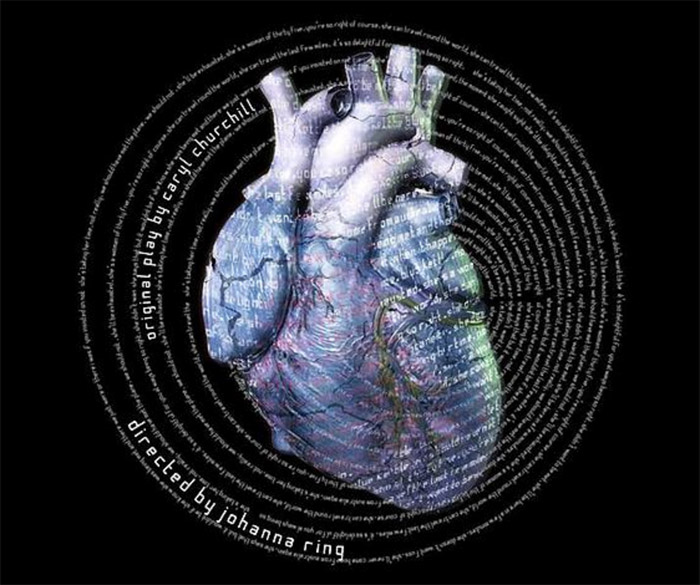

Strange and elusive energies crackle with abandon on the Tuesday Night Café (TNC) stage in Caryl Churchill’s unnerving Blue Heart, a production of two one-act plays performed as a set. Teasing apart cruel dimensions of language and longing in a theatrical experiment in form, the self-sabotaging construction of the play suggests dark avenues of fear and confusion, and watching it conjures the inconceivable giddiness of absurd hilarity.

If there is connective tissue between the two acts, it’s dark and anguished. The first act, “Heart’s Desire,” is a shifting, swirling melodrama where a family is unlatched from time and sent swinging along its own track, careening into countless futures with each buzz of an offstage buzzer. The light falls, and the scene resets,drafting versions the play might take up sometimes sped up, sometimes in halting phrases, and discards each in turn.

The first act tells the unraveling story of a married couple–Brian (Max Katz) and Alice (Amalea Ruffett)—as they wait with Brian’s sister, Maisie (Sasha Blakeley), for the return of their daughter, Susy (Natalie Liconti). Almost at once the marriage seems on the point of collapse, as the play retreads the same scene countless times, to dizzyingly different results. All of this occurs in a perpetually melodramatic arena: The kitchen. Set Designer Chip Limeburner’s spare set conjures abstractions of unrest.

Visitors arrive to disrupt the scene. An alcoholic son (Martin Seal) emerges from a drunken stupor to terrorize the family, ski-masked and gun-toting thugs arrive to assassinate everyone, and a giant bird unfolds from the doorway. The gaze of the characters intrudes as well; a sudden hush gives way to unsettling stares turned towards the audience. An unmistakable strain of absurdity endures throughout. Thus the spirit of this act is one of preoccupied horror, braced by the unmistakable need to laugh out loud.

If there is a moment that most clearly treads the thin line between hilarity and horror, it’s the sudden fantasy that Brian unleashes on his shocked sister and wife. Katz is appropriately intense in this sequence, confessing his desire to eat himself up, bit by bit, body part by body part, leaving nothing but a mouth. He then questions whether the mouth can consume itself. The language-cannibalizing second act may offer answers.

In “Blue Kettle,” the second act, a confused young man witnesses language becoming suddenly, irrevocably unhinged. As though revealing the mutative influence of an inexpressible core, the words of the title, “Blue Kettle,” begin to infiltrate speech, substituting nouns, verbs, adjectives, until a final, wrenching scene where two characters speak haltingly in the shattered syllables of the title.

The confused man is Derek (Seal), a 40-something-year-old con man playing a strange and inscrutable game—tricking women into believing he is their long-lost son. To what end? Be it money, or a substitute for his own ailing mother, it seems not even Derek is sure. Limeburner splits the stage into three smaller sets, isolating the players within pools of light. It pulls the frenetic energy of the first half into a far more contemplative place.

Director Johanna Ring creates a more static second act as well, mostly consigning itself to calmer two-person scenes. Derek is paired his presumptive mothers, or his girlfriend Enid (Liconti), allowing subtler performances to emerge. The women are drawn into Derek’s odd orbit, but it is clear that each possesses an odd core of their own. Derek’s real mother (Kelly Lopes) delivers a quivering, fractured performance, and Blakeley forms her Mrs. Oliver at the converging vectors of shame and anxiety.

Churchill is a veteran playwright of prodigious talents and roving insight, possessing an imagination that seems both at once capricious, and laser-focused. She has written an extensive catalogue of experimental productions that hint at a restless and unsatisfied mind. In Blue Heart, this restlessness catalyzes in strange devices fixed to plot and language, causing these to become unstuck and free flowing, unraveling even as they reveal their construction.

There is a sense of pervasive dread to Blue Heart, a subtle violence that lingers in the brain long after leaving the theatre. And yet, the play’s vibrancy is unmistakable; this is not a sinkhole of doom and gloom. The aura of unease is palpable in the lobby, and yet so is the fierce glow of anarchic exhilaration. Blue Heart sticks.

Blue Heart runs from Nov. 18-21 and 25-28 at 8 p.m. at TNC Theatre in Morrice Hall.Tickets are $6 for students.