The premise is intriguing enough: Jacqueline, a female combat officer who served in Afghanistan, wakes up in a dark hospital cell complaining of a phantom pain in her amputated leg. What follows, however, is more phantasmagoric—the brilliant Zach Fraser enters the stage as Jacqueline’s French-Canadian great-grandfather, who was unjustly shot for desertion in WWI.

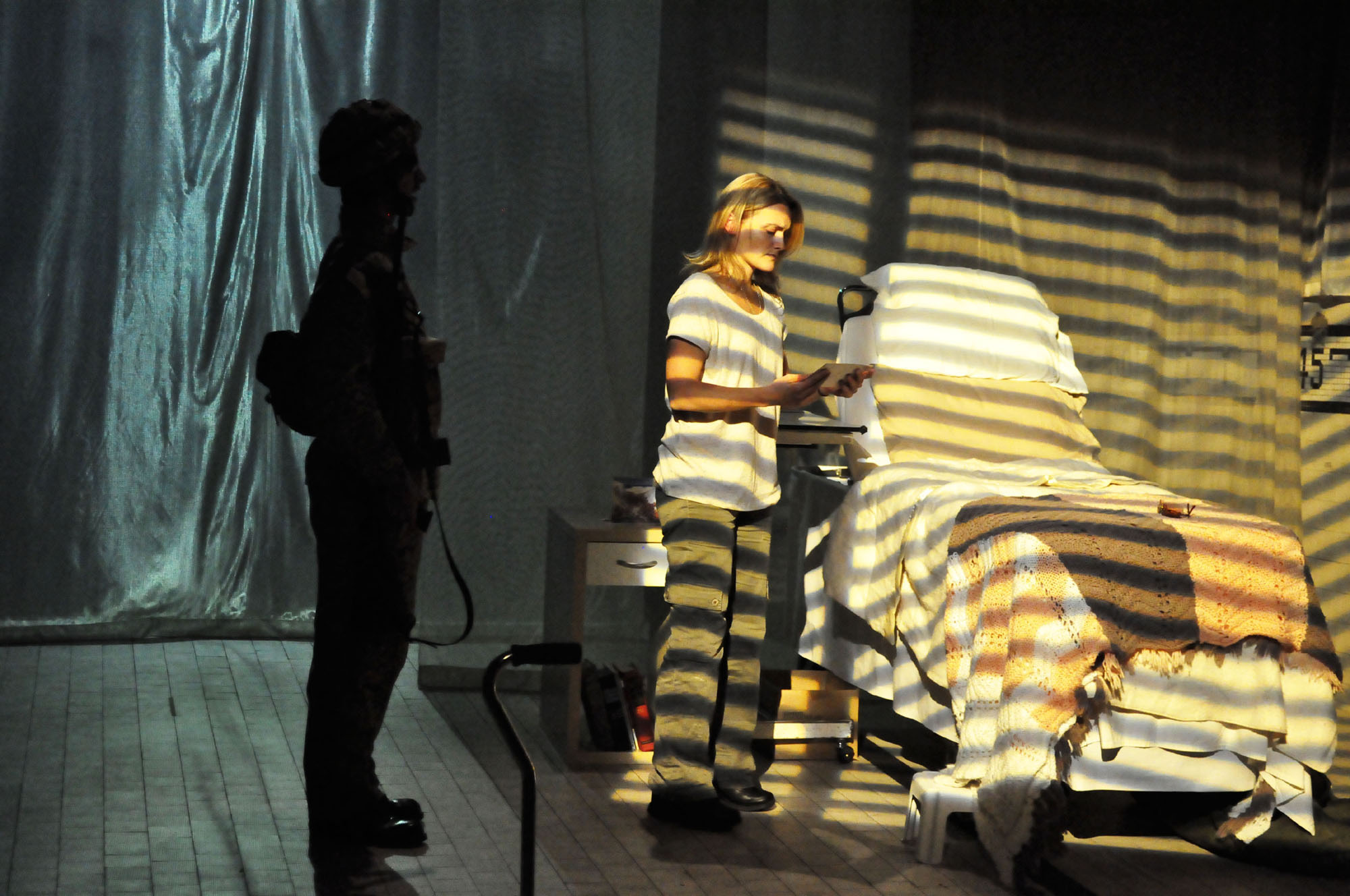

Alyson Grant’s Trench Patterns is an immersive spectacle. The lighting and sound are outstanding, and Guy Sprung’s direction in this Infinithéâtre production does full justice to the piece’s haunting experience. The play itself seldom departs from the hospital cell setting, which effectively facilitates a “brain in a vat” exploration of Jacqueline’s febrile consciousness. One by one, hallucinatory figures from both wars appear on the platform—vignettes that each pledge the case of abject humanity.

On the surface, the play questions the paradoxical concept of a “just war” and the “good soldier”—nothing new there. Yet what is new, is an ambitious creation a character distressed by a double-stranded memory, which oscillates between her great grandfather’s tragic fate in WWI, and her own participation in the Afghan conflict. It certainly baffles temporal and spatial logic to enact scenes from both wars, almost a century apart, in a hospital ward—unless this straddling of time occurs in a character suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Even so, the show requires some willful suspension of disbelief.

This is especially necessary in Jacqueline’s imaginary conversation with her great-grandfather, and her evocation of painstakingly real scenes from WWI. Of these, she has no first-hand experience—after all, she has only read about them in history books. The audience’s bewilderment mirrors Jacqueline’s disorientation in a play that, for the most part, operates at the expense of logic. Were it not for Patricia Summersett’s riveting performance as Jacqueline, the play may have failed to convince on a structural level—however surrealistic in tone Grant intends it to be.

However, it is Jacqueline’s hallucinatory plunge into history that rescues the binding theme the play desperately needs. In her introduction, Grant notes that her play is about “how a past family member’s life … can shape those in the following generations.” It is Jacqueline’s attempt to reconcile her identity as a soldier with her particular familial history that ultimately rewards a genuine comprehension of what the play alludes to.

Throughout, Jacqueline is either stuck in bed, propped up in a wheelchair, or limping across the stage; all states generate sincere pathos. The title of the play derives its name from the often twisted and zig-zagged patterns of the communication trench in WWI. Jacqueline’s road to recovery, thus, requires not only the psychiatrist (also played by Zach Fraser) and her mother (Diana Fajrajsl) to understand her, but also the audience, to make sense of her long recuperative process, physical and mental, as she interrogates both her past and present.

Grant is evidently an able playwright. Commendably, there is an almost Beckettian tinge to the wonderfully conceived character of Jacqueline. Yet Trench Patterns is very much just a demonstration of potential, raw talent on display; on the whole, it is much too ambitious, and consequently falls a little flat.

Trench Patterns runs through Nov. 18 at Bain St-Michel (5300 St-Dominque); Tuesday to Saturday at 8 p.m. and Sundays at 2 p.m. Student admission is $20.