If you had asked me at age 10 what I most wanted to be, I would’ve said a demigod. No series has ever commanded my attention and captured my affections the way that Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians saga has. His world dances along the cusp of reality and fiction, stealing my imagination with no intention to return it.

I fantasized about which godly parent might claim me, donning an orange shirt and brandishing a toy dagger. Riordan’s characters were my dearest friends and teachers, fostering bravery, cleverness, and kindness. I travelled from the entrance of the Underworld to the heights of Olympus, fought battles against Cyclopes and paddled across the River Styx without ever leaving my bedroom. I was privy to a world that no one else could see; so enamoured that during exams I painstakingly forced myself to lock away my beloved books, because how on earth could one be expected to study DNA strands when my darling characters were floundering in Tartarus?

This March, back in my childhood bedroom, I revisited my favourite passages. Staring at the worn covers, I wondered what had entranced me back then. As I flipped through the lovingly dog-eared pages (book purists, please stay calm), the sentences bore the same effect that they had on me all that time ago—a world of magic and miracles just as vivid in colour as it was through young eyes, if not more. Revisiting Camp Half-Blood as an adult, I have a deepened appreciation for its complexity.

I was drawn back by a particular passage in Riordan’s The House of Hades— an argument where Cupid forces demigod Nico di Angelo to confess his heart’s deepest secret. With more naive eyes, I had seen Cupid as a brute, a target of my impassioned anger. But reading it again led me to realize the character personifies an intrinsically real facet of love: The part that’s uncomfortable and terrifying, that strips you to vulnerability.

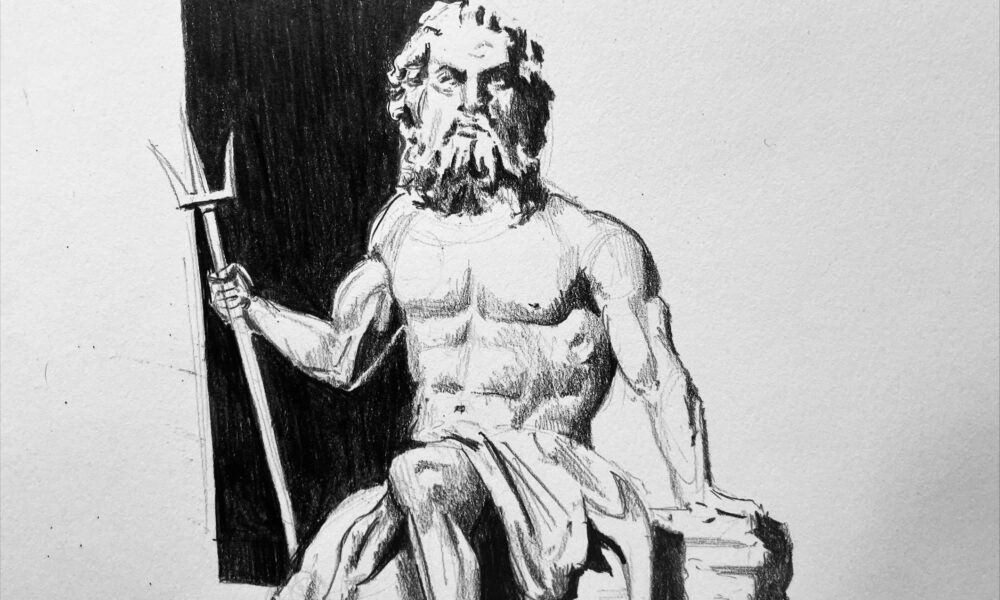

The world of mythology walks the line between fantasy and fact, reflecting our day-to-day experiences through lofty quests and fated prophecies. It is because of this parallel that, for centuries, we have felt so strongly for these characters and recreated them age after age. Where other words might struggle to leave the pages of a book and take flight in imagination, mythology comes alive as if enchanted.

This world of myth and magic followed me through to adulthood, turning my attention towards the Trojan War. My passion for Greek mythology passed from Percy to Patroclus when I read The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller and wept over his tragic heartbreak. I became enraptured with the song “Achilles Come Down” by Gang of Youths, a seven-minute depiction of Achilles’ psychological turmoil, as he’s choked by grief, hovering on a precipice. I was further enticed to read Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, a beautiful blend of prose and poetry in the voices of Trojan War women long forgotten.

The influence of mythology is timeless throughout art, literature, and performance. Everyone in the modern age has consumed traces of mythology, whether they are aware of it or not. So deeply ingrained in pop culture, it’s hard to notice its presence. It is in our common vernacular—Achilles’ heel, playing at Cupid. It’s in brands we use often: Nike, Amazon. Even Mythology-inspired media: If you’re a Swiftie, you’ve probably heard the song “Cassandra,” based on the myth of Cassandra of Troy.

Elizabeth Ellison, Department Head of Classical and World Languages & Individuals and Societies at Elmwood School, gave the example of Finding Nemo in an interview with The Tribune. She often uses this as a gateway to introduce Homer’s Odyssey. Traces of myths exist even in the archetypes that most stories are carved from today, from the oversexualized and underestimated Helen of Troy to the foolhardy and ambitious Achilles.

It is truly singular how mythology has transcended regions and time in this way. But why? Why is it that mythology delights and inspires, centuries after its inception?

Lynn Kozak, associate professor of Classics at McGill University, suggested in an interview with The Tribune that myths allow for immeasurable multiplicity—infinite “fanfictions” reviving the same stories over and over. These core myths are so robust that no matter how many times they are reformed, much like the Ancient Greek monsters, they continue to attract attention. Within this variation, there are numerous gaps to fill and interpret, allowing for the easy proliferation of new stories.

Ellison articulated some additional reasons why myths continue to captivate youth today. For her, the core of these stories is their humanness—and it is what draws us back time and time again. In the words of Homer’s Achilles, “[the gods] envy us because we are mortal, because any moment may be our last. Everything is more beautiful because we are doomed.”

The gods are compelling because they are crafted to be sacred but never rise above human fallibility. Gods, heroes, and monsters alike have become the tropes constantly revisited through culture, their lessons acted out in centuries of art. We cling to them because it allows us to access timeless human elements, to adopt perspectives that provide clarity and connection.

Mythology is accessible not only in its content, but also its form: Storytelling. Ellison shared an anecdote of a time she was stuck on a bus in Athens and decided to share a well-known story to pass the time. Children and adults alike were at the edge of their seats, urging her to go on. Beyond the story itself, sharing it in this form paid homage to how myths were once propagated verbally— a form that, although uncommon, still captivates audiences today. It draws on the human desire for relatedness through imagination by skirting the edges of our reality and touching on the universal struggles and joys that bind us together.

To consume mythology is to look into a mirror that reflects our own world; but that mirror soon becomes a portal to another world entirely.

Ellison also notes that these modern reimaginings foster accessibility for young students, funneling them towards mythological interest. They play on children’s innate curiosity about the world, drawing them past the modern retelling back to history. Kozak seconds this notion, describing these interpretations as “gateway drugs” to discovering the core myths.

Although modern reimaginings can have wonderful effects, there can be a concern about becoming oversimplified in our adaptations— something that Kozak highlighted. They referenced a paper they co-wrote on Miller’s Song of Achilles, mentioning how it was almost too homonormative. Achilles and Patroclus’ romantic relationship was so clearly defined that it lost the relational complexity present in Homer’s Iliad. They intimated that revisions of ancient myths, particularly attempts to highlight silenced voices, can come at the expense of engaging with the aspects of those characters that already exist. Kozak mentions Atwood’s The Penelopiad as an example where the confident intelligence that typified Homer’s Penelope was eclipsed by something more martyr-like.

Despite their flaws, I am eternally grateful for myth reincarnations as they’ve granted me both companionship and knowledge. From Orpheus and Eurydice, I learned to trust in love and oneself; from Daedalus and Icarus, to be mindful of hubris and to moderate ambition; and, of course, Hades and Persephone taught me never to accept pomegranates from shadowy men. All equally valuable morals.

Mythology is a tie that weaves through time and space to bind us. It connects us to history, childhood, and one another. I hope to return to Camp Half-Blood one day, as I know there are infinite adventures to be had and numerous lessons to be learned. But for now, I leave you with the words of Nico di Angelo: “With great power comes… great need to take a nap. Wake me up later.”