Joseph Tisiga’s IBC: Dystopic Autonomy, on display at the Parisian Laundry gallery until Nov. 20, is a complex play on primitivism, where the contemporary meets the mythological in a series of watercolour paintings and un-stretched canvases mounted on AstroTurf. For a portion of the work displayed within the exhibition, Tisiga juxtaposes conventional Western perceptions of First Nations culture with beloved Archie Comics characters, interacting in a way that is reminiscent of a dystopian cross-cultural exchange. Scenes include Jughead sitting beside a first nations chief narrating an unknown tale, Veronica teaching a native woman the nuances of preparing a bowl of cereal, and Archie—excited and shirtless—discovering a fur covered wigwam, or variation on the traditional teepee. There is a sense of intentional timelessness to the paintings, where the boundaries between setting and reality blur in loose and often scrabbled brushstrokes, thus forcing viewers to confront the relationship between past and present, visceral and animated.

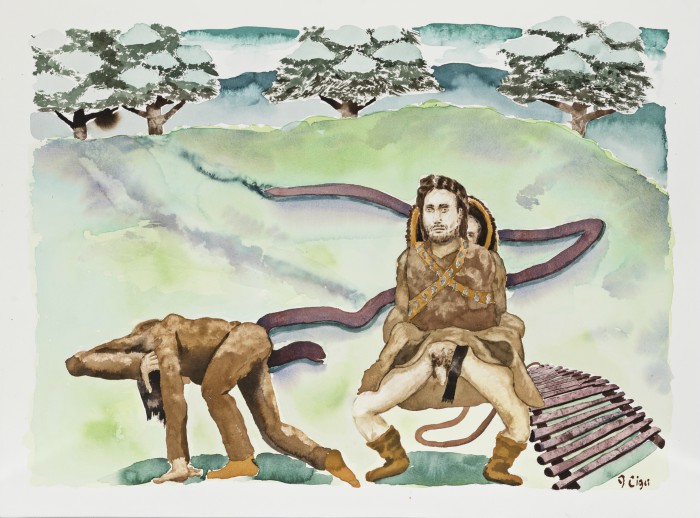

The larger portion of Tisiga’s exhibition is a series of 16 watercolour paintings that describe a personal interpretation of a Kaska folk legend, where a mythological, human-consuming beast is disguised in a collection of urban, and somewhat misleading, objects. It might be lurking in the flaming graffiti in Exercise is Vitalm, or in the ominous striped man come to collect a spiritual tithe in Appears Self Evident. Perhaps the monster resides in the ghoulish scarecrow leering from its post in Trespassers Menaced by Psychosis. Altogether, the paintings present uncomfortable glimpses of human nudity and scenes of impossible context through a heavy-handed use of what is generally considered a delicate medium. The often ambiguous subject matter forces viewers to engage in an interpretive role, where they must make sense of the intricate narrative and open-ended titles while mulling over a glass of wine generously provided by the gallery.

In Anima Animus Paradis explores the role of theatre in the industrial gallery space, using curtains and three-dimensional positioning of his canvases to interact with the viewers, whom Paradis might otherwise call ‘puppeteers.’ His series of eight paintings, accompanied by a rotating sculptural head that encourages continual, circular viewing of the work, depict amorphous and genderless figures. The figures are representationally abstract and painted on colourful backgrounds, encouraging a distorted understanding of depth and texture within their dreamlike quality—others shed any semblance of humanity and instead simply use compositions of line and shape. Displayed in the basement of the gallery, where viewers can access the room through a narrow passageway of exposed brick, the paintings appear tucked away—a forgotten theater for the intrepid to discover in the bowels of the building.

On a more personal note, I found the exhibition provided a unique—albeit somewhat confusing—addition to a Thursday night that might have otherwise been spent huddled over books in the library. I often feel that students view art with the overarching bias that comes with knowing a big name; when one hears Rembrandt and Degas, there is no confusion as to whether or not the painting might be considered ‘good.’ Going into the exhibition without context or an understanding of what I was undertaking presented a blank slate for viewing the paintings and allowed my emotional and visual experience to be completely unique to me as the viewer. Admittedly, many of the paintings were unsettling. But as I walked out the doors of the gallery, I knew that I had come to know that feeling without the aid of museum descriptions or social expectations.