The McCord Museum is showcasing Edward Curtis, an early 20th century photographer, with an exhibit of images from his encyclopedia The North American Indian.

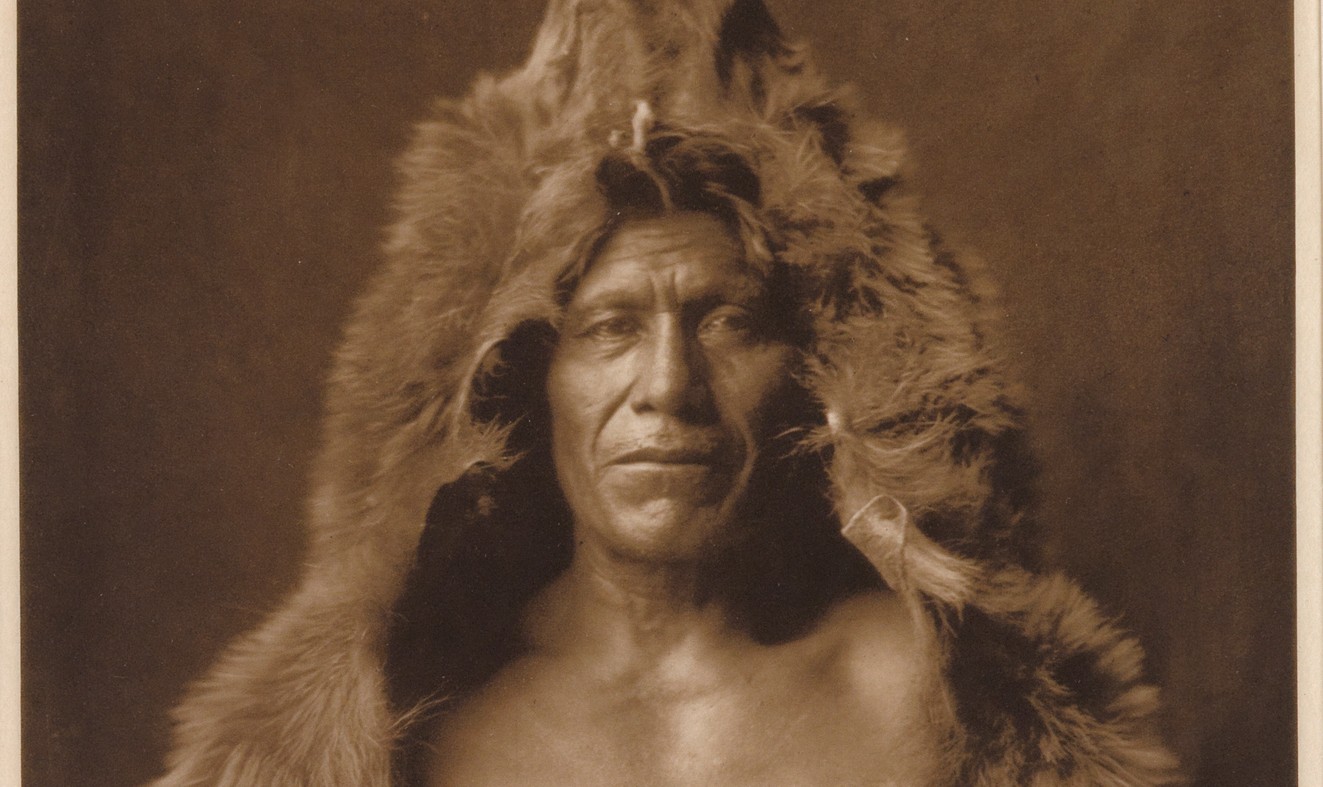

Sepia-hued photographs hang delicately on dark blue walls. Images fill the gallery: a young Mohave girl stares directly into the camera; three Apsaroke horseriders recede into the distance; an Arikara medicine man stands wrapped in his bear skin.

Between 1906 and 1930 Curtis resolved to photograph as many Indigenous peoples of North America as he could, as a way to preserve what was thought of as ‘the vanishing Indian.’ This belief developed from two circumstances: one was the rapid population decline caused by war, slavery, and diseases introduced by European immigration; the other was the program of forced assimilation of Indigenous peoples into mainstream society.

Curtis travelled throughout Canada and the United States, and took approximately 40,000 pictures. Critics pointed out that he staged his photographs to show an idealized vision of Indigenous peoples—for example, by portraying horsemen wearing headdresses into battle when in fact these were only meant to be worn on very rare occasions, and the right to wear one had to be earned. Curtis received additional criticism for editing his shoots so that Western objects, like clocks, were removed from the final print. His motive, however, did not seem exploitative—rather, aim was to show Indigenous peoples in their original environment, as though untouched by European technological or economic influences.

In light of these criticisms, it is interesting to compare Curtis’ work to that of American photographer Timothy O’Sullivan. O’Sullivan is renowned not only for his American Civil War pictures but also for the realism in his images of Indigenous peoples. Instead of shooting portraits of subjects in ceremonial dress, a style that Curtis employed, O’Sullivan instead chose to photograph individuals as they appeared in their everyday life, even if they had a semblance of a Western influence in dress or artifact.

Keeping Timothy O’Sullivan’s work in mind when viewing the McCord exhibit makes for an interesting experience. There is a certain poignancy to the photographs because of Curtis’ naive attempt to sustain the idealized and romantic view of Indigenous peoples in his era.

At the same time, Curtis’ images of Indigenous peoples in their traditional milieu serve as a contrast to the current-day, when Indigenous peoples in cities remain invisible, but stereotypical images of them persist.

McCord’s exhibit is an invaluable opportunity for discussion of societal portrayals of Indigenous peoples, both past and present.

Edward Curtis: Beyond Measure runs until November 18 at the McCord Museum (690 Sherbrooke West.) Student admission $8; free admission every Wednesday from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m.