Faced with the frigid winter winds and 5:00 p.m. sunsets of January in Montreal, spending a Wednesday evening staying in, staying warm, and staving off the mid-week slump may seem inevitable. Yet on Jan. 15, over 250 students and community members braved the elements and gathered in La Sala Rossa to attend the McGill Collective for Gender Equality’s (MCGE) Lilith Fair, a night of live music inspired by the groundbreaking feminist music festival of the same name.

The original Lilith Fair was a watershed moment for women in music. Conceived and helmed by Canadian singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan, the touring summer festival featured a lineup of all-women musicians such as the Indigo Girls, Alanis Morissette, and Tracy Chapman. In doing so, the festival aimed to defy the music industry’s misogynistic tendency to pit women against each other and instead cultivate a supportive community of artists and a concert environment free from sexual harassment.

Critiques of the festival’s ethos were plentiful. Some were merited—the festival’s first lineup was overwhelmingly white—while others were clearly steeped in homophobia and misogyny. Still, Lilith Fair was an unquestionable success; despite only running for three summers between 1997 and 1999, Lilith Fair grossed over $52 million USD.

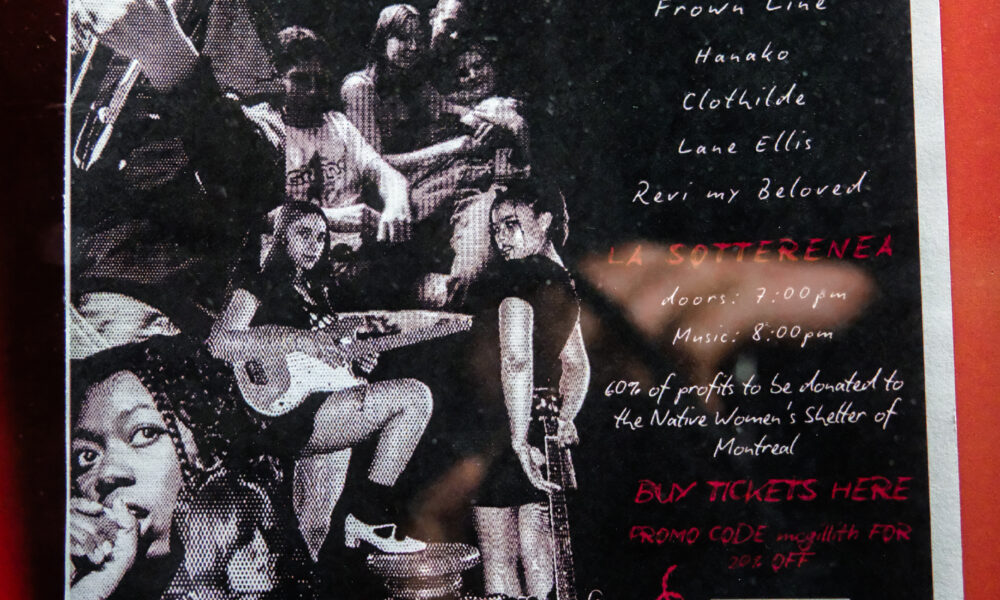

To honour the festival’s legacy, co-organizers Dre Pupovac, U2 Arts, and Alex Leitman, U2 Science, recruited five local acts—Revi my Beloved, Lane Ellis, Clothilde, Hanako, and Frown Line— fronted by women and non-binary artists to co-headline the event. From the audience’s excited buzz, as Pupovac introduced the event, it was clear that Lilith Fair’s mission continues to resonate deeply.

“We’re living in times in which we’re watching as women right across the border are fearing for their reproductive healthcare/education rights and feeling as though they’ve lost control over what happens to their own bodies,” Revi wrote in a message to The Tribune, reflecting on the importance of the festival. “As long as women feel threatened or powerless, creating safe spaces for women will always be important, even if it’s just to listen to rock music.”

The first act saw Revi my Beloved’s driving drum beats and infectious energy set the tone for what was sure to be a wild evening. The audience cheered. The stage lights flashed. Then, the room went dark.

What we would soon discover was a neighbourhood-wide power outage had brought the event to a screeching halt. However, the organizers quickly sprang into action.

“In the moment, I kind of just locked into problem-solving mode, so I didn’t have time to think too much,” explained Pupovac. “It was just, like, okay—what do we do?”

Within minutes, MCGE volunteers had illuminated Lane Ellis with their phone flashlights as the singer performed acoustic versions of her own songs and a stunning rendition of “Linger” by The Cranberries. The organizers then invited anyone who wanted to hop onstage and sing to do so, leading to an impromptu singalong until they announced the event’s postponement.

Eager to host Lilith Fair as intended and allow the remaining acts the chance to perform, the organizers worked tirelessly to reschedule, and just four days later, the event was back up and running. Despite the slightly lower turnout, audiences were just as enthusiastic, if not more, the second time around. Ellis’ airy tones and introspective lyrics had lent themselves well to a stripped-back performance, but hearing her songs as intended provoked raucous cheers from the crowd. By contrast, Hanako’s, U2 Arts, blend of folk and dream pop left the room in a reverent hush. Lilith Fair officially wrapped up just after midnight, leaving a tired, beaming crowd to disperse into the chilly night, chatting about when the next Lilith Fair might be.

“If [women and other marginalized groups] want safe spaces, […] no one’s gonna do it for us,” Avery Albert, a community member who came out to support both versions of the event, reflected. “We really have to cultivate those spaces [ourselves].”