On Feb. 3, Chriscinda Henry, one of McGill’s associate professors of art history, delivered a lecture for The Courtauld Gallery’s online speaker series on Concert Champêtre, a famous painting by Venetian Renaissance painter Titian. Henry exposed how Concert Champêtre, the title of which translates to “pastoral concert,” offers a window into how the elite youth in Renaissance Italy chose to spend their leisure time.

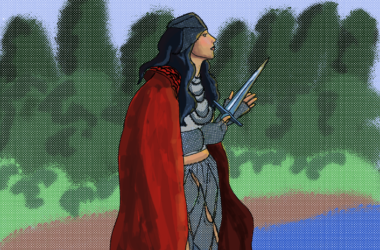

Painted between 1509 and 1511, Concert Champêtre depicts a young man adorned in a lavish red outfit, playing his lute alongside a more simply dressed man and two semi-naked women. Although seemingly at ease, several qualities hint that the youth in the painting does not belong. Besides his clothing, his elaborate instrument is grand compared to the simple pipe that one of the women holds, suggesting his capability to create complex music compared to her simple tunes. Henry attributes his out-of-place persona to some art historians’ assumptions that the lutenist was a real, yet unidentified patron who commissioned Titian to insert his image into the pastoral scene. This artistic self-insertion was popular among the elite in the 16th century as a form of informal self-representation.

“In the homes of certain Venetians, who might be considered as a cultural avant-garde, novel forms of intellectual exchange, music-making, theatrical performance, and collecting came to articulate a new mode of poetic self-fashioning and generational distinction on the part of young Venetian patrons,” Henry said. “The shepherd maschera, or persona, […] provided the ideal vehicle for a liberating poetic form of self-expression steeped in classical literary and theatrical culture.”

While he is participating in an artistic movement celebrating self-expression and leisure, the patrician’s outfit clearly boasts his high position in the Venetian political society. Henry noted that the youth wears Compagnie della Calza attire, identified by his cloak and subtly striped hose. The group, called “Company of the Hose” in English, was a fraternal youth society that collected and refined the sons of Venetian elite by having them host lavish spectacles for the public. The company included several different groups, all of whom sported distinguished colour combinations of hose. The youth in Concert Champêtre wears a white and grayish-green striped hose on his right leg and rose-coloured hose on the left—which is hidden in the painting—representing the so-called “happiness group.” This group prioritized the reciprocal exchange of friendship among guests and fellow patricians alike.

The painting itself features the homosocial—or, as Henry argues, potentially homoerotic—friendship between the central youth and his pastoral companion, showing that the friendship has transcended beyond elite status. However, Henry argued that the similar body positioning between the urban elitist and pastoral shepherd reflects a sense of alter-ego. Therefore, Concert Champêtre reflects both the youth’s pride in his political status and the equal passion he feels for simple, pastoral life.

“[There is an] intimate gesture of homosocial fellowship, almost fusion, between the two young men seated at the center of the composition—the elegant compagno, and his rustic shepherd counterpart,” Henry said.

Although Venetian elite were free to live joyously and abundantly in their youth, their powerful parents expected them to renounce these luxuries and take on a more serious and political role upon reaching adulthood. In 1509, the youth had to abandon their lifestyle due to the War of Cambrai, instigated by a European alliance led by Pope Julius II and Louis XII of France, who aimed to disassemble the Republic of Venice. At that time, the Venetian government forbade all festivities and colourful hose to facilitate focus on war planning. Although the war ended in 1511—once again permitting festivities—the previous generation of elite youth had become Fausti, meaning soldiers, outgrowing the carefree privileges of their adolescence. Henry acknowledged that the pastoral theme of Concert Champêtre represents the generational nostalgia for both a simpler rustic life without war and for an adolescence celebrating life and art.

“If one of the young men of the Fausti had proved to be not only the central subject, but also the patron of the Concert Champêtre, this prompts questions about the painting, as a work that captures and commemorates for posterity, a brief and liminal stage of life that was already nearing its end for the Fausti by 1509, when the painting was likely commissioned and begun.”