On Mar. 10, Roy Ellenwood, a retired professor from York University and translator of Québécois literature, presented “Riopelle and Indigenous Art: The French Connection,” an online lecture with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA). The presentation, which complemented the exhibit Riopelle: The Call of Northern Landscapes and Indigenous Cultures, elucidated the artwork’s historical and multicultural contexts.

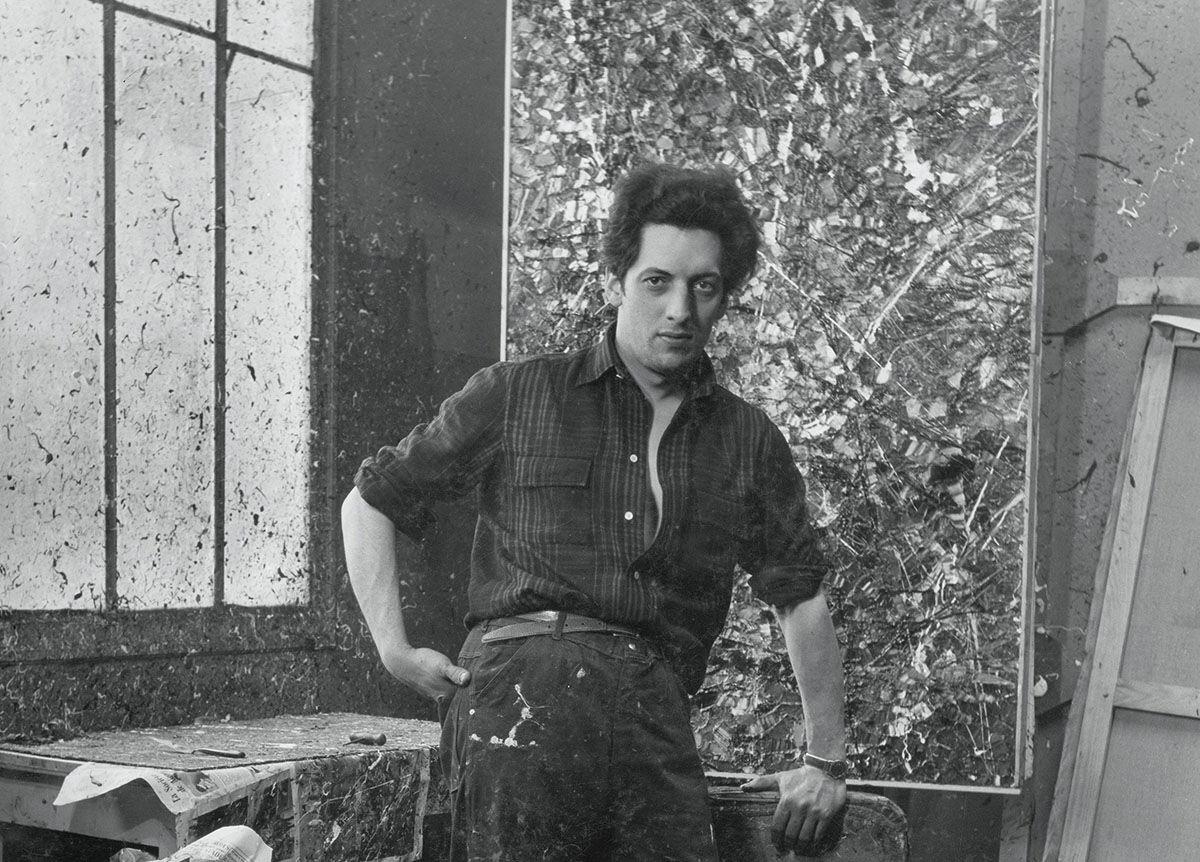

Until Sept. 12, 2021, the MMFA will feature a major in-person and virtual exhibition dedicated to one of Quebec’s most renowned artists, Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923-2002). Riopelle showcases over one hundred of the artist’s works, juxtaposing them with their sources of inspiration—Indigenous artworks, artifacts, and anthropological documents. By displaying Riopelle’s art adjacent to its inspirations, the exhibit connects his fascination with Indigenous art to his work.

The exhibit’s free virtual tour shows hundreds of Riopelle’s works alongside Inuit masks, sculptures, tools, and other objects that tell the story of their creation. One room, Icebergs, features walls covered in monolithic, white canvas paintings. A sculpture looms in the room’s center, alongside a case displaying Inuit tools, carvings, and postcards from Riopelle’s trips to the Arctic. The concomitant placement of Riopelle’s art with Inuit art and history demonstrates their correlative existence in Riopelle’s artistic processes.

“It was in 1955 that Riopelle first began to make reference in his titles to the masks and sculptures of [Indigenous] artists of the Canadian Arctic and West Coast,” Ellenwood said. “These three paintings, in spite of their significant titles, are not representational [of Indigenous art] in the usual sense of the word [….] Without their titles, they would be hard to distinguish from other abstract works on paper of the same period. The point is that these paintings do not depict masks, they respond to them.”

Although Riopelle’s paintings do not exhibit visual similitude to Indigenous sculptures, masks, or carvings, they express Riopelle’s feelings upon viewing them. Ellenwood then explored the circumstances that fostered Riopelle’s fascination with and eventual exploration of Indigenous visual cultures, and how they became part of his artistic process. During and after World War II, Riopelle’s interactions with figures of the surrealist art movement, such as French art critic Georges Duthuit, inspired his craft.

“Since the 1920s, the surrealist movement had been publishing articles on and photographs of Indigenous art, arguing that it deserved to be seen as more than mere anthropological evidence,” Ellenwood said. “[They argued] that it was great art in its own right, representing an alternative to the impoverishment of European culture, a possibility of renewal in times badly in need of what they called ‘a new myth.’”

Ellenwood’s presentation offered a small, representative glimpse of the art exhibit’s featured works, with oil paintings and lithograph prints that exemplified how Indigenous cultures influenced Riopelle’s creations. Many pieces, such as Tyuk, featured string-like patterns that referenced Inuit string figures and games which were popular across the Arctic.

“Inspired by the Inuit game of making shapes by manipulating a loop of string around the fingers of both hands, [Tyuk] refers to the sound that was traditionally made by the manipulator of the string as the knots, each representing a bird, were pulled, one-by-one, and came apart, representing the bird flying away,” Ellenwood said.

Other interesting pieces of information in the exhibit included letters sent from Riopelle to his companion, Joan Mitchell, and photos and postcards from Riopelle’s excursions to the High North. Ellenwood explained how Riopelle’s personal life, including his hobbies and relationships, was inseparable from his artistic activities and persona.

“His excursions included several to Pangnirtung on Baffin Island, one of which occurred in the summer of 1977,” Ellenwood said. “During that trip, he sent a half-dozen postcards to Joan Mitchell in France, keeping in mind that she did not appreciate his new Quebec residence, and as an animal lover, hated his enthusiasm for hunting and fishing. It is hard not to read some of these notes on these cards as teasing gibes.”