McGill’s Department of Art History and Communication Studies welcomed Carmen Robertson to present her research on the artist Norval Morrisseau on Nov. 14. The event was the latest in a series of lectures hosted by the department which aim to provide opportunities for discussion on current research in the field of art history.

Robertson, a Scottish-Lakota professor of art history at Carleton University, took questions on her archival research on Morrisseau’s work. Her work examines Morriseau’s relationship with art dealers during the 1960s, when he first emerged into the Canadian and international art scene.

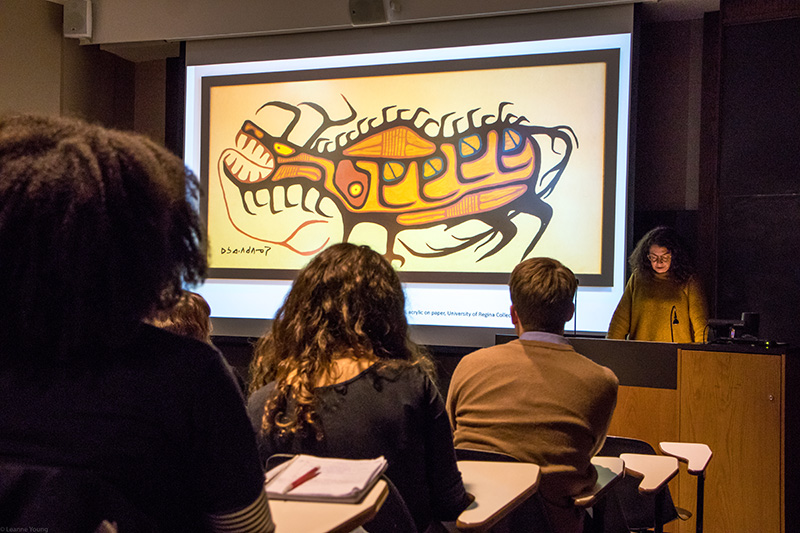

Robertson sees Morrisseau as the grandfather of contemporary Indigenous art. He initially rose to prominence in Toronto and Montreal in the 1960s. Born in 1931, the Anishinaabe artist grew up in the Sand Point reserve in Ontario, learning the stories and traditions of his people from his grandfather—many of which would become the subjects of his paintings.

Curated by Jack Pollack, Morrisseau’s first gallery exhibit took place in Toronto in 1962. Before this landmark exhibit, most Indigenous artwork shown in Canadian galleries was by Inuit artists. However, Morrisseau’s first show was such a success that all of the paintings sold on the first day it was open. Later in the decade, Montreal’s Expo 67 commissioned a mural from him, and Morrisseau continued to gain international recognition with the help of art dealer Herbert T. Schwarz.

Robertson’s ongoing research on this period started with a donation from the archival sources of the Art Gallery of Ontario. She did, however, note that while she relies on these sources for her research, this archival approach is problematic for studying Indigenous art. Archives overrepresent written records, while much of Indigenous cultures, histories, and traditional knowledge are passed down orally.

“[Morrisseau’s] life and art demand engagement outside of conventional art discourse,” Robertson said.

He learned many stories and traditional knowledge from his grandfather, but was also forced to attend residential school at a young age. As opposed to the extensive archives of traditional western painters, much of Morrisseau’s life, influences, and education is missing from the writings and materials in an archive.

“Methods of research require academic unlearning in order to make space for Indigeous ways of being and knowing,” Robertson noted. “Morrisseau’s art did not follow traditional trajectories.”

Robertson’s research draws on writings from Pollock and Schwarz that documented Morrisseau’s entrance into the gallery scene. By analyzing the relationship between the artist and the dealers, she found benefits and problems alike associated with the negotiation between the two parties. While Schwarz and Pollock brought Morrisseau’s art to a broader audience, they were exploitative and verbally abusive toward him. Robertson concluded her talk by addressing the need for Morrisseau’s unmediated voice to be preserved—the archive only shows the artist from the problematic perspective of non-Native art collectors, not from the artist’s own experiences.

The lecture attracted an audience of both McGill students and members of the public. McGill art history professor Angela Vanhaelen organized the lecture series and invited Robertson to share her traditional archival perspective on a contemporary Indigenous artist—an uncommon approach within the Canadian art world.

“It’s always interesting to hear about [researchers’] processes and their work in progress, because if they read something they’ve already [finished], it’s not quite as open-ended and you can’t ask as many questions,” Vanhaelen said.

The department will continue its lecture series with Finnish media scholar Susanna Paasonen on January 23.

Respectfully, as an Indigenous Artist and Curator – research into Norval’s legacy and/or in this case “challenge and abuse” by peers, let’s say – is, yes – very problematic and/or disparate – in that the perspective and research is constrained to a non-Indigenous person and the history, syllabus, story-telling honestly as it pertains to sacred depiction, symbolism, and meaning, literally with a curve or colour or sway of subject or sky/water scape in situ is of historic reach and meaning. I am a Sixties Scoop Survivor, apprehended as a carryover, being that my Mother, Aunties were victims of the residential school horror – as referenced in your article. I proffer that it is actually very – incredibly problematic – for those of us of our Culture – this rich Culture, that bespeaks Canada – that researching the “art” of a very iconic Indigenous Artist is now, in late 2019, declared problematic – being that, well, interestingly, Indigenous culture – which imo imparts to the western world label as “art” is so involved and is primarily historically handed down orally. Well. yes. Absolutely. That is only problematic for those who are not of our culture or in research did not drill down further to that core, passage and expression of our proud Peoples – for thousands of years. The problem in fact is that that sacred passage across many tribes, syllabus and Nations – is not archived or translated or scribed for easy or accessible research, perhaps? The expression, modem and art in this case garners further research in testament to honor its historical place and reverence in the world of art and culture today, since

First Contact imo. Respectfully, I submit above in response to this article posted about my Peoples, and of a revered icon/elder, and to proffer mere commentary as to the problematic mystery that has non-Indigenous research full-stop for this realm of cultural / art expression of a very distinct, and indigenous to these lands for thousands of years, class of Peoples.