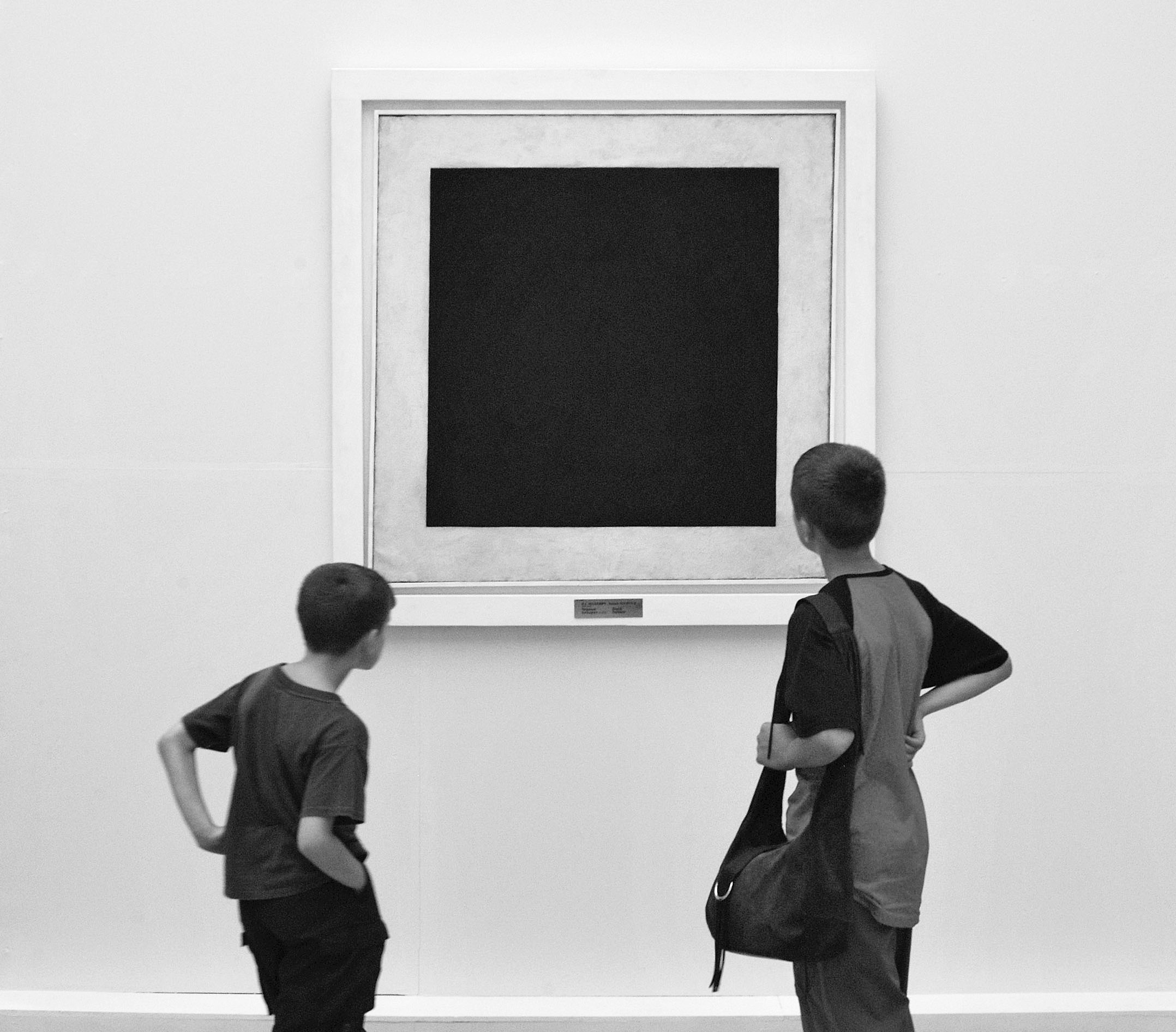

In my youth, I would occasionally visit the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. For the uninitiated, the Tretyakov houses a vast collection of Russian fine art—picture the MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Frick collection all diced up and served as an exquisite borscht. I can’t remember much of what I saw, but I clearly recall Malevich’s “Black Square” on display. What gives, Tretyakov? All your other pieces at least depicted something; in some way, they spoke to the viewer, and required some permutation of skill and effort. This was a black square. If I could paint a black square by my tender seven years (my bedroom wall was adorned with a number of Blinderman originals, at least half of which could be deciphered as animals, humans, and—after one particularly inspiring trip to a museum—a reproduction of the armless Venus de Milo), why wasn’t my work considered fine art? I was outraged; as we say in Australia, this was just not cricket.

In my indignation, I sought answers from my elders, but nothing satisfactory emerged. I accepted the “Black Square” as most people accept the majority of recent modern and contemporary art—something too esoteric and abstract for mere mortals to understand.

Since that experience, I’ve approached art with a generous disposition—but it’s time to draw the line. Open mind? Sure. Provocative subject matter as social critique? Yeah, I guess. Dropping condoms, pantyhose, and liquor bottles on a mattress and calling it “My Bed” (I’m looking at you, award-winning artist Tracey Emin)? Nope. Now we’re just rehashing The Emperor’s New Clothes with Warhol prints. We’ve gotten to the point where something stupid and obnoxiously mundane is lauded simply for being inflammatory (Ms. Emin, who likes to have sex and drink, communicates her insights with all the subtlety of Girls Gone Wild).

To put it bluntly: what’s my beef with contemporary art (if I were an artist, I could communicate this to you by shaping beef mince into the word “art” and serving it at my gallery/kitchen/multipurpose installation space)? Much of what’s praised is abstract and conceptual, and is glorified for possessing depth that—let’s face it—we’re simply afraid to say it lacks. Otherwise (although these categories often overlap), whatever’s produced seems so devoid of skill that even I can claim authorship. In spite of my earlier braggadocio, I’ve made minimum headway in terms of artistic ability; if my skills are sufficient (barring an incredible investment of time and training), I can’t help but fail to be impressed. The result of all this conceptually-oriented produce is that language has had to pick up the slack, leading artists and critics alike to wax grandiloquent on the artistic merits of “negative space” and other equally inane ideas.

If we assume that the abstract and mundane are valid forms of art, and remove the necessity for technical skill to boot, we preclude the need for art to be located in galleries. In fact, we can do away with artists—their craft, in the form of the everyday, the ordinary, and the crude, is to be found all around us. Why don’t we take the democratizing logic of “art from anything, by anyone” to its natural conclusion, and admit that such assumptions would mean that the need for professional art is undone by its very essence? Tracey Emin’s made her bed—let her lie down in it.

This is terribly written and makes no contribution to society, frankly.

I think that makes it art