Despite the self-isolation imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, I’ve still been dolling myself up to go out on the weekends and even, recklessly, the weeknights. With bars and venues closed and our lives re-oriented from being mostly online to almost entirely online, it’s unsurprising that people have been flocking to online ‘clubs’ to continue one of life’s simplest, but most rewarding pleasures: Dancing. Besides the sheer fun of it all, the emergence of online dance parties provides a vital space for queer and marginalized peoples to foster community in these seemingly disparate times.

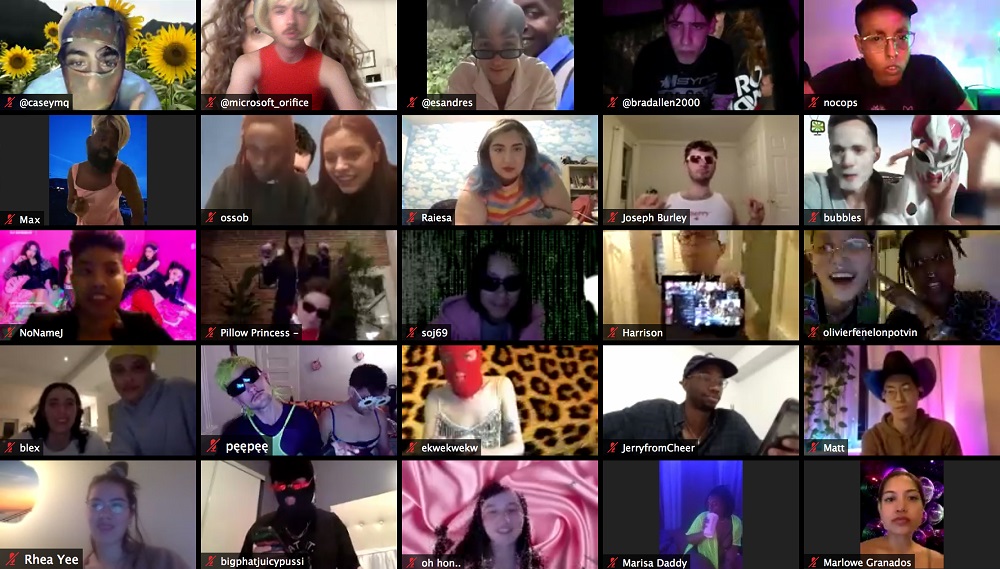

Club Quarantine (Club Q), not to be confused with D-Nice’s Instagram live event, is the most high-profile of these online queer clubs, having featured DJ sets by big names like Charli XCX, Tinashe, and Dorian Electra. Created as a joke between four friends in Toronto, Casey MQ (Manierka-Qualie), Brad Allen, Ceréna, and Mingus New, Club Q now broadcasts every night on Zoom, creating a sense of familiarity amongst its patrons.

“We have Club Q regulars now,” Manierka-Quaile, DJ and co-founder said in an interview with The McGill Tribune. “There [are] some dedicated people [who] come all the time, and that is beautiful to see. This is the space that [they now] go to. ‘What am I doing tonight? I have nothing to do. I’m definitely going to Club Q.’”

Online dance parties operate in a similar fashion, as Zoom’s audio- and screen-sharing functions allow producers to highlight acts and patrons. The chat function allows users to talk openly and message each other privately, mimicking the chaos of bumping into people in a real club. In all, Zoom’s tools give producers the same artistic and logistical oversight as they would over an IRL venue. A highlight of Zoom is the ‘spotlight’ tool, where hosts choose a screen to share on an online ‘jumbotron.’

“It’s kind of become the heartbeat of Club Q, because everyone gets to have their moment,” Ceréna, artist and co-founder said. “Here, because we’re all at home, you can do anything you want! We can be spotlighting someone cooking in the kitchen or someone giving us a full twerk moment or someone with their pet turtle.”

These features can be further used to elevate a traditional club experience, allowing for more experimental camera angles and perspectives. Avery Burrow, co-founder of Montreal’s Vice Versa Productions, recently held Queerantine, a Zoom version of their lesbian party, Blush, geared towards raising funds via PayPal to support QTBIPOC sex workers who have difficulty directly accessing government aid. Burrow noted the benefits of using go-go dancers and backgrounds to create a cohesive visual experience on Zoom. Besides providing financial support, Burrow sees Queerantine’s positive role extending beyond its patronage.

“Just [in] advertising for Queerantine, I got a lot of responses from people being like ‘Oh, it’s just so nice to have something in my feed that’s positive right now,’” Burrow said. “That’s what we’re trying to do is break up the negativity and […] build community.”

Like any real club, however, unwanted patrons can appear, in this case in the form of online trolls. Hosts must take it upon themselves to moderate chats and kick out users when it jeopardizes the safety of other patrons. Burrow kept the password to Queerantine locked to the organizers and those who donated to the event’s GoFundMe; though not a foolproof method, it did reduce the chance of homophobes crashing the party.

Showing solidarity with these spaces is more vital than ever, with queer and marginalized people disproportionately affected by lay-offs and financial strains of the COVID-19 pandemic. But, communities have thrived online far prior to the quarantine age, and that may be why so many people who grew up on the margins of society feel at home in these spaces. Manierka-Quaile noted that the re-emergence of queer internet culture has spurned a sort of nostalgia for those who’ve already spent hours lurking in online chat rooms like Omegle and Chatroulette. Now, like it or not, more groups of people are seeking belonging in these virtual worlds.

“This is like my childhood. I think that’s why, for all of us, it was just very natural to […] go onto this platform, because it [had] very chatroom vibes,” Ceréna said. “It’s just kind of wild that when the world stopped and everything just took a pause, [….] I was ready to just retreat and hibernate, [and then] this happened and now it’s like, “Oh shit, we did break the internet!”

A perhaps-unintended consequence of these parties is the absence of physical barriers to accessibility. Clubs and bars are traditionally seen as one of the few safe spaces for queer and trans communities, but have long been inaccessible to differently abled patrons.

“We can bring the dance party to people’s living rooms,” Burrow said. “If you live in a wheelchair-accessible house, that means [that] the dance party is now wheelchair accessible [….] My party can now welcome people who want to be at it, no matter what barriers they might face.”

Furthermore, these online clubs provide a space for people who are unable to see any other queer people in person. Sitting alone in front of a laptop, watching other queers vogue, dance or even just lounge about and drink wine can comfort patrons and remind them that they aren’t alone in their experiences.

“We just needed another outlet for us to be free and to feel […] that sense of community [with] each other,” Ceréna said. “What’s been the most beautiful of Club Q is seeing all the beautiful queer people. I’m in a small town [right now] with no queer people, and this is just like, serving me. This is making my life just so much better.”

For the foreseeable future, people will have to go online to find these spaces. Club Q shows no signs of slowing down, and Burrows hopes for Vice Versa to host more online parties in the future. Similar parties are popping up: Club Hunhouse for queer women, trans and non-binary people, and STRAPPED.TO, which centers QTBIPOC, is hosting virtual events. When and once COVID-19 passes, these places will likely move into the physical world, however at their core, they remain a uniquely virtual phenomenon. In bridging these geographical and physical gaps to connect queer communities, online clubs will retain an almost ephemeral existence that a physical club simply can not attain.

“In this moment in the quarantine age, you’re going to have to find that community online or you’re going to have to find it within yourself,” Manierka-Quaile said. “By being online, there’s that accessibility to just being tapped in.”

To provide financial support:

Club Q: https://www.paypal.com/paypalme2/reachclubq

Vice Versa Productions: [email protected] or https://www.gofundme.com/f/vf6y9-queerantine-a-queer-online-dance-party

Also Cool Artists Fund: https://ca.gofundme.com/f/also-cool-artist-fund