“Do you want to like the artists you study?”

That was the question posed on the first day of class by the professor who teaches my T.S. Eliot course. He went on to explain that those who weren’t already familiar with Eliot would almost certainly find it impossible to like him after becoming acquainted with the facts of his life. In addition to being one of the preeminent literary minds of his generation, Eliot displayed public anti-Semitism and had a reputation for being a generally unpleasant person. For me, the warning was another reminder of something I already knew: we’re not obliged to admire the artists responsible for the art we admire.

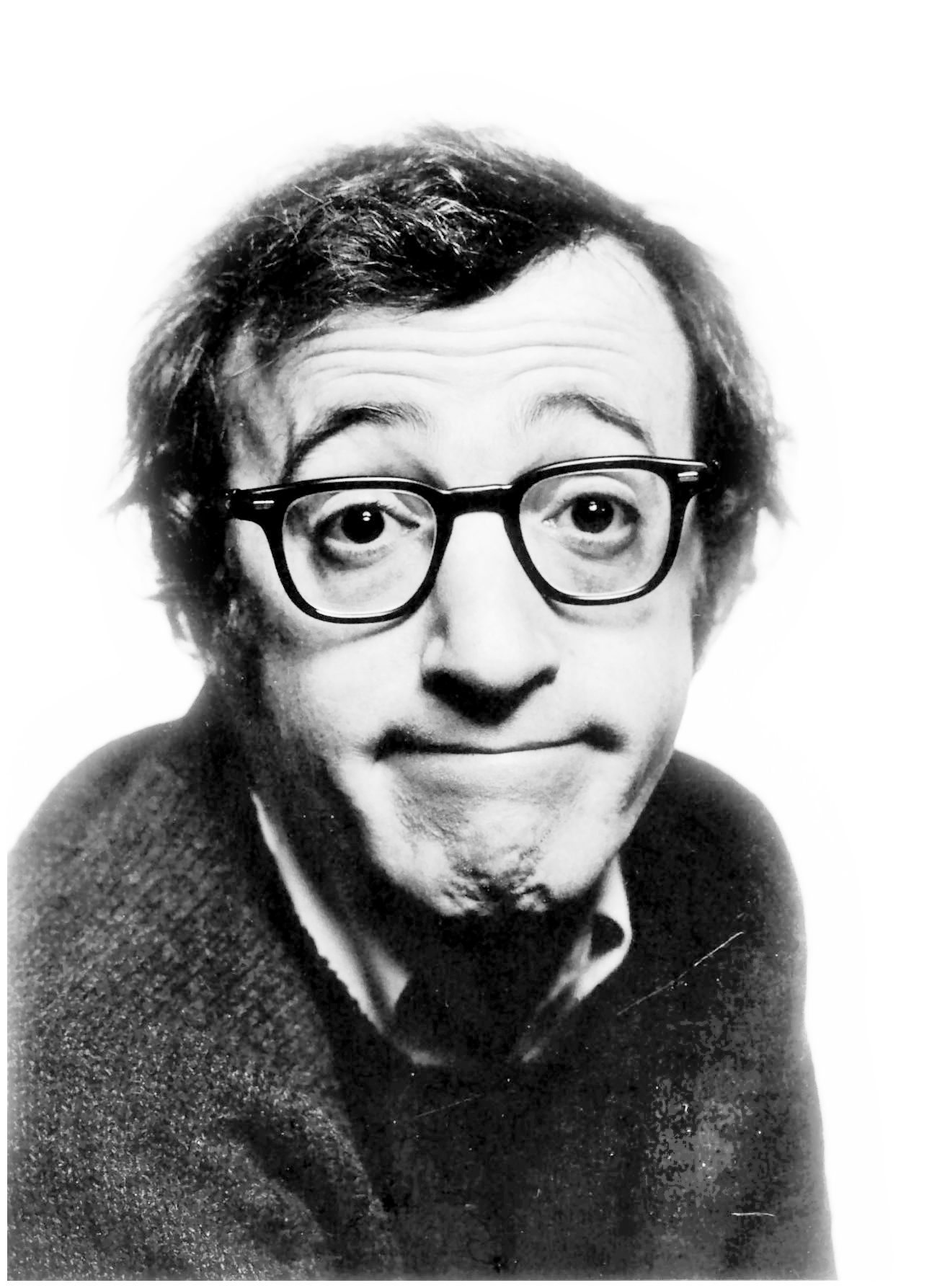

The weekend following that class, Woody Allen was honoured with a lifetime achievement award at this year’s Golden Globes ceremony. In the wake of that presentation, there’s been a heavy stream of discussion concerning the moral justification for giving the award to Allen despite the accusations of sexual assault that were brought against him by his adopted daughter, Dylan Farrow—for which there wasn’t enough evidence to convict Allen with when an investiagtion was conducted by the state of Connecticut 21 years ago.

Farrow herself has been largely responsible for the renewed attention towards the situation. After opening up about her feelings in a Vanity Fair piece published last November, she’s continued to share her side of the story with the media in light of Allen’s Golden Globe award. On Feb. 1, Farrow published an open letter in The New York Times detailing her grievances and ongoing struggle. The notoriously private Allen responded last Friday with an op-ed of his own in the same newspaper, denying her claims and promising that the article would be his final public comment on the matter. Later that day, Farrow released another accusatory response through a spokesperson, vowing at its conclusion, “I won’t let the truth be buried and I won’t be silenced.”

The entire saga is disheartening; the resurfacing speculation casts a dark shadow over Allen’s public image, regardless of whether or not Farrow’s accusations are true. However, the larger question that it begs us to ask ourselves is essentially the same one that my professor put forth to his class: How should we feel about an artist’s work when we’re offended by their behaviour? Although there’s a temptation to want to scorn everything they’ve produced, appreciating their art doesn’t have to be seen as a validation of their actions or views.

The connection between an artist and their work is so strong that it’s often easy to forget that a separation can exist between the two. For example, when we read a piece of poetry that isn’t distinctly marked as being the thoughts of a character, our gut reaction is to experience it as if the poet were speaking directly to us—which they are in many cases. But the possibility also exists that the voice we’re hearing is that of a subtle persona developed by its author, which they may want us to view ironically rather than sympathetically. But ultimately, there’s still a connection between an artist and their craft that makes us wonder just how much the latter is a reflection of the former.

Because of this inherent bond, we come to grow attached to artists based on what they’ve produced. Especially in a visual medium like TV or film where an actor can make a name for themselves with a signature role, it’s hard to imagine aspects of their personality not matching up with their on-screen counterparts—like when Michael Richards, who portrayed Seinfeld’s happy-go-lucky Cosmo Kramer, went on a racist tangent while performing a comedy set at the Laugh Factory in 2006.

In Farrow’s open letter, she begins by asking her reader, “What’s your favourite Woody Allen movie?” and closes the piece by assertively rephrasing the question into “Now, what’s your favourite Woody Allen movie?” in an attempt to make us feel guilty for enjoying any of his work. I sympathize with Farrow for the plight she’s had to endure all these years—because no matter the truth behind the events, she’s suffered greatly—but I can’t say that it will change the way that I feel about any of Allen’s films.

That’s not to say that if Farrow’s allegations were true, I wouldn’t disapprove of Allen—I would think considerably less of him as a person. But knowing the uncomfortable truths of an artist’s personal life isn’t an excuse to boycott everything they have produced.

Long before I knew of T.S. Eliot’s racist inclinations, I had read “The Waste Land” and “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and was absolutely captivated by their messages and the scope of their composition. Knowing what I know now, I still consider them to be some of the most impressive works of literature I’ve ever read. Eliot on the other hand? I respect his genius but pity him for whatever unnecessary hatred was inside of him.

It’s ideal when an artist can represent the same greatness as their art; but when they don’t, it doesn’t mean we have to shut our eyes to their work—we just have to view the artist through a harsher lens.

http://www.theonion.com/articles/boy-ive-really-put-you-in-a-tough-spot-havent-i,34949/